Mother Jones illustration; Center for Disease Control and Prevention

As far as viruses go, monkeypox has proven especially challenging to talk about. First, there’s the name, “monkeypox,” which a growing number of health experts say is misleading and derogatory. Then there’s the stigma around sex: While monkeypox is known to spread through skin-to-skin contact of all kinds, officials suspect the disease is commonly spreading during sex, in part due to reports of sores appearing on patients’ genitals or anus.

And then there’s the population most impacted so far: The majority of confirmed cases have been in gay and bisexual men or other men who have sex with men (and a smaller number of trans and non-binary people, some state health department data shows), prompting concerns that monkeypox may be labeled a “gay disease”—which, of course, it is not.

The hurdles don’t end there. Experts also note that monkeypox, which has so far infected more than 5,800 people in the United States and is spreading quickly, is a newly reemergent disease, so there’s still plenty we don’t know about it. Plus, many Americans are already experiencing “virus fatigue” from Covid—all issues that make it harder to discuss monkeypox.

So, how should public health officials and the media talk about the disease in a way that is clear, effective, inclusive, and stigma-free? To put it bluntly, can targeted messaging about gay sex be done without shame? And what can we all learn about how to discuss this virus? I brought these questions to more than half a dozen infectious disease specialists, public health communicators, and advocates. Overall, they said, it’s about trust, clarity, and multiple messages. And they were adamant that clear communication would be a lot more powerful with access to vaccines.

For many, hope was not lost. “It’s really a critical time right now to break the chain of transmission,” says Dr. Peter Chin-Hong, a professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, who specializes in treating infectious diseases. “We have an opportunity to change the ending of the story.”

Here are some big takeaways from our conversations:

The best monkeypox message is not one-size-fits-all.

“There are lots of levels of potential stigma,” says Dr. Wafaa El-Sadr, an epidemiologist and professor at Columbia University. “It makes it rather complicated to find the one perfect message.” If a message is too specific to one group, the rest of the population may “tune out” if they think the risk only applies to that group, says Chin-Hong. And the risk runs both ways: Vague guidance can feel like no guidance at all for groups that are most impacted.

To address this conundrum, Chin-Hong says, “You have to have multiple messages that meet different people in the community. You can’t average a message.”

An effective message may also require different messengers. For instance, Chin-Hong points to a recent television news segment he participated in, which included host Reggie Aquí, a gay man who is “well trusted” by San Francisco’s LGBTQ+ community, and fitness coach Will Hutcheson, a monkeypox patient. “The conversation is very upfront and honest,” Chin-Hong says. At one point, for instance, Hutcheson asks Chin-Hong, “If I have it, does that mean I have immunity, or do I still need to get a vaccine?” Chin-Hong responds that people who contract monkeypox are likely to have some immunity, though experts don’t know for how long. The segment, according to Chin-Hong, was particularly effective because it was hosted by a trusted voice like Aquí.

At the same time, avoid suggesting that only some people are at risk.

Particularly after Covid, the general public may be resistant to hearing about yet another virus and may be primed to see monkeypox as a disease that is of low concern because it is primarily impacting “others,” says Jeff Niederdeppe, a professor of communication who studies health behavior and public policy at Cornell University. “I think part of the knee-jerk reaction that people have to this is like, ‘Please tell me this isn’t something I’m at risk of.’ And so I think that’s an element here, the desire to ‘other’ and minimize risks.”

To be clear: While the virus appears to be spreading primarily among queer men, the virus can infect anyone, “regardless of gender identity or sexual orientation,” the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention notes. (Or, as Queer Eye’s Jonathan Van Ness, a prominent advocate for those with HIV, put it in a recent TikTok, “This is an everyone disease. And monkeypox don’t give a fuck about who you fuck. It’s just trying to get all up in your body.”)

So when it comes to messaging, it’s important to be careful not to further this bias. “One thing that we know is not generally a good idea when you’re communicating about risk is to talk about an issue in terms of relative risk to another group,” Niederdeppe says. “To say, ‘This group is at more risk than another group.'” This can cause people in the less affected group to underestimate their own risk—and can stigmatize others. (We’ve seen this with the coronavirus, too. As I wrote in April, research confirmed that highlighting the racial disparities of the virus led to some white people being less concerned and empathetic about Covid.)

Involve the communities that are impacted.

There’s an old saying dating back to the early years of HIV, originated by disability rights activists, says Jason Rosenberg, a member of ACT UP NY, an AIDS activist group: “Nothing about us without us.” When guidance is created, “by community and for community,” he says, “that’s when we see effectiveness.” In New York, for instance, LGBTQ+ advocates launched an initiative to survey queer and trans people about their monkeypox symptoms and exposure. On its website, the group also provides resources for having safer sex during the outbreak and how to find vaccines in cities all over the country.

