Possible location identified by SkyTruth of the Scarabeo-9 ultra-deep-water oil rig off Cuba: Satellite background courtesy NASA.

In February Spanish oil giant Repsol YPF began drilling its first well in Cuba’s offshore oilfields in the Florida Straits. Swift currents run through this deep body of water connecting the Gulf of Mexico with the Atlantic Ocean.

The US Geological Survey has estimated the site of this well, the North Cuba Basin, contains 5.5 billion barrels of petroleum liquids and 9.8 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, almost all in the deep water. From Reuters:

The newly built, high-tech rig is operating in 5,600 feet of water, or what the oil industry calls “ultra-deep water,” in the Straits of Florida, which separate Cuba from its longtime ideological foe, the United States. Sources close to the project said such wells generally take about 60 days to complete. Repsol, which is operating the rig in a consortium with Norway’s Statoil and ONGC Videsh, a unit of India’s Oil and Natural Gas Corp, has said it will take several months to determine the results of the exploration.The well is the first of at least three that will be drilled in Cuban waters with the Scarabeo 9, which was built in China and is owned by Saipem, a unit of Italian oil company Eni.

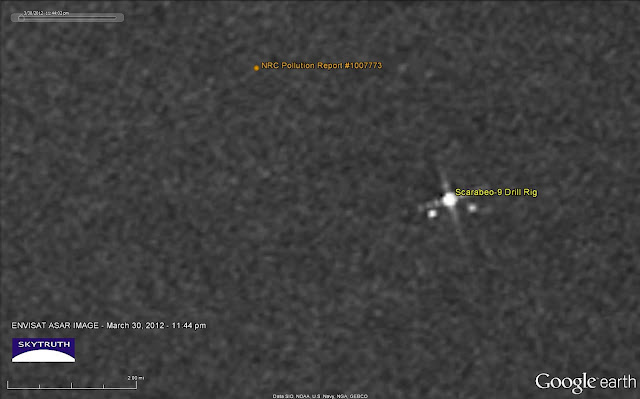

Detail identified by SkyTruth from a satellite radar image of the Florida Straits. “We infer the large bright spot is the Scarabeo-9 semisubmersible drill rig:” Image courtesy European Space Agency.

Detail identified by SkyTruth from a satellite radar image of the Florida Straits. “We infer the large bright spot is the Scarabeo-9 semisubmersible drill rig:” Image courtesy European Space Agency.

Now SkyTruth believes they’ve located the site of the well and the Scarabeo-9 drilling rig in this European satellite image (above):

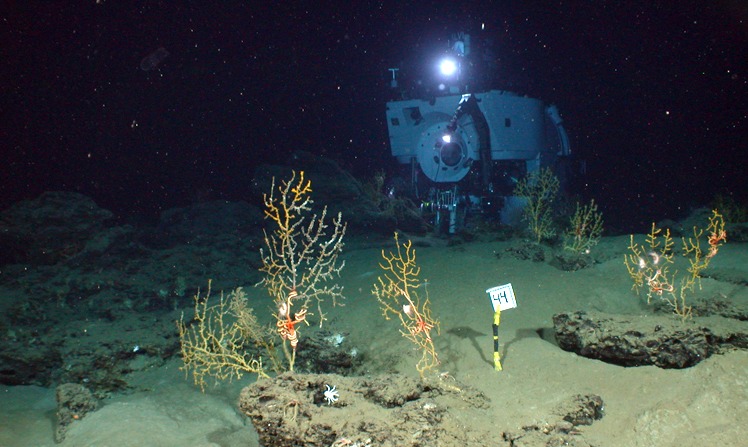

This Envisat ASAR image, shot at 11:43 pm local time on March 30, shows a trio of very bright spots about 17 miles north-northwest of Havana. We think the largest of these spots, with an interesting cross-shaped “ringing” pattern often seen on radar images of big, boxy metal objects, is the Scarabeo-9 rig. The other two spots may be crew vessels or work boats. The location marked in orange is a report we just got through the SkyTruth Alerts that a small possible oil slick was sighted nearby during a US Coast Guard overflight yesterday morning. We don’t think this is anything alarming; it’s probably just some of the typical oily crud you’ll get from an active drilling operation at sea.

Dolphins jumping through oily water from BP’s Deepwater Horizon blowout, Gulf of Mexico, July 2010: NOAA.

Dolphins jumping through oily water from BP’s Deepwater Horizon blowout, Gulf of Mexico, July 2010: NOAA.

It’s unnerving to think of the downsides of drilling so deep there’s no hope of managing a spill without disastrous side-effects. It’s unnerving to think of the long-term effects of such spills.

I recently wrote of the fate of the Gulf of Mexico’s dolphins—particularly the slow and painful demise of the Barataria Bay, Louisiana, population—in the aftermath of BP’s epic fustercluck.

Now NRDC highlights what we know so far about the ongoing unusual mortality event underway with dolphins in the Gulf:

- The die-off has persisted for 25 months.

- The longest die-off prior to this lasted 17 months and was directly linked to a red tide.

- More than 600 bottlenose dolphins have been stranded in the BP spill region since the disaster.

- Roughly 95 percent of those have been found dead.

- Animals whose bodies are recovered in a die-off are the tip of an iceberg, since only 1-in-50 to 1-in-250 marine mammals that die at sea are recovered on Gulf shores.

So 600 dead bottlenose dolphins could scale up to between 30,000 and 250,000 dead marine mammals since BP’s Deepwater Horizon blowout.