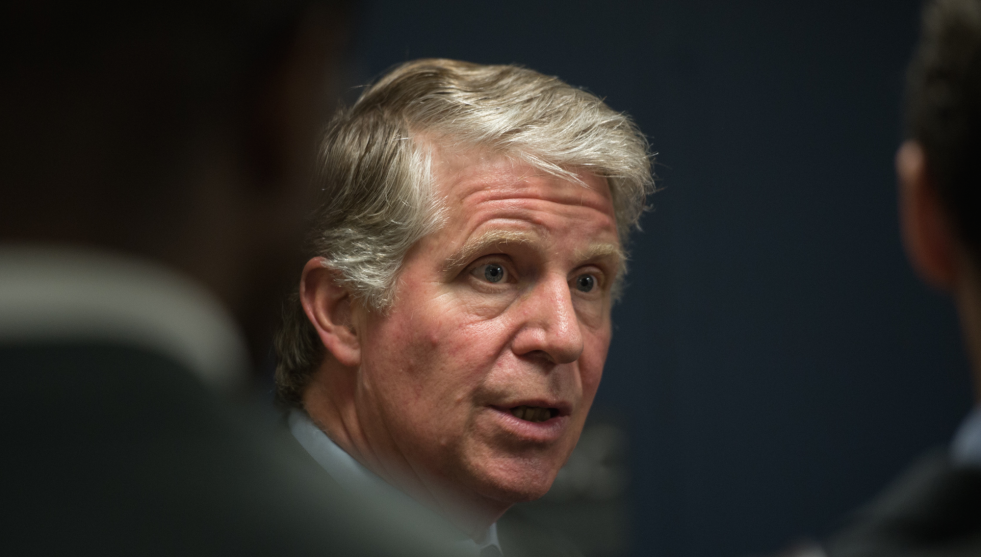

Former New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman leaves his apartment building on May 9.Mary Altaffer/AP

The fall of New York State Attorney General Eric Schneiderman was swift, but it’s far from over.

It took only three hours for him to resign Monday night following the publication of a New Yorker report detailing four women’s accusations that he physically abused them during romantic relationships. Two of the women, Michelle Manning Barish and Tanya Selvaratnam, went on the record to say that Schneiderman, the state’s top law enforcement official and a Democratic champion, repeatedly hit, choked, and threatened them during relationships between 2013 and 2017. The incidents, they allege, caused both women to seek medical attention.

In a statement late Monday night, Schneiderman denied the accusations, but said that they prevented him from effectively doing his job. Meanwhile, Manhattan District Attorney Cy Vance’s office was already telling reporters that it was opening a criminal investigation into the claims—even though Vance himself is being investigated by Schneiderman’s former office over failing to prosecute a 2015 sexual assault complaint against Harvey Weinstein. By late Tuesday, New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo had stepped in, announcing that Vance was off the case and that he was appointing a special prosecutor.

“There can be no suggestion of any possibility of the reality or appearance of any conflict or anything less than a full, complete and unbiased investigation,” Cuomo wrote. “The victims deserve nothing less.”

That special prosecutor is Nassau County DA Madeline Singas, who has spent years focusing on domestic violence and sex crimes. In the coming weeks, she’ll be working with fellow Long Island DA Tim Sini of Suffolk County, where some of the acts allegedly occurred, to determine whether Schneiderman should face criminal charges.

To find out what to expect out of Singas’ high-profile investigation, understand what charges the former AG might face, and comprehend how his own actions as a state legislator might put him in more legal peril, I called up Roger Canaff, a former sex crimes prosecutor in the Bronx who now trains law enforcement on how to build sexual violence cases.

Mother Jones: What’s the first thing Singas will be doing this week?

Roger Canaff: The next step will be for the special prosecutor to surround herself with a team of investigators or detectives. The first thing that they’ll do is attempt extensive interviews with all the women who are willing. One of the first things to establish is, “Where did this happen?” If these crimes took place in the Hamptons, then it’s a Suffolk County case. Obviously, some of these allegations took place in Manhattan, which is New York County. You can only be prosecuted for a crime in the physical or political boundaries of the jurisdiction in which it was allegedly committed.

MJ: What are the other goals of those first interviews?

RC: They’re looking for credibility. Ideally, they’ll be compassionate about it, but certainly they’re going to have to ask the tough questions and they’re going to be looking for details in order to determine what charges can be brought.

There’s allegations that he physically slapped Michelle Manning Barish so hard that it may have created inner ear damage. What she says is that she heard ringing in her ear. She had discomfort for months. She had some bloody discharge. What she was going through could be related to being struck. That verges on a felony assault.

MJ: What range of charges could Schneiderman potentially face?

RC: For misdemeanors, which would include simple assault—like a domestic assault—the statute of limitations is two years. In the case where he struck her so hard she believes she had damage to her ear, that’s serious physical injury. That could be charged up to five years later.