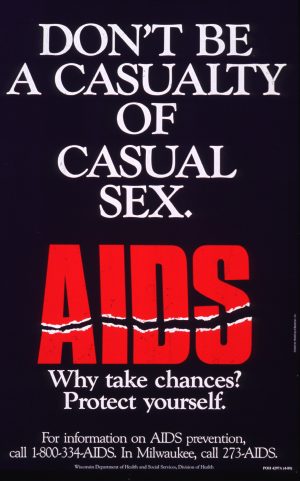

Early AIDS messaging, like this poster from 1988, employed scare tactics which were later found to be ineffective.

“It’s really important to engage the population you’re trying to reach in shaping the message,” El-Sadr says, echoing Rosenberg. “Sometimes you might feel that something is very attuned to the community you’re trying to reach. But when you actually talk to the people, the recipients of the message often have a very different perspective.” For example, she says, early in the HIV epidemic, much of the messaging around the virus was intended to scare people. “And what we’ve learned is, that often doesn’t work.” Positive messages, research shows, are more effective than negative ones.

The guidance is subject to change as we learn more about monkeypox.

Of all the lessons to have learned from Covid, one of the most obvious may be that guidance will change over time. Now, experts say officials and the media should be clearer about our limited understanding of monkeypox. Public health messengers and journalists “don’t often upfront say, ‘Here’s what we know. Here’s how we know it. And here’s what we need to learn,’ or, ‘This is our best set of recommendations now; they might change when we get better information,” Niederdeppe says. Failing to acknowledge uncertainty, he says, can damage people’s trust in messengers. (Remember the CDC’s reversals on masking against Covid?)

In June, for instance, the AIDS Healthcare Foundation recommended that people wear condoms to prevent the spread of monkeypox. “But the evidence supporting using or not using condoms is very poor right now for monkeypox,” Chin-Hong says; according to the CDC, simply wearing a condom is unlikely to prevent the spread of this virus entirely. While monkeypox has been detected in some semen samples, it’s not all, he says. And it’s unclear yet if those viruses were viable (and therefore pose an infection risk). With so much unknown, he says, “I think what that message did to a lot of people in the community was really not make them trust the messenger as much.”

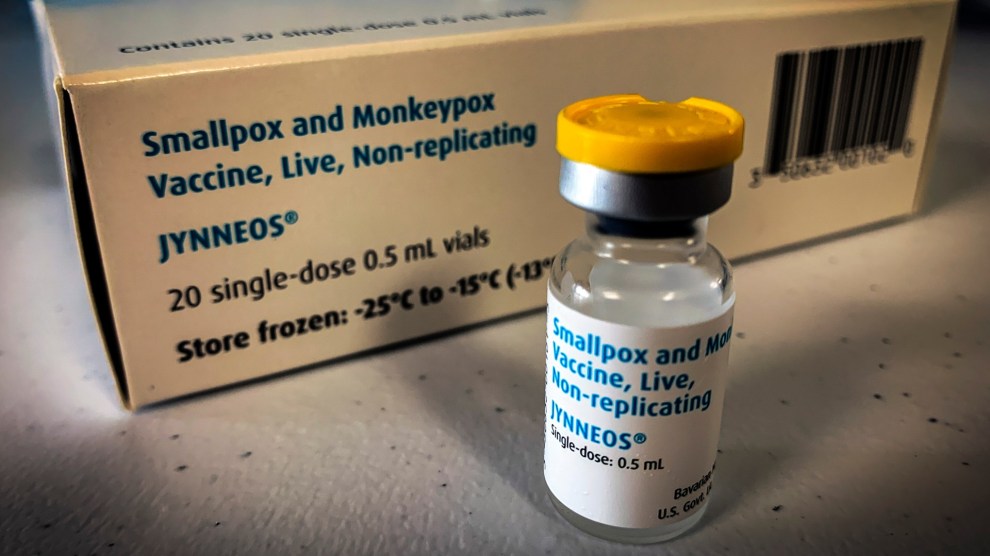

Another big uncertainty is whether monkeypox vaccines will work as well to prevent infection as they did in clinical and animal studies, says Joseph Osmundson, a biology professor at New York University and the author of the 2022 book, Virology: Essays for the Living, the Dead, and the Small Things in Between. “What we learned from Covid on messaging is one of the really, really difficult things is to message the known unknowns, and it is a known unknown how well this vaccine will protect against this epidemic in 2022.”

Other unknowns include whether monkeypox can spread asymptomatically; how often it’s transmitted from respiratory droplets (from, say, coughing or sneezing); and whether monkeypox can be spread “through semen, vaginal fluids, urine, or feces,” the CDC says.

Promote risk reduction, rather than telling people what they can’t do.

If monkeypox can be spread during sex, how do you communicate that risk, without fueling more stigma? “We need to give people resources and options to preserve their safety and the safety of their community when they have sex,” Osmundson says. “Asking people not to have sex will not work, especially medium to long term.” Last week, for instance, Osmundson co-authored a piece in Poz magazine titled, “Six Ways We Can Have Safer Sex in the Time of Monkeypox,” which recommends “sex pods” and temporarily avoiding places with “lots of sexual activity,” like saunas, until the vaccine is widely available to reduce risk of transmission. “How about instead of a slutty summer,” the authors write, “we hold off for a monkeypox-free cider donut anal autumn?”

