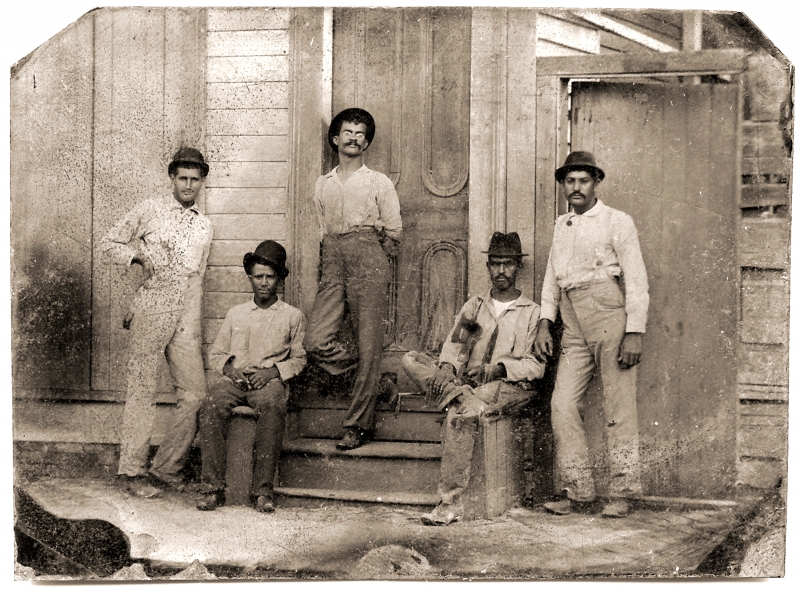

Photo courtsey of Dionne Butler at http://www.tremedoc.com/press/

When people think of New Orleans, they think of the French Quarter, the booze and loud-mouthed shenanigans of Bourbon Street, the balconies and art galleries of Royal Street, the brilliant simplicity of St. Louis cathedral and the statue of Andrew Jackson before it. And, of course, Hurricane Katrina. People don’t think about the Tremé.

This month, PBS airs Faubourg Tremé: The Untold Story of Black New Orleans. The film, by Dawn Logsdon and Lolis Eric Elie and produced by Wynton Marsalis and Stanley Nelson, tells the story of the historically black neighborhood, a story that needs telling: In New Orleans, the civil rights movement went down a little different. In Louisiana, slaves could earn money to buy their freedom. They moved into the Tremé and established the oldest black neighborhood in the United States, where they created the first African American daily newspaper, L’Union, and worked for racial equality. A century before Rosa Parks, African Americans in the Tremé sat where they liked and even commandeered streetcars if whites wouldn’t allow them a seat. After the Civil War they made enormous gains toward equality—desegregating schools, voting in record numbers, and electing a black governor.

Obviously, many of those gains were undone. Throughout the South, newly freed slaves were lynched and tormented, and at the corner of Press and Royal, a black man named Plessy was arrested for boarding a whites-only train car. The ensuing legal battle ushered in decades of separate-but-equal oppression.

The Tremé faced all the deconstructive elements of the last century. Interstate 10 went in over the once oak-lined Claiborne Avenue. The well-to-do moved to the suburbs. Housing projects divided the black and white inhabitants and fostered crime and blight. Crack cocaine and violence decimated the neighborhood in the 1980s. And then, there was Hurricane Katrina. The renovation of narrator Lolis Eric Elie’s Tremé home is almost too painful to watch, as the viewer knows what all that fresh paint faces.

The film has all the quaint elements of a typical PBS documentary: Historic reenactors in dapper costumes walk the streets and read newspaper accounts of events, the narrator speaks over oil paintings, and there are plenty of interviews with historians, musicians, and neighborhood characters. But historical reenactors are hardly necessary. New Orleans lives its history. Houses date back to the 1800s. The music that was born in New Orleans nearly 100 years ago is heard on the streets today. Urban youths show off for their friends with trumpets and master the tricky footwork of dances that can be traced back to Africa. These flashes of authentic and pervasive New Orleans culture ripple through the film: troupes of young black girls dancing in parades, the how-y’all-doings of people on the street, the music of brass bands you only get to hear in parades or very late at night in dance clubs your mother wouldn’t want you going to. Coupled with the mold-ripening stink of flooded houses and the horror on the faces of the people that once lived in them, Faubourg Tremé shows the New Orleans that the nation should see, rather than the New Orleans they often see.

The untold story of the Tremé is the story of the American dream in the least likely of places. At the end of the film, Elie says about the neighborhood, “This rich history doesn’t shield us from our problems, but it does help us deal with them.” New Orleans has problems for sure, but Fabourg Tremé reminds us that not only is it our obligation as a nation to restore it, but that parts of its history could be a model for a brighter future for the city—and for the rest of us.