Over at Wonkblog, Dylan Matthews has a long post titled “Why do people hate deficits?” It’s a good summary that runs through all the various reasons people give for thinking that deficits are bad.

But it doesn’t actually answer the question, at least not as I take it. Dylan’s list provides us with two things: (a) technical reasons that some economists dislike big, persistent deficits, and (b) talking points used by politicians who are railing against the deficit and need to toss out some plausible sounding arguments. What we’d really like to know is why so many ordinary people dislike deficits. Here are a few possibilities:

- They listen to politicians and pundits railing against the deficit and simply assume that deficits must therefore be bad. After all, everyone says they are.

- They don’t really care about deficits, they just hate welfare spending. Opposing the deficit is a convenient proxy.

- They think that countries are like households, and getting in debt inevitably means an endless, grinding stuggle to pay the bills.

- Liberals have done an abysmal job of explaining why deficits are good during periods of high unemployment, so ordinary citizens have no reason to think deficits are anything other than bad.

I imagine all of these things play a role, but I’d place a lot of weight on the last one. Sure, some of the reasons to dislike deficits are dumb and some are downright dishonest. But that’s just the nature of political discourse. A movement that can’t fight back against slippery arguments had better steel itself to lose lots of battles.

Like it or not, the truth is that deficit hawkery is a pretty obvious default position to have unless someone gives you a really compelling reason to believe otherwise. So if we’re unhappy that the public is too hawkish about the deficit, we have only ourselves to blame.

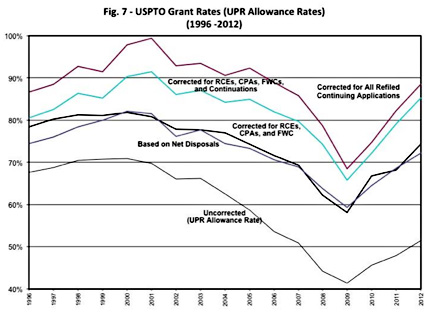

patent applications are approved. The headline result is that the patent office got steadily more selective during the Bush administration, and then suddenly reversed course in 2009 and started approving way more applications.

patent applications are approved. The headline result is that the patent office got steadily more selective during the Bush administration, and then suddenly reversed course in 2009 and started approving way more applications.

euro. But regardless of whether you love her or hate her, I think Michael Tomasky makes an astute point

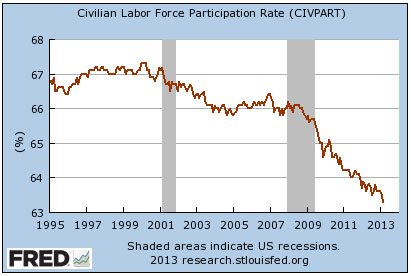

euro. But regardless of whether you love her or hate her, I think Michael Tomasky makes an astute point  of 3 million. So Feroli’s contention is plausible: the upward spike in disability awards might account for about a quarter of the post-recession downward spike in labor participation.

of 3 million. So Feroli’s contention is plausible: the upward spike in disability awards might account for about a quarter of the post-recession downward spike in labor participation. model….Sometimes you have to make dramatic changes to save the jobs that you can,” he said.

model….Sometimes you have to make dramatic changes to save the jobs that you can,” he said. businesses, afraid that this would hurt the tourist trade, decided to band together and pay for the snowplows themselves.

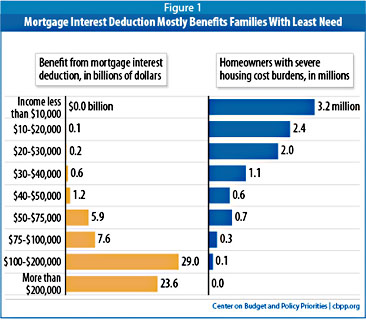

businesses, afraid that this would hurt the tourist trade, decided to band together and pay for the snowplows themselves.  deduction is $8 billion. The one-third of families above that receive a benefit of $60 billion.

deduction is $8 billion. The one-third of families above that receive a benefit of $60 billion.