With a group of seven friends, Brian Anderson, 19, was celebrating senior week on the Ocean City, Maryland, boardwalk: a 3-mile stretch of novelty T-shirt shops, beachfront hotels, and fried food vendors. It was 8:30 p.m. on June 14, their last night in town before they headed back to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and he was smoking a vape in an area where vaping is banned by a town ordinance.

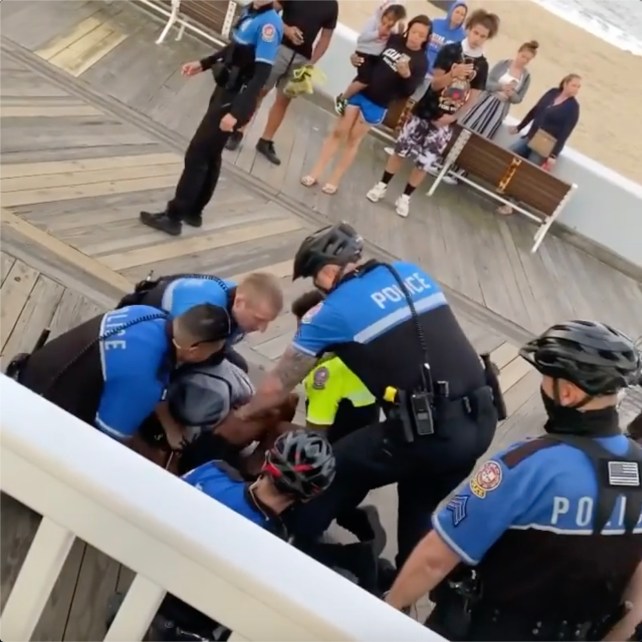

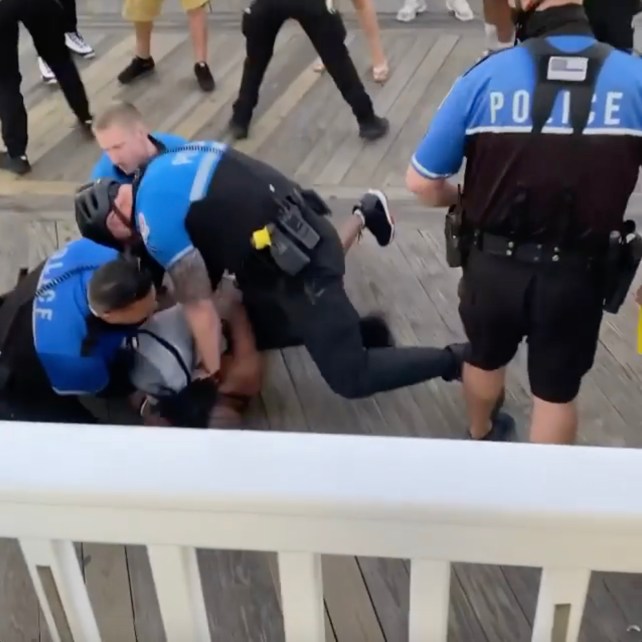

It’s unclear exactly what happened next; by the time a bystander hit record on their cellphone, Anderson was already down on the boardwalk planks, at least five police personnel looming over him. According to the police department’s version of events, Anderson didn’t follow an order to stop vaping, then refused to provide ID—becoming “disorderly,” in law enforcement parlance. Anderson, however, told a Baltimore news anchor that he put his vape away at an officer’s request and started leaving with his friends, but police kept following them. When asked for his ID, he questioned why. “The next thing I know, I’m just on the ground,” he recounted.

In the video, Anderson yells, “I’m not resisting,” as six officers surround him, some holding him down. “Why don’t you tell me what you’re arresting me for?” he shouts. Before he finishes his question, an officer drives a knee into Anderson’s side.

“I just asked God to give me the strength and to guide me, protect me so that this officer doesn’t make this my last day,” Anderson said. He was charged with disorderly conduct, failure to provide proof of identity, second-degree assault, and resisting arrest.

After the video of Anderson’s arrest went viral, yet another video circulated of Ocean City cops tasing a Black teenager accused of smoking on the boardwalk less than a week earlier. In that video, taken on June 6, police confront 18-year-old Taizier Griffin. The police department contends, in a Facebook statement, that Griffin “threatened to kill” officers and spit on them; the video shows only him putting his hands up. When they yell at him to get down on the ground, he reaches his hand toward his backpack strap, is hit by a Taser, and crumples. A bystander says: “It happened last year, too.”

What in the world is going on in Ocean City? Details from the 60-second video of Anderson’s arrest gesture at a decadeslong story of racial exclusion, force, and profit.

The beach

Ocean City’s beach and boardwalk were, for most of the town’s history, reserved only for white people. Black beachgoers could enjoy the sun and sand only on “Colored Excursion Days”: three days in September when business owners sold off leftover food and souvenirs, extracting their last profits of the season. Black families in Maryland flocked instead to properties on the other side of the bay, including Carr’s Beach, which was run by the daughters of formerly enslaved people. To Baltimore resident Mike Lee, who spoke to the Baltimore Times last year, Carr’s Beach offered “a safe haven, a place where we could do what we wanted to do, and not have anyone looking over us, like law enforcement.”

