This is apropos of nothing in particular. I just thought you might want to see how Bitcoin is doing lately:

This is apropos of nothing in particular. I just thought you might want to see how Bitcoin is doing lately:

Tom Williams/Congressional Quarterly/Newscom via ZUMA

So far, Mark Zuckerberg has skated through his congressional testimony without so much as a bruised pinkie. Yesterday produced a grand total of one good round of questions from Sen. Lindsey Graham about whether Facebook is a monopoly, and today has also (so far) produced one good round of questions. It came from Rep. Frank Pallone:

PALLONE: Yes or no? Will you commit to changing all the user default settings to minimize to the greatest extent possible the collection and use of users’ data? Can you make that commitment?

ZUCKERBERG: Congressman, we try to collect and give people the ability—

PALLONE: I’d like you to answer yes or no if you could? Will you make the commitment to changing all the user default settings to minimize to the greatest extent possible the collection and use of user’s data? I don’t think that’s hard for you to say yes to unless I’m missing something.

ZUCKERBERG: Congressman, this is a complex issue that I think deserves more than a one-word answer.

I’ll concede that the old “yes or no” gambit is kind of tiresome, but sometimes it can produce clarity. Facebook’s data collection has always rested on two pillars: its default privacy settings combined with the difficulty of changing them. Neither one by itself is really enough. You need both.

So Pallone wants to know if Facebook will change its defaults. Note that Pallone is not asking Facebook to stop collecting personal data. Not at all. He’s merely asking them to change the defaults so that people have to actively change them if they want to participate fully in the Facebook community. The nice thing about this is that it also provides Facebook with a great incentive to make its privacy settings easy to use. If they were put in a position where users had to understand the settings and know where to find them before Facebook could collect any personal data—well, I think you’d be amazed at just how quickly they could design a really nice, simple user interface for privacy settings.

But of course Zuckerberg gave the usual response to a yes-or-now question: it’s a complex issue that requires more than a one-word answer. But it’s really not. Just turn off data collection by default. Then explain to users the benefits they get if they turn them on. Done.

