In the last few years non-smoking ordinances have spread like wildfire. California has banned smoking in all indoor workplaces, and select cities including Boulder, Colo. and Mesa, Ariz. have followed suit. Even New York City forbids smoking in restaurants. Shamed by public-service announcements and abandoned to their addiction by tough-love family members, smokers have passively moved from office lounges and bars to wind-swept street corners and rainy entrance ways. Standing outside in the winter cold with a nicotine-addled immune system and a rebel posture, it’s easy to feel no one cares about you. But someone does.

Brown and Williamson Tobacco Corp. cares. This Valentine’s day, the company behind Lucky Strike, Kool, and the seemingly uncorporate GPC (generic packaged cigarettes), had their “Strike Patrol” give out single-rose Valentines to workers on smoke breaks, men and women who can’t settle for second-hand cool. Several thousand roses were given in total, to workers in San Francisco, New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, and Philadelphia. Each rose came adorned with a card featuring a heart-shaped variation of the Lucky Strike logo and the words, “Lucky loves you.”

The amorous approach is nothing new for B&W. Last fall, the message at their 1-800 number told callers, “We, Brown & Williamson Tobacco Corp., are in love with you … We’re a giant tobacco corporation and you make us feel like a little kitten. Thank you, lover.”

Steve Kottak, B&W’s manager of public affairs, says the Strike Force hopes to get across to consumers that, “Lucky Strike is there for them … we understand their situation.” Previous actions by the Strike Force have included bringing hot coffee to streetside smokers in New York and Chicago business districts, and providing free phone calls via cell phone to snow-delayed travelers at major airports.

These new marketing practices exemplify Big Tobacco’s resiliency. Last April the prohibition on any advertising accessible by children took effect in 46 states. At first glance, that settlement appeared the first nail in the industry’s coffin because it banned the use of billboards, movie product placements, and advertisements in magazines which have any significant youth readership. Instead, new “direct-approach” advertising methods like the “Strike Patrol” have quickly appeared in the settlement’s wake.

Other examples of direct-approach advertising by B&W have included customized Mardi Gras cigarette packages sold in New Orleans during the festival, and specially published consumer magazines. Such industry-generated magazines don’t look like catalogs or promotional devices, but rather resemble mainstream magazines — although they are covert advertising vehicles for tobacco products, and are mailed directly, free of charge, to anyone on the company’s list of consumers. While both Phillip Morris, with its mag called Unlimited and R.J. Reynolds with CML: The Camel Quaterly publish a magazine apiece, B&W tops the list with three — Simple Living, Flair, and Real Edge.

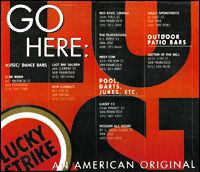

These campaigns’ broad scope combined with personalized focus usher in a new era of advertising, one more akin to political baby kissing than traditional product pushing. Corporate magazines demonstrate a company’s desire to climb into our homes, shape our media and determine knowledge, but I find the roses more disquieting. Can I really trust romantic overtures made by a corporation? Another Lucky Strike advertisement hints at one possible motivation. An ad containing listings of (often covertly smoking-friendly) bar and clubs in local areas runs nationwide in alternative weeklies. In the background — almost subliminally — appear the first two letters in each of the logo’s names oversized so that they spell out: L-U-S-T:

|