Wang Lei/ZUMA

This story first appeared on the Atlantic Cities website and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

In the wake of climate-related disasters, rebuilding is never just a matter of putting back the structures that were there before a storm. It needs to address the intangible, too, beginning with carefully considered strategies for economic recovery.

When Superstorm Sandy ripped through the Northeast, it caused both acute short-term economic losses, and also sustained economic challenges. Businesses were shuttered, insurance claims lagged, and out-of-pocket expenses continue to affect families, small business owners and communities.

Any rebuilding effort needs to address prospects for economic recovery along with any physical designs.

Hurricane Sandy caused billions of dollars in property and infrastructure damage. Nearly 650,000 houses, 300,000 businesses and 250,000 private vehicles were damaged or destroyed.

The trauma to the region’s infrastructure was monumental. The New Jersey Transit Authority rail operations center, inundated by seven feet of water, lost 74 locomotives and 294 rail cars (its repair bill would constitute $400 million of the $2.9 billion losses in the state’s transportation system). A nine-foot storm surge in Lower Manhattan flooded eight tunnels, destroyed the South Ferry Whitehall Street subway station, and caused $7.5 billion in damage. Airlines canceled 20,500 flights in the six days before and after the storm. Shipping came to a standstill, reducing fuel imports dramatically. Further, nine million households and businesses were without power. Within three days, the region, especially New York was paralyzed by a gasoline shortage.

The threats to the economy rippled out too. Businesses did not have power, and the New York Stock Exchange closed for an unprecedented two days. All told, by May 2013, analysts reckoned the economic losses from Sandy in the tri-state area amounted to $64 billion, 89 percent of the total cost.

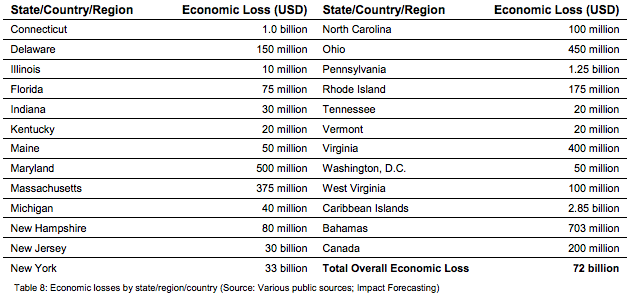

This chart lays out the economic costs of Sandy by state:

In plotting a way forward for economic recoveries in the future, there are important and useful lessons to be learned from Hurricane Katrina, the costliest natural disaster in American history.

In an essay from Rebuilding Urban Places After Disaster: Lessons from Katrina (which I co-edited), chief Moody’s economist Mark Zandi offers a roadmap for economic recovery after a crisis. The tenets he outlines ought to be considered in future natural disasters as a way to recoup losses and stage an economic comeback.

- Provide short-term and other financial assistance to distressed households through unemployment insurance, health and medical support, housing assistance, and provision of goods and services.

- Once immediate, short-term recovery assistance has been secured, governments should identify key export-based industries or businesses that are large employers, have a community leadership role, or that support other businesses. These should be the first to receive government aid as a way to provide the most effective economic stimulus. If these businesses are crippled, others will have a hard time recovering.

- Give households temporary relief in meeting mortgage, tax and credit card debt and support local governments so they can borrow funds to carry out rebuilding projects.

- In the aftermath of the storm, focus first on infrastructure improvements that get people back to work. Immediately connect the labor force to jobs, facilitate movement of goods, and provide households with access to basic necessities. If necessary, use stopgap measures to get the job done, but position the rebuilding efforts as a way to create infrastructure systems that are more sustainable, cost-effective and that enhance an area’s general livability.

- Implement incentives for housing construction or reconstruction, including tax breaks, clear or favorable zoning guidance, and support for those raising housing above base-flood-elevation levels.

- Facilitate a well-functioning insurance market in order to stimulate rebuilding in the right places. Offer help with safe places, but not in places prone to flooding and other natural disasters.

By looking at Hurricane Sandy through this lens, we can see the region has a good deal of room for improvement. The most important lesson of all, however, is the recognition that the region’s economy is fragile because of the vulnerability that comes from the coastal locations of people, jobs and facilities. Designers and stakeholders working at rebuilding after Sandy should carefully assess whether the rebuilding process will leave them better able to rebound economically when another storm strikes.