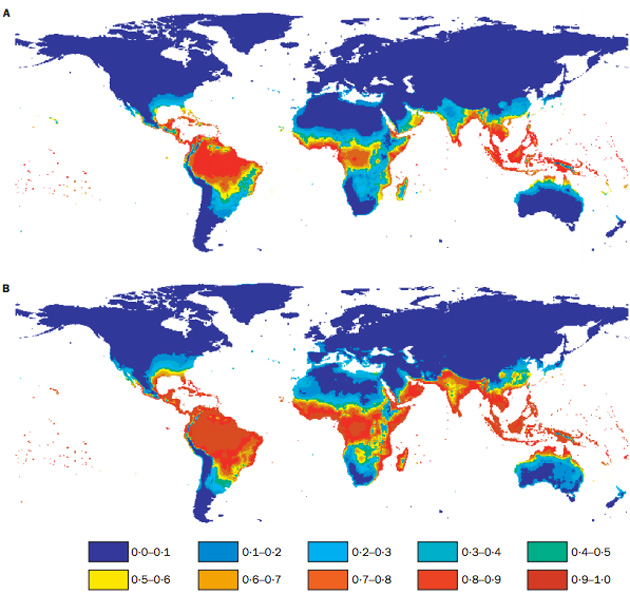

Estimated Population at Risk for Dengue Fever in 1990 (A) and 2085 (B) Based on Climate Data from 1961 to 1990<a href="http://image2.thelancet.com/extras/01art11175web.pdf">Dr. Simon Hales</a>/The Lancet

This past summer, Aedes aegypti—the invasive African mosquito best known for carrying the potentially deadly diseases dengue and yellow fever—made its unexpected debut in California, squirming up from Madera to Clovis to Fresno and the Bay Area.

For a blood-sucking nightmare, Aedes aegypti is surprisingly attractive: Its dark skin and bright white polka-dots make it hard to miss. Unfortunately, it is also notoriously difficult to control. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Aedes aegypti can lay its eggs in less than a teaspoon of liquid and survive without water for months.

While Aedes aegypti has long resided in Texas and the southeastern United States, this is the first time it’s reached California. News outlets have covered the story extensively, but few have mentioned climate change’s role in the mosquito’s spread. The CDC says it’s “likely that Ae. aegypti is continually responding or adapting to environmental change.” In a 2012 report, the World Health Organization (WHO) pointed out that “temperatures, precipitation and humidity have a strong influence on the reproduction, survival and biting rates” of Aedes aegypti.

Climate change studies predict that dengue—which infects as many as 100 million people a year—will expose an additional 2 billion by 2080. In 2009, the mosquito kicked off a Florida outbreak of dengue in a state that hadn’t seen the disease in more than 70 years, and Thailand is currently undergoing its worst dengue epidemic in more than 20 years.

Dengue‘s initial symptoms often resemble the flu, but advanced infections—which cause lung and heart problems, severe abdominal pain, and bleeding from the nose and mouth—kill 15,000 people in 100 countries annually.

Yellow fever is no picnic, either: The disease was one of the world’s most feared before the development of a vaccine in 1936. Its name comes from the illness’ trademark jaundice, and it also causes severe stomach bleeding (often resulting in black vomit). It kills 15 percent of those infected and closer to 50 percent when left untreated.

In the past, yellow fever in the United States made its way as far north as New York City. In 1793, an outbreak even wiped out 10 percent of Philadelphia. Luckily, citizens figured out that they could stop its spread by overturning containers of standing water where mosquitoes bred, and yellow fever was largely eradicated in the United States. In the last 40 years, there have been only nine cases of yellow fever in the United States, all of which were contracted abroad. But in Africa and Central and South America, it’s a much bigger problem: Roughly 200,000 new cases of yellow fever occur every year. Over the last 20 years, outbreaks have occurred in more countries with more frequency, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2010, Uganda had its first outbreak in more than 40 years. WHO reports the increasing number of cases is likely linked to climate change.

There is no vaccine for dengue, and American citizens typically do not get vaccinated against yellow fever unless they travel to a region where it’s endemic. So far, there have been no cases of dengue or yellow fever connected to California’s new Aedes aegypti, and none of the insects have tested positive for the diseases. But public health officials remain vigilant. “We were shocked,” one insect control official in Madera, California, told the Los Angeles Times. “We never expected this mosquito in California.”