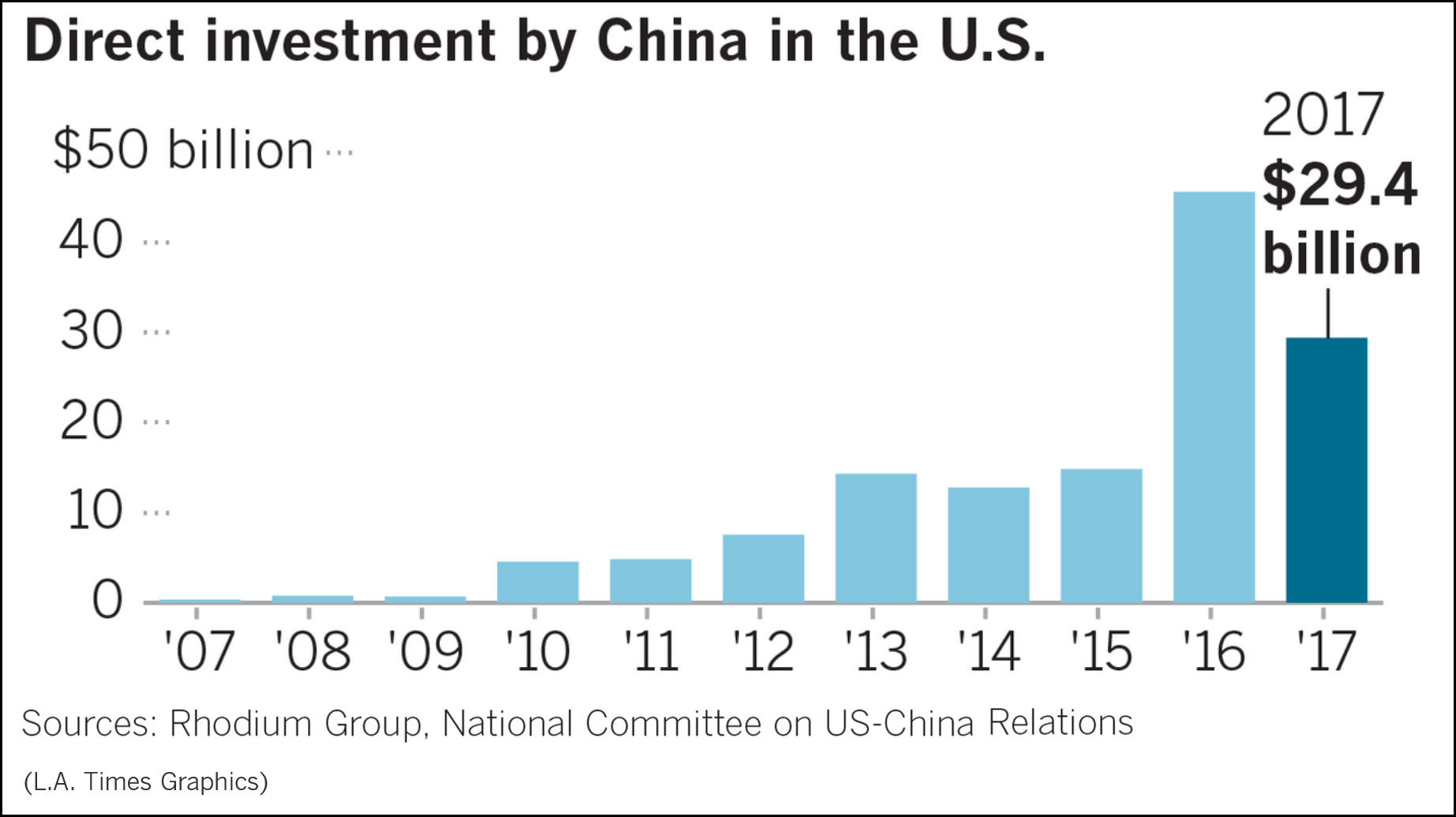

The LA Times reports today that Chinese investment in the US “plunged” last year. “The pullback, which reversed nearly a decade of sharp growth, was underway even before President Trump threatened a barrage of tariffs on Chinese goods amid rising economic tensions between the two nations.”

I was musing about whether I should care about this when I flipped the page and found a chart showing Chinese investment over the past decade:

That puts a different spin on things, doesn’t it? What it really looks like is that Chinese investment in the US is on a fairly steady upward path, with a sudden huge spike in 2016 that China’s State Council decided to rein in. So now my mind is made up: I don’t really care about this.¹

¹With the caveat that if something terrible happens next year as a result of declining Chinese overseas investment, I will naturally claim to have known from the start that this was a big problem the Trump administration ignored for far too long.

This is the lovely new seal Mulvaney commissioned to announce his revised name for the bureau.CFPB

Mick Mulvaney, in a bid to show how serious he is about changing things at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, has proposed changing its name to…

The Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection.

That should get things rolling! He also commissioned a new logo, a time-honored activity for CEOs who don’t really have anything better to do. I suppose it’s better than redecorating his office, though. In the meantime, the BCFP has taken exactly zero actions to protect consumers since Mulvaney took over, and he told Congress today that the bureau’s new mission is “to recognize free markets and consumer choice.” In other words, to do nothing to protect consumers, who are now on their own. Lovely.

Melanie Bell/ZUMA

OK then:

Russia vows to shoot down any and all missiles fired at Syria. Get ready Russia, because they will be coming, nice and new and “smart!” You shouldn’t be partners with a Gas Killing Animal who kills his people and enjoys it!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 11, 2018

So we’re going to fire some missiles at Syria after days and days of thinking it over? That’ll terrify them. Especially since there will be more missiles than last time. Putin and Assad must be quivering in their boots. However, I’ll consider the whole thing a success if the pundits of the nation can refrain from saying how presidential it makes Trump look.

In other news, Paul Ryan is retiring. I guess he wasn’t thrilled with the idea of becoming a backbencher again. But what will he do in retirement? Will he become a Fox News talking head or a K Street lobbyist? The suspense is killing you, isn’t it?

