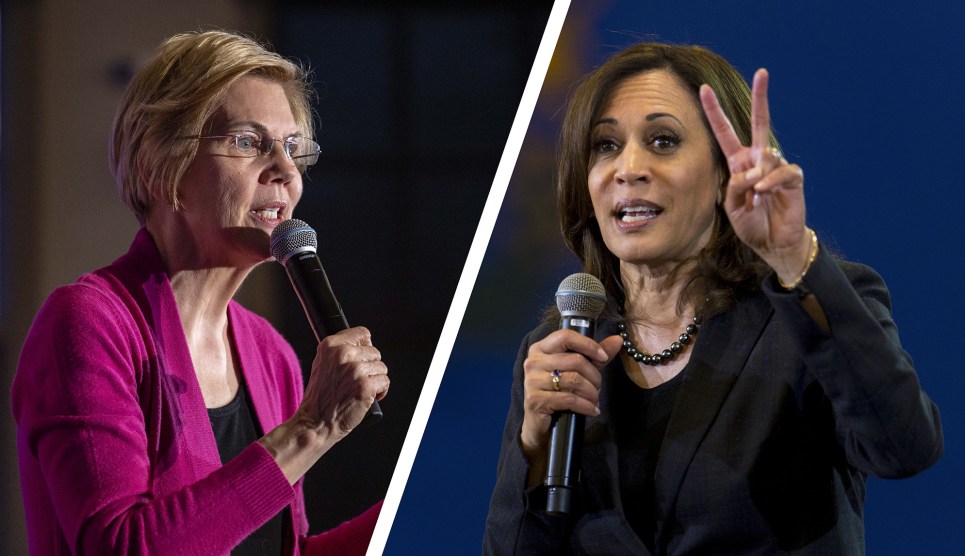

KC McGinnis/ZUMA; Brian Cahn/ZUMA

All the talk these days is about the “theory of change.” Every Democratic candidate is supposed to have one: after all, policy talk is all well and good, but how are you going to actually get legislation passed? Ed Kilgore ponders the problem:

There is not [] any easy equivalence between the audacity of policy proposals and the willingness of candidates to consider the “process” changes that could make achieving these policies possible, as shown by Bernie Sanders, the “radical” who wants to preserve the filibuster and the current system for selecting Supreme Court justices

….These differences matter, perhaps more than policy differences, since progressive ideas are nothing more than fantasies if you don’t have the means to achieve them. It’s easy for Sanders to say he will mobilize enough support for his policies to overwhelm congressional Republicans and force them to go along. But Obama had a similar theory (one that at the time I labeled “grassroots bipartisanship”), and it turned out simply to be wrong once the presidential election ended and things got real.

Quite so. This is why I’m not overwhelmed by, say, Elizabeth Warren’s blizzard of policy proposals. Quite aside from whether I agree with all of them, it’s just cheap talk unless you can get Congress to back you up. Two weeks ago, for example, the House voted 420-0 to ask for the Mueller report to be released. That was cheap talk. When it came time to vote on actual action (i.e., a subpoena), Republicans unanimously voted against it.

It’s good that we’re talking about this, but less good that we’re making it more complicated than it really is. All you have to do is take a look at the past and ask what Democrats needed to pass big liberal legislation and the answer suddenly becomes easy: big Democratic majorities in Congress. That’s it. It’s what made the New Deal possible, the Great Society possible, and Obamacare possible. Its lack is what killed Bill Clinton’s health care plan. There are, it’s true, a few counterexamples of big things that were passed on a bipartisan basis: the Civil Rights Act, the Clean Air Act, ADA, the 1986 tax reform, and a handful of others. However, nearly all of these were passed under Republican presidents and all of them were passed more than 30 years ago.

It’s been more than half a century since Republicans were willing to cross the aisle to vote for progressive legislation. So here’s the only theory of change that matters:

- Get a Democratic majority in both houses.

- Ditch the filibuster.

- Pass whatever legislation is acceptable to the 50th most liberal senator.

This in turn suggests that two things are important:

- The coattails of whatever Democrat runs for president, which is basically her ability to persuade the public to vote for liberal change.

- The ability of the party and the grass roots to elect more liberal senators.

That’s really about it. The precise level of progressiveness of the president matters only slightly since the bottleneck for legislation will almost certainly be Congress. Elizabeth Warren may be more progressive than Kamala Harris, but Harris would still be the better choice if you think her coattails would be stronger, her public appeal for liberal change would be stronger, and therefore she’d be likely to produce a more liberal 50th senator.

Unfortunately, this doesn’t make your decision easier. It makes it harder. It’s fairly easy, after all, to compare candidates based on their stated policy preferences, since those are usually set down in black and white. It’s a lot harder to figure out which one will have the stronger coattails in moderate states. Hard or not, though, it’s what matters.