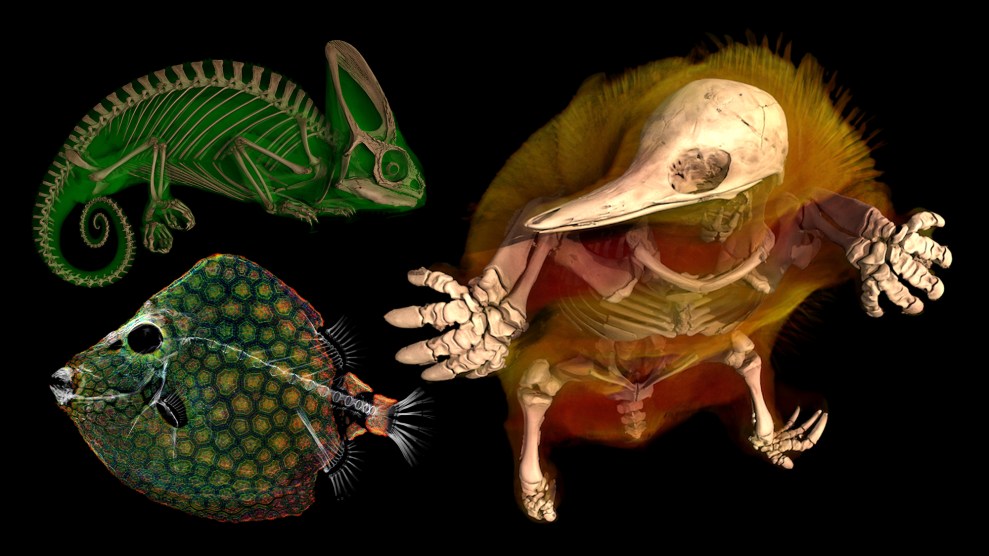

Illustration: Thomas Fuchs

“The government of the United States is not in any sense founded on the Christian Religion.”

THOSE WORDS, PENNED IN ARTICLE 11 of the 1797 Treaty of Tripoli, are as succinct a statement as we have from the Founding Fathers on the role of religion in our government. Their authorship is ascribed variously to George Washington, under whom the treaty was negotiated, or to John Adams, under whom it took effect, or sometimes to Joel Barlow, U.S. consul to Algiers, friend of Thomas Jefferson and Thomas Paine, and himself no stranger to the religious ferment of the era, having served as a chaplain in the Revolutionary Army. But the validity of the document transcends its authorship for a simple reason: it was ratified. It was debated in the U.S. Senate and signed into law by President Adams without a breath of controversy or complaint concerning its secular language, and so stands today as an official description of the founders’ intent.

And it wouldn’t stand a chance in the government of the country we’ve become.

The idea of America was always informed by the ideals of its religious citizens, expressed, often, in religious terms. But the genius of America was the establishment, by those same individuals, of the world’s first secular government. That government wasn’t at odds with religion—even the separation of church and state might be construed as a policy extension of Jesus’ admonition not to pray as the hypocrites do, in public. And many religious factions (among them the 19th-century evangelicals) lobbied for secular governance, to protect themselves from the tyranny of mainstream denominations. Yet some among the faithful, uncomfortable with America from the start, saw secularism as the nation’s fatal flaw, instead of its core strength, and have fought to transform the United States into an expressly Judeo-Christian nation.

Recently, the inheritors of this viewpoint are prevailing. The measure of religion’s intrusion into our government and politics can be found whenever the White House markets a Supreme Court candidate by flaunting her religious convictions and church affiliation, whenever liberal Democrat politicians ostentatiously genuflect to show they can be prayerful, too, whenever a FEMA website directs the public to contribute its hurricane-relief funds to a right-wing ministry. Kansas senator Sam Brownback, gearing up to run for president on a faith-based, antiabortion platform, calls the role of religion in government “the great debate of our season.”

The religious right didn’t come by this prominence by accident, by casually capturing (and capitalizing on) the desire of many Americans for a more meaningful and spiritual life, nor even by the simple tactic of wrapping itself in the purloined flag of the founders and in a misconstrued Constitution. They organized, crafting a far-flung and intricate network of political pulpits, media outlets, funding organs and think tanks, and integrating it into the political machinery of the Republican right. The religious right shares the conservatives’ will to power and also, more than previously, a conviction that it is obligated by destiny to remake the country in its image.

This issue of Mother Jones is dedicated to illuminating the interplay between conservative Christianity and the U.S. government. We regard the movement’s history, chart its arteries of funding and influence, and locate its wellsprings of support and aspiration. And we also show how such national issues as Intelligent Design and the death penalty are being debated within the church. It’s been more than 200 years since the founders established the separation of church and state. The assault on that principle now under way promises to alter not only our form of government but our concept of religion as well.