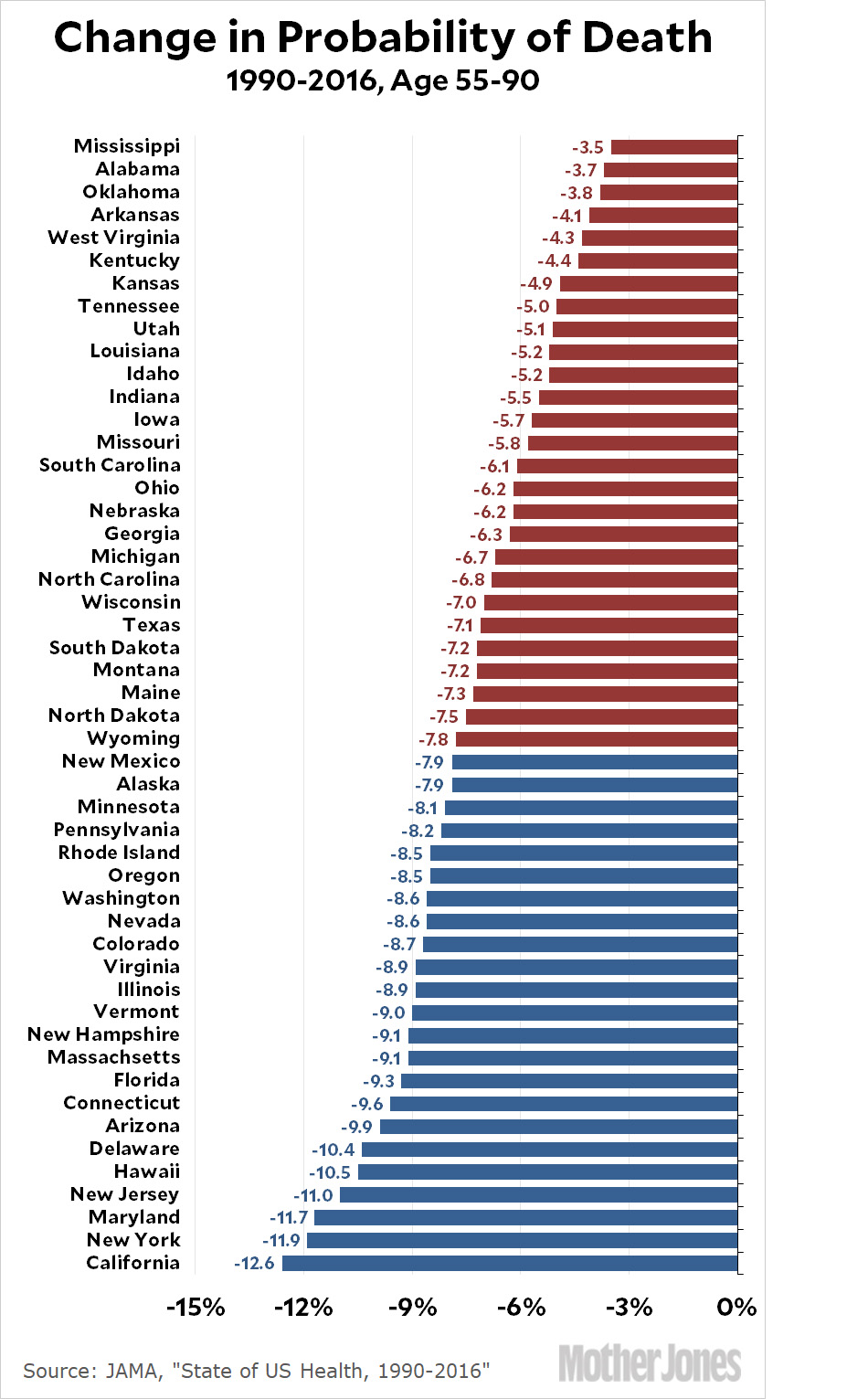

At the risk of being too morbid today, I’m returning to the charts I posted earlier about changes in death rates by state. The charts I posted were for people aged 20-55, but I’m 59 so I was curious about the results for the higher age group. First, here’s the raw data:

Every single state has reduced the chance of dying among the elderly, primarily thanks to huge advances in treating heart attacks. However, the differences between states are still very large. California has reduced the chance of dying by 13 percentage points, from 80 percent to 67 percent, while Mississippi has reduced the chance of death by only 4 points, from 84 percent to 80 percent.

