<a href="http://www.istockphoto.com/photo/judge-holding-documents-gm489544923-39565112">AndreyPopov</a>/iStock

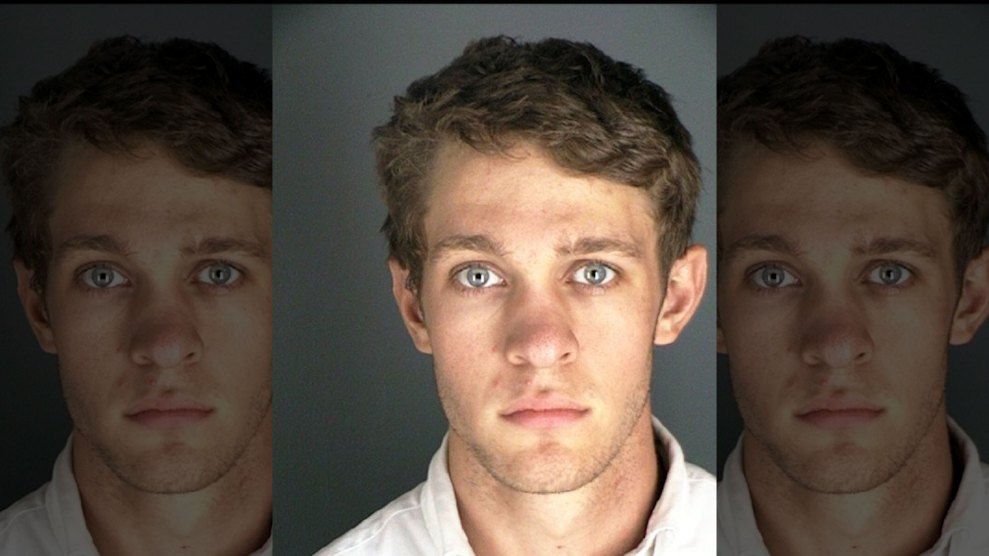

Last week, Judge Patrick Butler had to decide the sentence for Austin Wilkerson, a former University of Colorado-Boulder student convicted of sexual assault. Prosecutors requested prison time. In the courtroom, across from her attacker, the survivor read aloud from a raw, emotional statement about how being raped had affected her life. “Have as much mercy for the rapist as he did for me,” she said to Butler. But the judge sentenced Wilkerson to two years in the county jail, with the option to leave for work or school during the daytime, and 20 years to life on probation.

“I’ve struggled, to be quite frank, with the idea of, ‘Do I put him in prison?'” Butler said at the sentencing. “I don’t know that there is any great result for anybody.”

The scene was nearly identical to the drama that played out in the Santa Clara County Superior Court in June in California, after Judge Aaron Persky sentenced another young white man, former Stanford swimmer Brock Turner, to six months in county jail for sexually assaulting an unconscious woman behind a dumpster. But while Persky now faces a serious and well-funded recall campaign after a petition to remove him from the bench rapidly gained more than a million signatures, Butler hasn’t faced nearly that sort of backlash.

A petition to recall the Colorado judge has lost steam at around 70,000 signatures. Among sexual-assault victim advocates in the state, there’s word of, perhaps, a rally. And the strongest official statement came in the form of a tweet from the Colorado attorney general’s office:

AG: “No prison time for sexual assault sends a terrible message. My thoughts are with the victim” @CCASAColorado https://t.co/sAzZCQlGNU

— CO Attorney General (@COAttnyGeneral) August 11, 2016

Although the Colorado case closely resembles the Brock Turner verdict and sentence, its fallout has been much more muted, largely due to Colorado’s policies on removing judges from office and its sentencing laws.

Unlike in California, where judicial recall campaigns are uncommon but not unheard of, Colorado does not have a clear precedent of recalling district court judges. According to Nancy Leong, a constitutional law professor at the University of Denver, a 2014 state Supreme Court decision outlawing a judicial recall ballot initiative left the core question of judicial recall open, and many believe judges can’t be recalled. “I’m a Colorado native, and I cannot think of a time this has happened,” Leong said.

After the governor appoints a district court judge, voters decide whether to retain that judge every six years. Butler was appointed in 2011, and Boulder County voted to retain him in 2014. He will be up for retention in 2020.

Differences between the two states’ sentencing laws also make it clear that Butler’s decision was not so unusual by Colorado standards. In California, the criminal code required a mandatory minimum of two years in state prison for intent to commit rape, one of the charges of which Turner was convicted. In order to give him a lesser sentence, Persky cited a special exemption in the law that allows judges to substitute probation for a mandatory prison sentence under “unusual” circumstances—which, according to the judge, included Turner’s youth and intoxication.

Butler, on the other hand, did not stray far beyond the constrains of his state’s sexual-assault statute. Wilkerson could have received 4 to 12 years in state prison, but the law also allowed for him to receive a probationary sentence of 20 years to life, said Deputy District Attorney Caryn Datz, who prosecuted the case. While prosecutors and the victim hoped he would get prison time, she said, “It’s important just to acknowledge that this judge has discretion.”

“This isn’t about pointing a finger,” she added.

Still, Datz said, the Wilkerson case is part of a larger trend in Boulder County. “More often than not, we don’t see prison imposed, particularly for young, male college students.”

Part of the blame for that trend may fall on Colorado’s Lifetime Supervision Act, according to Janine D’Anniballe, executive director of Moving to End Sexual Assault, a Boulder County group. The law, known as indeterminate sentencing, requires offenders who are sent to prison for certain sex offenses—including sexual assault—to remain in prison until they complete treatment and apply for parole. In effect, any prison sentence for these offenders becomes life with parole.

For years after the act was passed, Datz said, “it used to be the case that if convicted and sentenced in this category, life did essentially mean that.” But Datz added that for the past five years, the state’s department of corrections has tended to release those prisoners early, correcting the trend. According to the Boulder Daily Camera, judges deciding whether to send sex offenders to prison weigh the possibility that any prison sentence will keep an offender locked away for life. If Wilkerson had been sent to prison, he would have been kept there on an indeterminate sentence.

D’Anniballe says that while she believes Wilkerson deserved a longer sentence, calling it a “slap on the wrist” could be harmful to survivors. “Victims then see that or hear that and conclude that these crimes aren’t taken seriously,” D’Anniballe said. “It might impact their ability to report the crime and follow it through the criminal justice system.”

Even if Butler doesn’t face any serious blowback, the Wilkerson case could affect future sentences in the county. “You bet any Boulder County judge now that’s going to do a sentence on a sex offender is going to be scrutinized,” D’Anniballe said. “I think that’s a good thing.”