Chin-Hong also recommends telling people how they can reduce their risk: “You meet people where they are, but you don’t tell people what to do,” he says. “You acknowledge that people are diverse, and they have different needs. And different people have different risk thresholds.” While the exact risk levels of certain activities aren’t totally clear yet, Chin-Hong recommends eventually ranking activities on a spectrum of risk and being clear with people about how to get help if they do get infected.

“Not all risks are the same.” If everything is scary, “you lose the audience,” he says. “Like, OMG, everything is risky, and to hell with that, I’m just gonna do what I want to do.”

Be explicit. It doesn’t help to avoid words like “sex toys,” “anal,” or “masturbate.”

When it comes to communicating risk, many experts emphasize that officials shouldn’t shy away from using explicit sexual language. And for its part, the CDC is doing a pretty good job of this so far. Sure, the guidance from the CDC comes off as “kind of sanitized,” Chin-Hong says, but he was “pleasantly surprised” by how explicit the agency had been.

For instance, I noticed that in a PSA released in mid-July titled, “5 Things Sexually Active People Need to Know About Monkeypox,” a CDC official explains, “Monkeypox can spread to anyone through close, personal, often skin-to-skin contact, including during sex. This includes oral, anal, and vaginal sex, or touching the genitals or butt of a person with monkeypox, hugging, cuddling, massage, and kissing, touching fabrics and objects during sex that were used by a person with monkeypox and have not been cleaned, such as bedding, towels, fetish gear, and sex toys.” The CDC website also lists “virtual sex” and masturbating at a safe distance as ways to reduce your risk of transmission.

This clear guidance, coming from a federal source, is big. “I think it was pretty straightforward and explicit,” El-Sadr says about the CDC’s written guidance. “And it was really unusually so…I have to say, in many ways I thought it was groundbreaking in that way.”

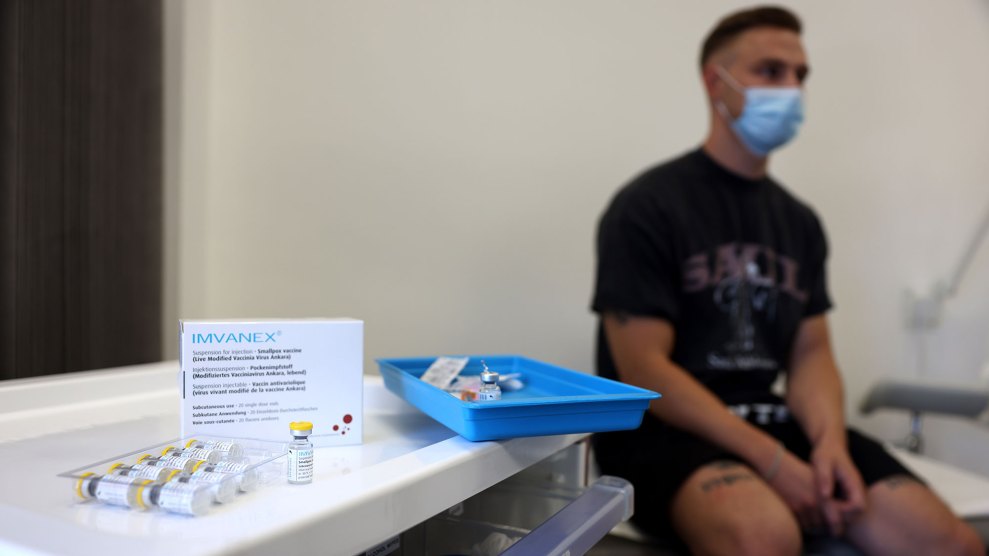

Risk communication would be a hell of a lot easier with access to vaccines.

Messaging is important. But it’s irrelevant in the absence of actual health care. “The frustration that we’ve had is that our partners at every level of government came to the community and said, ‘You need to message.’ And what we found on the ground, was that it didn’t matter whether or not we message because there was no access to testing treatment or vaccination for weeks,” says Osmundson, who in May—days after the first monkeypox case was detected in the US—co-authored an op-ed in the New York Times warning about the lack of resources to fight this virus.

Last week, the Times reported that the Biden administration sat on 300,000 doses of vaccine for weeks after the first cases of monkeypox were detected in the US, adopting “a wait-and-see attitude” about the outbreak, the article notes. “The government could have done something to protect our communities from suffering. And they failed to do that,” Rosenberg says. “They knew it was happening. They saw transmissions live happening on the ground in New York City and beyond. And they chose to do nothing.”

When I asked Osmundson what he’d say like to say to the Biden administration if given the chance, his first message would be, “Number one, get your shit together on the biomedicine that we need.”

“Everyone in my social network knows many people who are ill,” he adds. “And it was preventable, and people are angry. So frankly, the whole conversation about ‘messaging this’ and ‘messaging that’—where were our tools? Where was the urgency to prevent this illness?”