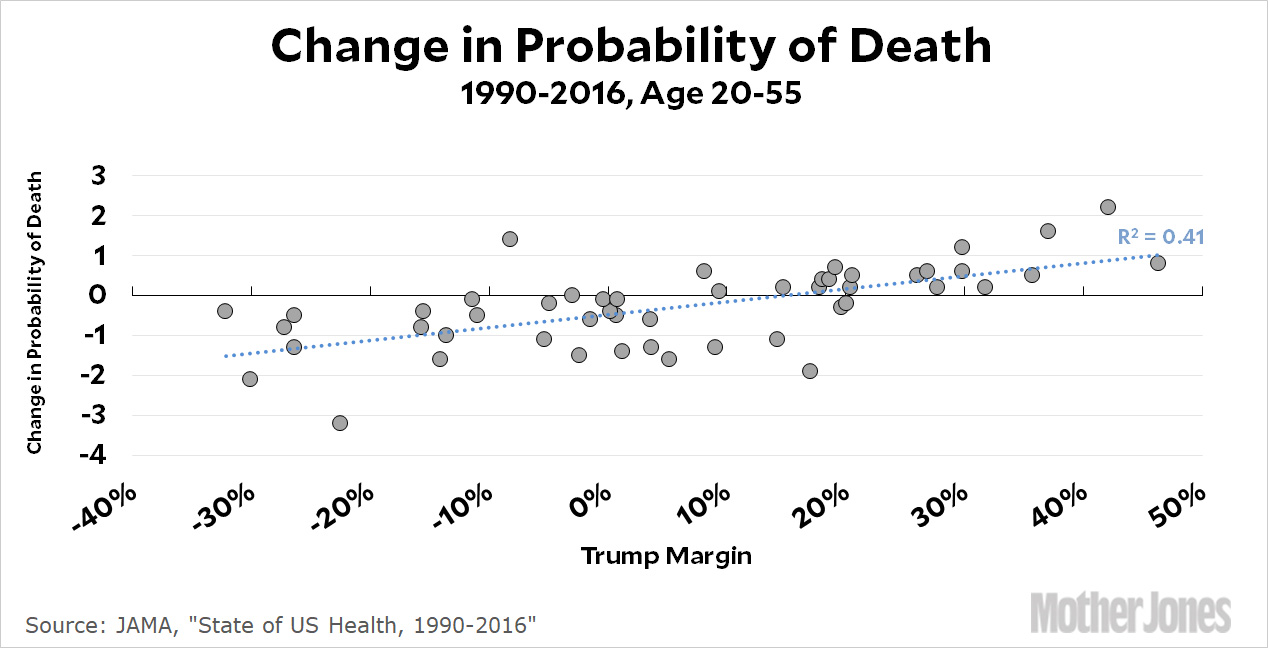

But now for the interesting part. The first thing I noticed about this chart is that it seems to be even more segregated by red and blue states than the chart for the middle aged. That got me curious about the actual correlation between change in health and other factors. At first I tried regressing on the African-American share of each state’s population, but that produced nothing. Then I regressed on each state’s margin of victory for Donald Trump. For the middle aged, the correlation was strong:

