We may be underestimating extinction risks by as much as 100-fold. The problem is that current extinction models treat all individual members as the same. You know, one polar bear is more or less a behavioral, programmed clone of the next polar bear.

We may be underestimating extinction risks by as much as 100-fold. The problem is that current extinction models treat all individual members as the same. You know, one polar bear is more or less a behavioral, programmed clone of the next polar bear.

Ooops. Not so. A new model finds that random differences—male-to-female sex ratios, size differences, behavioral variations—affect individuals’ survival rates and reproductive success. These differences don’t just ripple outward. They tsunami outward into the overall population. Consequently, extinction rates for endangered species can be orders of magnitude higher than conservation biologists previously believed.

The model developed by Brett Melbourne of Colorado University Boulder and Alan Hastings of the University of California Davis monitored populations of beetles in lab cages. “The results showed the old models misdiagnosed the importance of different types of randomness, much like miscalculating the odds in an unfamiliar game of cards because you didn’t know the rules,” says Melbourne.

Some high-profile endangered species like mountain gorillas are already tracked individually. But for many others, like stocks of fish, biologists only measure abundance and population fluctuations. “It’s these species that are most likely to be misdiagnosed,” says Melbourne. “We suggest that extinction risk for many populations… need to be urgently re-evaluated with full consideration of all factors contributing to stochasticity, or randomness.”

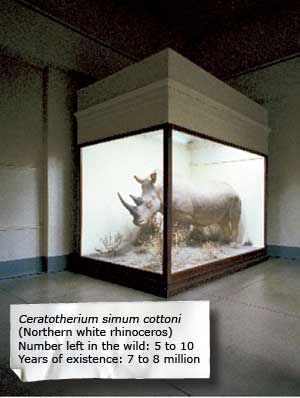

The IUCN Red List tallies more than 16,000 species threatened with extinction worldwide. One in four mammal species, one in eight bird species and one in three amphibian species are teetering on the brink. The new study in Nature, “Extinction risk depends strongly on factors contributing to stochasticity,” makes those numbers look tame.

Julia Whitty is Mother Jones’ environmental correspondent, lecturer, and 2008 winner of the Kiriyama Prize and the John Burroughs Medal Award.