Getty

In Georgia, Mississippi, and Ohio, legislators want to make it illegal to end a pregnancy after a heartbeat is detected on an ultrasound. Alabama lawmakers want to do away with abortion entirely. If these bills were to withstand court challenges, they would severely limit women’s overall choices about their own health care. But here’s what hardly anyone is talking about: They’d also likely result in more women dying during labor, delivery, and the weeks after childbirth.

Dr. Tiffany Hailstorks, a Georgia OB-GYN and an assistant professor of obstetrics and gynecology at Emory University, explained it to me this way: The new bills make exceptions for pregnancies in which the mother’s life is in danger. But some medical conditions—certain heart problems, blood pressure conditions, and kidney disease—can be relatively benign in early pregnancy. As the pregnancy progresses though, when conditions are severe—and sometimes during childbirth or the postpartum period—they can become very dangerous and difficult to control, even with medication. “It’s not clear in these bills if these latent conditions would qualify as life-threatening,” said Hailstorks. She added that lack of good prenatal care can make these problems even riskier. That’s especially worrisome because often if a pregnancy is unplanned or unwanted, women delay seeing a doctor. And some states proposing the bans are already dangerous places to have a baby. Georgia’s maternal mortality rate is the second highest in the nation, and Mississippi is 19th.

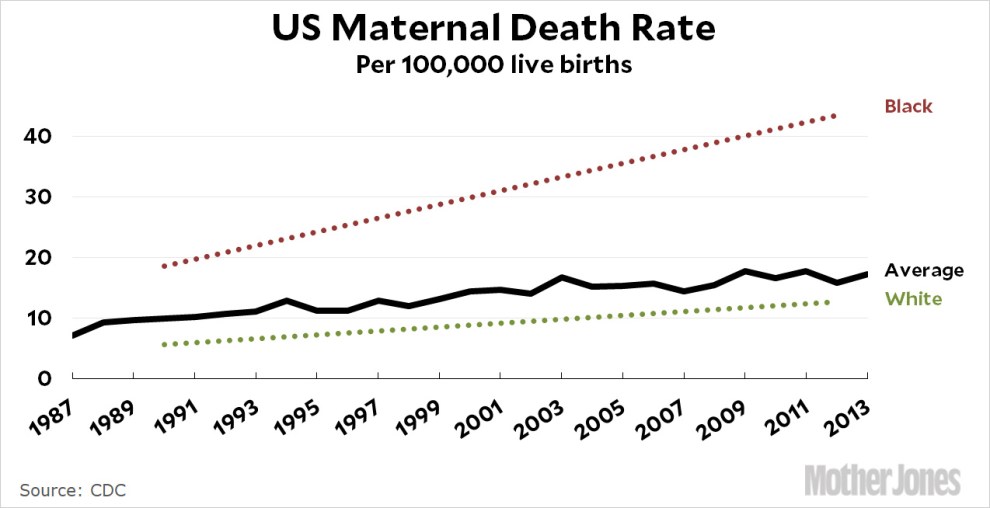

Maternal mortality is on the rise nationwide:

Most striking is that the crisis is especially pronounced among black women, who die during childbirth at nearly four times the rate of their white counterparts, and the rate is increasing more dramatically. Monifa Bandele, the senior vice president of the maternal and child advocacy group Moms Rising, said she worried that the proposed legislation would only intensify that disparity. She pointed to evidence that black women face the double stress of experiencing racism and sexism, which likely contributes to some of the conditions that can compromise a pregnancy—and losing control over pregnancy planning could cause yet more stress, compounding the problem.

“Just think about the stress women would face thinking about being criminalized for having to seek an abortion,” she said. “This is trauma on top of trauma.” She noted that another major cause of maternal death is postpartum hemorrhage, which could become more frequent if women can’t control the timing of their pregnancies. “What if you get pregnant and you have to go back work the next day?” she asked. “We see women who have just had c-sections hemorrhaging on the job.”

Dr. Sanithia Williams, an OB-GYN with the University of California-San Francisco and a fellow of the reproductive rights group Physicians for Reproductive Health, echoed those concerns. “It is black women who have the highest risk of death in pregnancy and around childbirth,” she said. “So what does it mean when women with these risks can’t make decisions about whether to continue a pregnancy? It’s a dangerous situation.”

All the physicians pointed out that it’s not just mothers who the new bills endanger—it’s babies, too. Over the last decade, advances in testing have allowed physicians to identify potentially life-threatening problems early in pregnancy. In the first trimester, physicians can now perform a simple blood draw, known as noninvasive prenatal testing, which analyzes fragments of fetal DNA present in the mother’s blood for chromosomal abnormalities. Some of the most common problems are trisomies—when there are three copies of a given chromosome instead of two. Down syndrome is one kind of trisomy, but others can result in much more severe impairments. Many babies with those trisomies die late in pregnancy or just hours after birth.

In the second trimester, routine ultrasounds can reveal potentially fatal structural problems—like absence of certain organs, or parts of the brain or heart. The proposed bills make no exceptions for these problems, so women whose babies are affected would have to carry the fetus knowing that it likely wouldn’t survive. Williams recalled caring for a mother whose baby was diagnosed with a terminal heart condition during the third trimester of pregnancy—too late to end the pregnancy in the state where she lived. A few weeks later, the baby’s heart stopped in utero, and the woman had to be induced to deliver her stillborn baby. “It was completely devastating,” she said. Williams recalls that she grieved along with the patient, and that she felt a deep sense of helplessness.

Both she and Hailstorks told me they worry that restrictive abortion legislation would compromise their care of patients, going to the heart of the nature of their work. “Most people who go into medicine do it because they want to empower people to make good decisions,” she said. “To be in a situation where there are other options that you know about that would make a patient’s life easier—or even save it—that is really, really hard.”