Mother Jones illustration; Justin Sullivan/Getty, Scott Olson/Getty; John Locher/AP

Democracy was on the ballot in key swing states on Tuesday—and in two states the results are still too close to call. Three election-denying Republicans seeking to run their states elections in 2024 lost to Democrats: Kristina Karamo in Michigan, Audrey Trujillo in New Mexico, and Kim Crockett in Minnesota. But in Arizona and Nevada, two key swing states, Trump-backed election deniers Mark Finchem and Jim Marchant are still in contention to lead their states’ 2024 elections—leaving open the possibility for chaos, meddling, and election–hijacking in 2024 if they prevail.

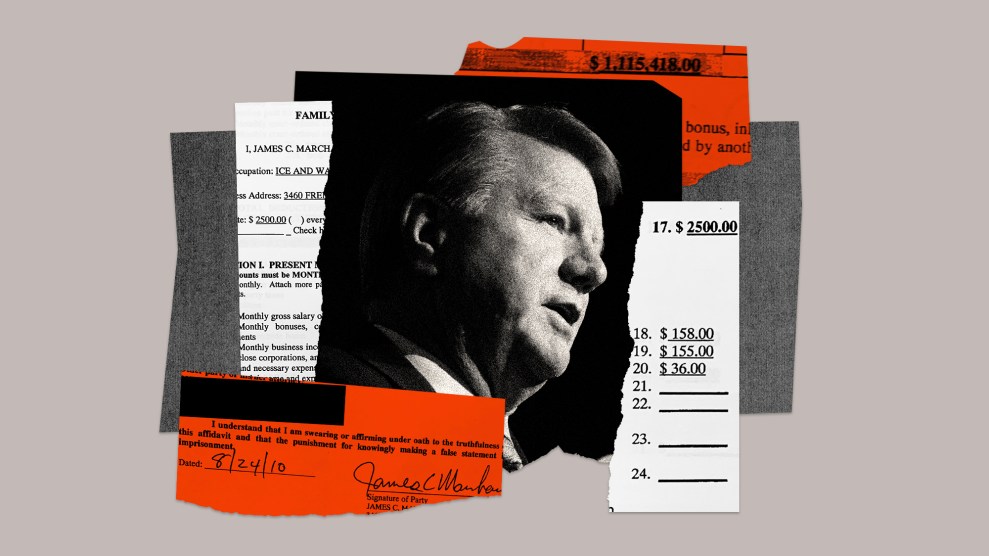

At a rally in Nevada last month, Jim Marchant, the MAGA-styled Republican who may still win his race to be Nevada’s chief elections officer, explained how he and like-minded Trump supporters running for secretary of state could upend the next election if they won in the 2022 midterms. “We’re gonna fix the whole country,” Marchant said, “And President Trump is going to be president again.”

It wasn’t an idle promise. A secretary of state determined to crown a Republican such as Trump the victor in their state would have significant power to create chaos in the 2024 presidential election—and chaos is the first step to election subversion. Armed with the power granted to secretaries of state to oversee elections and to certify their results, a secretary of state could help to undo a Democrat’s victory. The threat is particularly present in swing states such as Nevada and Arizona where the likely close margin between the Republican and Democrat running for president opens the race up to manipulation. In a close race, claims of fraud can carry more sway with the public—it’s easier to claim that 10,000 ballots are fraudulent than 1 million. It’s also easier to change the results through voter suppression tactics or by getting courts to toss a handful of ballots when only a small number of votes separates the two candidates.

As of Wednesday afternoon, both secretary of state races in Nevada and Arizona remained on a knife’s edge. Marchant led his Democratic opponent by about 9,000 votes with an unknown number of ballots—that likely lean toward Democrats—left to count. In Arizona, Democrat Adrian Fontes led Finchem by about 84,000 votes with at least 465,000 ballots left to count.