In addition to assault, there are also some sex offense charges, if it’s believed that he acted sexually against one of these women: Sexual abuse, sexual misconduct, rape, whether it’s in the first, second, or third degree. If he used physical coercion in order to complete a sex act against somebody, against their will, there are felonies that describe that behavior. How that’s going to shake out depends on extensive, second-by-second interviews with the women who were involved.

MJ: He also introduced a bill in 2010 that created specific penalties for strangulation—a common aspect of intimate parter violence cases. Could he be charged under that?

RC: Yes. The bill recognized that strangulation is incredibly dangerous, that it’s potentially lethal. It’s possible that he could be charged more seriously under a law that he himself put forward.

MJ: Back when you were a prosecutor, did you ever see cases that resembled this one?

RC: I certainly saw cases involving powerful men. Power and control underlie almost all sexual assault and violence against women cases. I didn’t see the kind of celebrity involved here. He was somebody that had focused on this issue and he had involved himself even further by going after Harvey Weinstein legally, and by being considered somebody who may end up bringing state charges against the president. For those reasons, Schneiderman is an even bigger figure.

MJ: Part of one of the women’s stories is that he used his position of power to intimidate her when she tried to fight back. The quote was, “I am the law.” Does that have any relation to prosecution, or is it just a particularly damning detail?

RC: I would say that it’s probably more of just a damning detail and something that further illustrates just how willing he was to exert control. But people can be prosecuted for misuse of power under various laws that relate to government integrity, so that is a possibility.

MJ: Besides detailed interviews with the women, what other evidence are investigators going to be looking for?

RC: They’re going to want to talk to witnesses who may have observed the injuries, witnesses who dealt with the injuries, and also witnesses that the victim spoke to, probably recently after this occurred.

In the case of the woman who was slapped so severely she had pain and discomfort, they’re going to want to talk to the ear, nose, and throat doctor that she went to. Salman Rushdie is mentioned as a friend of hers, and the New Yorker notes that she made what’s called a “prompt outcry”—meaning she told somebody fairly quickly that these things had happened. In New York state, as in many states, the fact that a witness quickly or within a reasonable amount of time told somebody else, can prove the fact that it actually occurred.

MJ: It seems like those are the same kinds of actions that the New Yorker took to corroborate the stories.

RC: Exactly. The New Yorker appears to have really done a decent job because that’s really what should be happening.

MJ: If we could look into a crystal ball for a second, what do you see as the case’s biggest challenges?

RC: Well, the fact that there’s no physical evidence will make it more difficult. And the fact that law enforcement was not alerted to these acts. What the defense team will probably say is, “These women aren’t powerless. They aren’t the forgotten members of society who are marginalized. These are powerful, independent women. Feminists. If they felt that they were wronged by a man, even a powerful man, they certainly should have felt confident that the law would respond to them—and they still chose not to, which demonstrates that they’re not telling the truth.” That’s not my opinion, but that’s probably what they’re going to say.

MJ: Anything else?

RC: The fact that Manning Barish reconciled with him is going to be difficult. “Well, why would you go back to a person who physically abused you, if this really happened?” Anybody who knows anything about dynamics surrounding sexual assault and intimate partner violence knows that there’s a million reasons why a victim of these things may return to the abusive person. But that’s what the defense team will probably focus on.

MJ: How does the fact that there are four accusers, not just one or two, affect a potential case?

RC: That’s tremendous, tremendous help for the prosecution and the investigator if they’re seeking to prove that these things happened. The case is much stronger given the fact that there are different women, similar in terms of their background and dating pool, I guess, but who are saying very similar things. My guess is the prosecution will try to try them together, and the defense may seek to sever them because in the jury’s mind, of course, these allegations corroborate each other.

MJ: The statement that Schneiderman gave to the New Yorker was, “In the privacy of intimate relationships, I have engaged in role playing and other consensual sexual activity. I have not assaulted anyone and I have never engaged in nonconsensual sex.” What’s your read?

RC: He didn’t issue a flat denial. He didn’t say, “I would never call a woman a whore.” He didn’t say, “I would never put my hands on a woman in any sort of aggressive way.” He may not deny that there was slapping or the demeaning, dehumanizing terms that he used. He may be prepared to say, “Yes, I used those terms, and yes, I did these things. I’ll admit that. I engaged in kinky behavior and I engaged in it in a completely consensual context with these women.”

MJ: And that’s a defense for assault?

RC: Absolutely.

MJ: Going forward, what are you going to be looking for in this?

RC: Are there any other victims? Are there other women who are going to come forward and reveal an even nastier history between him and other people? Then I’ll probably be looking to see how far the state is willing to go, and what sort of bargain, if any, it will seek in order to resolve this.

This interview has been edited and condensed.