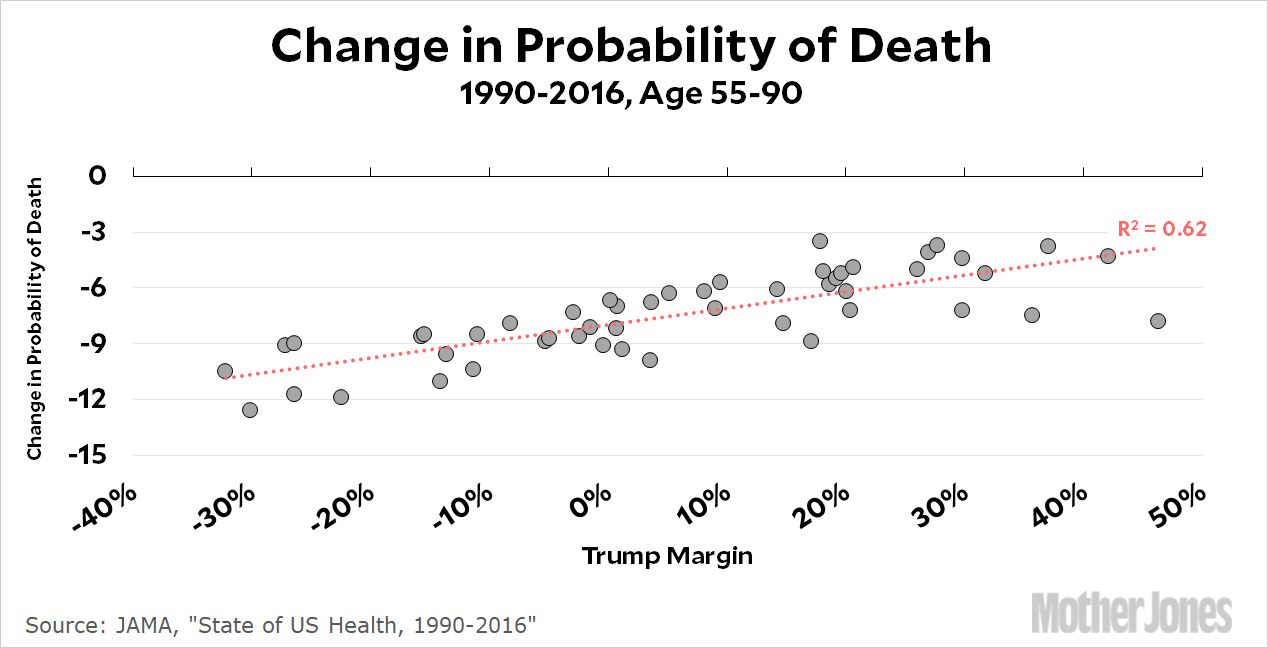

For the older population, the correlation was even stronger:

I know there are all sorts of confounders here, since Trump’s popularity is already correlated with lots of other things. Nevertheless, the better a state does at extending the lives of its residents, the more Democratic it is. The worse a state does, the more Republican it is.

So which way does causation go? Do blue states spend more money on health, and therefore do better on health metrics like these? Or do red state residents do poorly on health metrics, which makes them angry at government and therefore more likely to vote Republican? Or both? Or neither?

One way or the other, though, it sure looks like something is going on. Red state residents continue to vote for low taxes, low services, and Republican government, even though this wreaks havoc with their health. Then they get all bitter and angry because their health is bad and nobody pays attention to their woes, so they vote for Republicans some more. That’s quite the amazing feedback loop.

Stephen Lam/Reuters via ZUMA

As Mark Zuckerberg wriggles his way past a Senate committee that’s pretty clearly overmatched in the IQ department, it’s important to remember why Facebook has such big privacy problems. It’s because Mark Zuckerberg wants it that way. Here he is in 2008 talking about his campaign to get people to stop caring about personal privacy:

The challenge we have is to bring people along that whole path. First, get people onto Facebook and make it so that people can be comfortable sharing information online. Four years ago, when Facebook was getting started, most people didn’t want to put up any information about themselves on the internet. We got people through this really big hurdle of wanting to put up their full name or real picture or mobile phone number.

And again in 2010, telling an interviewer that as Facebook’s campaign to change privacy norms progresses, they try to stay ahead of the curve by reducing privacy protections even further:

People have really gotten comfortable not only sharing more information and different kinds, but more openly and with more people. That social norm is just something that has evolved over time. We view it as our role in the system to constantly be innovating and be updating what our system is to reflect what the current social norms are.