They’re the last two election deniers still in the running for secretary of state positions, after an election season where a handful got close to election success: In Michigan, Karamo made a name for herself by claiming to have witnessed fraud as a poll observer monitoring Detroit’s absentee counting board. There was no evidence to support her claims. In Minnesota, Republican election denier Kim Crockett, who has a history of bigotry, ran for secretary of state. In New Mexico, ardent election denier Audrey Trujillo, another member of Marchant’s coalition, ran for the secretary of state. All three lost on Tuesday to Democratic incumbents.

Arizona’s Finchem has a similar election-denying history: As a state representative, Finchem claimed to be a member of the Oath Keepers militia group and made multiple attempts to overturn President Joe Biden’s 2020 victory in Arizona. Nevada’s Marchant lost his bid for Congress in 2020, then tried to overturn both his and Trump’s loss. Influenced by a QAnon conspiracy theorist, Marchant decided to run for secretary of state in 2022 and start an “America First Secretary of State Coalition” to deliver the 2024 election to Trump.

A critical administrative position, a secretary of state dedicated to electing a Republican can suppress voter turnout, cause chaos in the vote-counting process, and even help pick the winner after the voting is over. The prospect of any of these election deniers becoming a secretary of state is a “five alarm fire,” says Ellen Kurz, president of iVote, a group that has spent $15 million this cycle to elect Democratic secretaries of state in key battleground states.

“If they’ve said out loud that there’s been a ton of fraud, and the election wasn’t free and fair and Biden didn’t win, and we wouldn’t have certified [the vote in 2020], they’re lying,” says Kurz. But “they’re telling you what they’re going to do next time. Because if they would have done it this time, you have to assume that they’re running on that they would do it next time.”

Even if all five of these Trumpist Republicans loses, Tuesday represented an escalation in a troubling trend: politicization of the position of secretary of state. In 2000, Florida’s secretary of state Katherine Harris co-chaired George W. Bush’s campaign and oversaw the state’s critical recount. In 2004, in Ohio, Ken Blackwell also co-chaired Bush’s campaign while running the state’s election. His tenure, marked by voter suppression tactics, prompted the Columbus Dispatch to ask in a 2005 editorial: “Can an elections chief be so partisan that his ability to manage a clean vote comes into question?” When it came to Blackwell, the paper concluded, the answer was yes.

A decade later, Blackwell’s style was taken up a notch in Kansas, where the anti-immigrant zealot Kris Kobach used his position as the Republican secretary of state to push strict voter ID laws and manufacture the idea of widespread voter fraud—without any proof that it was a widespread problem. His activism on the job showed that what was previously a boring administrative position could be weaponized. Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp used his office to purge voters from the rolls and, days before the 2018 election, launch a last-minute investigation into his opponent, Stacey Abrams, while running for governor. The right’s constant and false drumbeat of fraud made it easier for voters in 2020 to buy the “Big Lie” that the election was stolen.

The election deniers who vied for secretary of state this year represented a new level of threat. Like their predecessors, they support voter suppression tactics, including dramatic limitations on early voting and voting by mail. With the help of Republican legislatures and governors, they could limit mail-in voting, take away ballot drop boxes, affect polling locations, and purge voter rolls. But election-denying secretaries of state also pose a threat to accurately counting the ballots and to certifying the results if their preferred candidate does not win the most votes. These secretaries of state could refuse to certify vote-counting machines, forcing error-prone hand counts, or take the dramatic step of refusing to certify election results they personally dislike.

The threat of this kind of rebellion has arisen before. When Trump narrowly lost the state of Georgia in 2020, he personally called Georgia’s secretary of state, Brad Raffensberger, and asked him to “find 11,780 votes,” to throw the election to him. Raffensberger, a Republican, refused. The leaked call prompted an ongoing criminal probe of Trump in Georgia. In 2024, such a call could end very differently if Marchant or Finchem is on the other end of the line.

What’s more, the very way ballots are counted in elections could be under threat. One result of Donald Trump’s false claim of a stolen election is a distrust of tabulation machines used to count the vote. But tabulation machines are far more accurate than hand counts, and much faster. Hand-counting ballots would significantly slow down the vote count and introduce far more errors into the process—both of which would further erode trust in elections.