It took a 1955 federal appeals court to legally desegregate Ocean City’s shore along with the rest of Maryland’s beaches. In a lawsuit brought by the NAACP, the court ruled “that racial segregation in recreational activities can no longer be sustained as a proper exercise of the police power of the State.” Yet local business owners refused to integrate, and the town and its tourists remained overwhelmingly white. By 1986, just 2 percent of Ocean City visitors were Black, as were 3 percent of customer-facing resort staff. (Behind the facade, Black people kept the place running, making up 75 percent of kitchen staff, janitors, and housekeepers.)

As of 2019, Ocean City’s full-time residents were 95 percent white, according to the Census Bureau. Yet the tourist crowd, an economic boon the town claims is worth $1.74 billion, has been getting more diverse in recent years, says Rosie Bean, who organized 2020 Black Lives Matter demonstrations on the boardwalk. According to Bean, the demographic shift in tourism has sparked conflict with the town’s white, longtime visitors. “There’s a lot of rebel flags around here,” Bean says. “A lot of racism.” Last year, about a month after Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd in Minneapolis, bundles of KKK literature were found scattered on the sidewalks. The city’s white mayor and police chief participated in one of Bean’s demonstrations, but Bean now looks back on their involvement as “performative politics.”

“They said they want change? They didn’t change anything,” Bean says. “For us, it’s not a PR stunt.”

The show of force

For most of the year, Ocean City is a town of about 7,000 people and 105 police officers. That comes out to about 15 cops per thousand residents—a higher ratio than 99 percent of other police departments, according to the Police Scorecard, a project to analyze law enforcement statistics across the country. But on the average summer day, when tourists pour in, the town population reaches 230,000. So every year in May, the police department doubles its force, partly through the use of “seasonal officers.” Those summer cops, including 46 hired this year, get their guns and powers of arrest after less than a quarter of the training required of year-round law enforcement. Becoming a seasonal officer is a well-worn path to a year-round job at the OCPD. Officer Patrick McElfish, the arresting officer for one of Anderson’s friends, joined the department full-time last year after summer cop gigs in 2018 and 2019.

Seasonal officers’ use of force in resort towns has produced other troubling incidents. In Wildwood, New Jersey, a summer cop punched a woman in the head as part of a crackdown on underage drinking in 2018. On Nantucket, Massachusetts, a group of seasonal and full-time officers injured a group of eight Black youth, smashing one teen’s face into the pavement, after telling them to move off the sidewalk.

Ocean City Police Department’s budget this year totals more than $24 million and costs the town about a quarter of its general fund. By 2024, OCPD plans to hire 33 more cops than the department had in 2020, in a plan so far supported by the mayor and city council. (One councilman, Mark Paddack, was a police officer for 28 years, including 10 years as a police union president.)

At least 13 law enforcement employees are depicted in the video of Anderson’s arrest.

The yellow shirts

In the OCPD, a yellow shirt denotes a “public safety aide”: high school graduates, 17 and a half years or older, some of whom are assigned to patrol shifts after a one-week training. They don’t carry a gun, but they have the power to enforce civil violations, as well as issue parking tickets and transport people who have been arrested. This summer, OCPD hired 60 of them.

In the video of Anderson’s arrest, one of the aides helps hold him down, while others provide crowd control. In the video of Griffin, an aide steps in front of the videographer as police arrest Griffin after he’s just been tased, backing up protesting bystanders.

The thin blue line patch

As he stands over Anderson, one officer reveals his “thin blue line” patch, a symbol of the Blue Lives Matter movement. Andrew Jacob, the white entrepreneur who dreamed up this flag as a college undergraduate, told journalist Jeff Sharlet in 2018 that the black stars and stripes above the blue line represent “citizens…and the black below represents criminals.” Today the flag signifies both support for law enforcement and opposition to racial justice movements. Staff in Maryland district courts are banned from wearing the symbol because of its association with white supremacists.

In a second video from the June 14 arrests, the patch-wearing cop uses a Taser on one of Anderson’s friends as he struggles with two other officers.

The knee

The OCPD did not return multiple requests for comment on the identity of the officer who drove his knee at least five times into Anderson’s side, or with more details around both incidents. But court records reported by Matthew Presnky and Rose Velazquez of Delmarva Now identify the cop driving his knee into Anderson’s side at least five times as “Officer Jacobs.” According to Maryland court records, an Ocean City Police Officer named Daniel Jacobs was involved in the June 14 incident, as the arresting officer for one of Anderson’s friends.

In 2018, an Ocean City officer Patrolman First Class Daniel Jacobs was reportedly one of 16 officers involved in an incident in which a cop punched a restrained Black teenager. Earlier this year, the OCPD awarded him two excellent performance commendations.

Top art source photos: Getty; Instagram; New York Times