Zuckerberg’s overriding vision from Day One has been unvarying: to get people to share everything about themselves on Facebook. If they do it voluntarily, that’s great. If they don’t do it voluntarily, then Facebook tricks them—and the standard Facebook trick is both simple and surprisingly effective: set privacy defaults as loosely as possible and wait to see if anyone notices. If they do, tighten them the minimal amount needed to quiet the outrage and then do an interview where Zuckerberg talks earnestly about how good their privacy controls are. Rinse and repeat. Facebook has used this approach over and over and over, and it seems to work great no matter how many times they do it.

Of course, one of the big ironies of today’s Senate hearing is that if Congress did decide to get serious about privacy—yes, yes, I know. Stop laughing. Just hear me out. If Congress did decide to get serious about privacy, it might do nothing but benefit Facebook at this point. After all, loose privacy controls aren’t only about targeting ads. They’re also about making it possible for other people to find you. This is what makes a social network grow in the first place. But Facebook already has 2 billion users. That’s nearly every internet user in the world outside China, so there’s a hard limit on their future growth rate.

In other words, stricter privacy controls wouldn’t hurt Facebook all that much at this point. They’d only hurt Facebook’s smaller competitors, who would find it harder to grow as quickly as Facebook did.

It’s still worth doing, though. A good start would be to work with Europe on adopting a common set of privacy standards that are based far more on those in the EU than those in the US. I can dream, can’t I?

I’m sure you’ve noticed that I’ve been playing around with the occasional black-and-white photo lately. It’s hard! I haven’t shot black and white for 40 years, and really, I don’t suppose I was all that good at it in the first place, back when I was a teenager. The darkroom stuff was fun, though.

Anyway, this is a picture of…I dunno. Maybe Mt. Pilchuck? It’s in Washington State east of Everett, more or less, so that’s my best guess. The interesting thing is that this was a terrible photo in color. No matter what I did, it just wasn’t any good. In black and white, though, it’s not bad. It’s still not great, but it’s perfectly respectable.

I’m the farthest thing in the world from a black-and-white nazi. I think most photographs, just like most paintings and most movies, are better in color. But sometimes black and white really is better, usually in cases where the colors are subdued and relatively uniform, and therefore do little except to draw your attention away from the play of light and shadow. This is an example.

BY THE WAY: This was shot through a car window traveling north on I5.