We’ve seen the pitfalls of hand-counting already playing out on a small scale in this election. In Nevada, Marchant convinced the rural county of Nye to jettison its vote-counting machines and replace them with a hand count. That hand-count appeared headed toward chaos until the state Supreme Court ordered the county to stop on October 27. Hand-counts could soon become crucial to destabilizing elections: They would create a long, error-riddled process that injects uncertainty into the election, and thus helps build exactly the sort of justification the secretary of state could rely on to refuse to certify an election’s results.

That prospect, which would amount to secretaries of state hijacking elections, is a startling development. Even if Marchant and Finchem go down in defeat in the coming days, the prospect of using the secretary of state position to throw an election has been seeded and will not go away.

The blueprint was laid by Donald Trump in the last two years and has already threatened election results. In 2020, Trump and his allies put pressure on local canvass boards not to certify the election results. In June, Republican commissioners in Otero County, New Mexico, refused to certify the results of the primary over concern about Dominion voting machines—the same company whose machines Trump claimed were manipulated in 2020. The Democratic secretary of state, Maggie Toulouse Oliver, appealed to the state Supreme Court, which ordered the county to certify the results. Two of the three complied after the state’s attorney general threatened legal action if they did not.

The system worked because the secretary of state, the attorney general, and the court stepped in to ensure the election was certified. After Tuesday, that could change: with the vote in Arizona still outstanding, the state could head into 2024 with an election-denying governor in Kari Lake, an election-denying attorney general in Abe Hamadeh, and a GOP-controlled legislature. In Nevada, where the election remains too close to call, the secretary of state and the governor could soon be Trump-backed Republicans—although Nevada’s GOP gubernatorial nominee Joe Lombardo does not believe the Big Lie that Trump won in 2020. The smaller the guardrails, the easier it is will be to manipulate the election results or toss them to the state legislature to decide.

The prospect of state legislatures determining the state’s winner in 2024 will likely become more dire after the Supreme Court decides a case this term called Moore v. Harper, in which the conservative majority is expected to give legislatures more power over their states’ election process. If the Supreme Court takes this radical step, then Republican-controlled legislatures in swing states could attempt to step in to decide the winner in 2024. It’s not yet clear who will control the legislatures in both Arizona and Nevada. Republicans do control the legislatures in the swing states of Wisconsin, North Carolina, Georgia, and will likely retain control in Pennsylvania. (Democrats there may still pull an upset and win the state House as vote-counting continues.) This on its own represents a threat to democracy even though election-denying election chiefs will not be in charge in those states. But the most dangerous scenario when it comes to outright overturning election results is an election-denying secretary of state paired with a legislature and state Supreme Court willing to pick the winner. Whether any state will have that trifecta in 2024 remains unclear.

These realities mixed with the thin margins of any presidential elections could cause chaos. In 2000, Florida decided the president; in 2004, Ohio did. In 2016, Hillary Clinton lost by roughly 72,000 votes spread across just three states. If the vote is once again close in 2024, says Kurz of iVote, just one of these candidates running a swing state election could cause a constitutional crisis.

Looking ahead, election expert Rick Hasen argues, the bulwark against these tactics to undermine election administration and possibly subvert the next election will be state and federal courts. In Nevada’s headcount debacle and New Mexico’s certification crisis, it was state courts that resolved the situation. On Monday, the day before the election, a judge in Michigan tossed out a lawsuit from Karamo in which she requested several changes to election rules that would make it harder for voters in Detroit to have their ballots counted.

As the vote-counting continues, it looks like the unprecedented threat to election administration and democracy this year has been beaten back but not yet defeated. In an ideal world, secretaries of state would make voting easy and secure. For years, some Republican secretaries of state have instead purged voters and put their thumb on the scale through voter suppression tactics. In 2022, voters were faced with election chief candidates running on the promise of ignoring the results of future elections that didn’t go their way. When the results are certified in Arizona and Nevada, voters will either have fended off this extreme threat in the short term—or democracy may face a new kind of test in 2024.