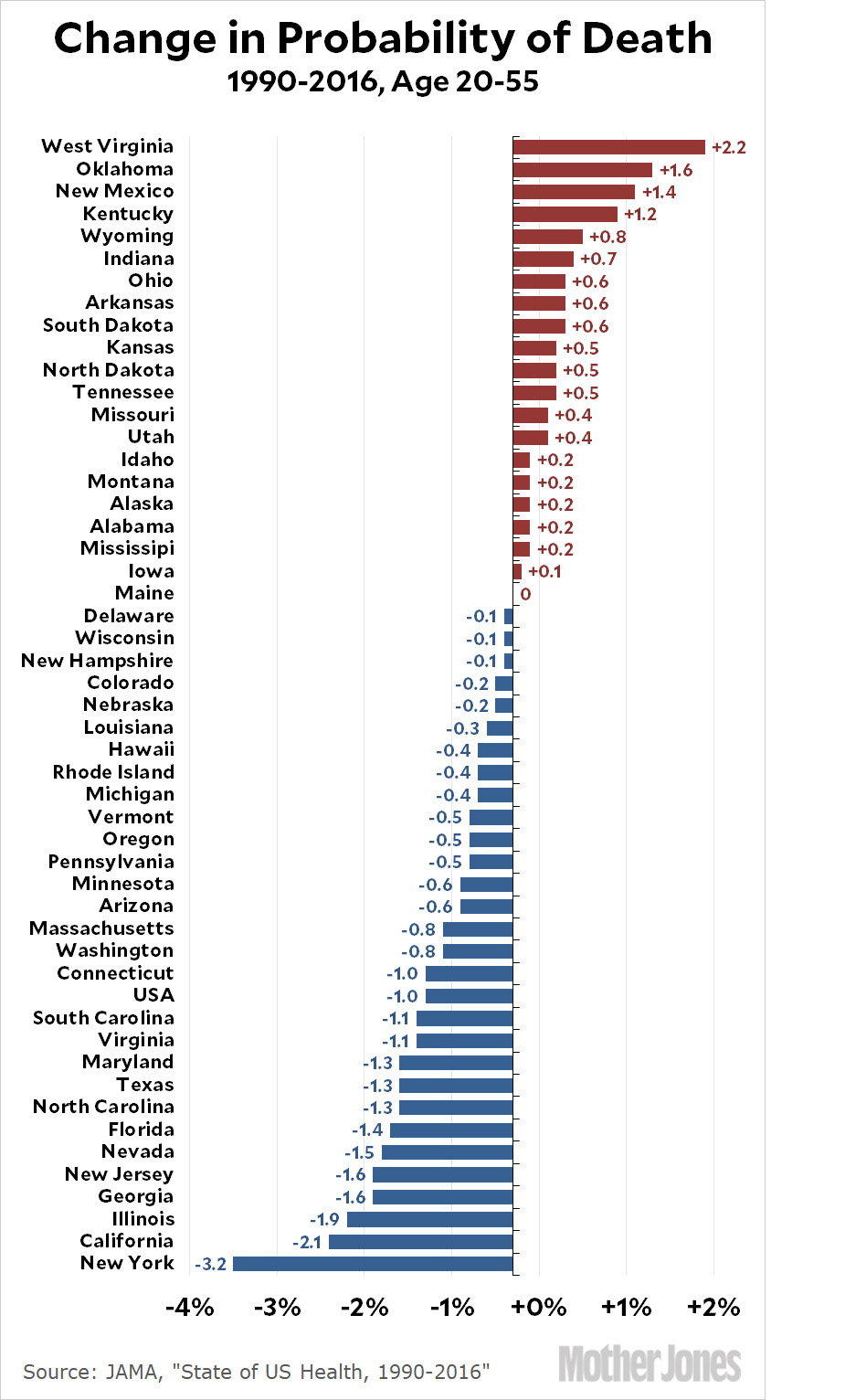

Following up on my post this morning about the change in probability of death between 1990 and 2016, here’s a simplified version of the death chart ranked by state:

In West Virginia, the probability of dying in middle age has increased from about 9 percent to 11 percent. In New York it’s decreased from 9 percent to less than 6 percent.

It’s easy to look at this chart and notice that it’s mostly red states that have gone downhill. And that makes you wonder why they keep voting for Republicans. Why not vote for Democrats who take health care more seriously? This seems like absurd behavior until you look at it from a different angle: a lot of people in red states see (and live through) stuff like this and conclude that government doesn’t work. That being the case, why not vote for the party that says it wants to reduce government?

Following up on last night’s post about Syria, let’s do an assessment. How has America done in its various military interventions in the Greater Middle East (spanning North Africa through Central Asia)? This has to be judged against (a) the goals of each intervention and (b) the long-term consequences. Here’s a quickie list of the major interventions since the Reagan Era:

You could add a few others if you want—Pakistan, Yemen, the Iran/Iraq war—but I’m just hitting the highlights here. Without getting into endless arguments over details, the bottom line is that the US has had seven major interventions in the Greater Middle East over the last 40 years and either six or seven failures, depending on how you evaluate the Gulf War. In fairness, I’d add that the post-9/11 mission in Afghanistan could have been fairly successful if it had been limited and properly staffed. Most likely, that was a failure of political stupidity, not an inevitable result.

Excuses aside, though, the roll call is grim. The goals of American interventions have spanned the gamut from modest peacekeeping to regime change. With one arguable exception, none of these interventions had a positive impact on either the Middle East or the interests of the United States. Taken as a whole, they’ve been instrumental in creating the War on Terror we’ve been fighting since 9/11. Anyone who wants to be taken seriously when they argue for further US interventions needs to honestly engage with this history and then explain why this time will be different. And it better be a pretty good explanation.