As we all know—because what could be more fascinating than reading about statutory capital requirements for systemically important banks?—one of the best ways of insuring that big banks are less likely to fail is to require them to hold more capital. The more capital they  hold, the bigger the losses they can suffer without going belly up and destroying the global financial system.

hold, the bigger the losses they can suffer without going belly up and destroying the global financial system.

After our most recent brush with financial death in 2008, the world’s central bankers all started beavering away on new capital requirements. They eventually produced Basel III, hoping that it would do a better job of ensuring bank safety than the ill-fated Basel II. Unfortunately, although there are some good ideas in Basel III, the capital requirements are only modestly more stringent than the old standards, which proved to be so catastrophically inadequate during the Great Meltdown.

So lefty senator Sherrod Brown and right-wing senator David Vitter have teamed up to propose tighter capital requirements for U.S. banks. Under their bill, all banks would have a minimum capital requirement of 10 percent, and big banks would have even higher requirements. Hooray! But Mike Konczal reports that it’s not all roses:

It is interesting that the Brown-Vitter bill would replace, rather than supplement or modify, Basel III. Basel III has a leverage requirement that does similar work to the extra equity requirements Brown-Vitter recommends. That rule is only set at 4 percent, instead of 10 percent, but could be raised while keeping the rest of the Basel rules intact.

….Basel III isn’t just capital ratios, though. Another important element is its new liquidity requirements. Liquidity here refers to the ability of banks to have enough funding to make payments in the short term, especially if there’s a crisis. Basel III includes a “liquidity coverage ratio,” which requires banks to keep enough liquid funding to survive a crisis.

Financial institutions have been lobbying against an aggressive implementation of Basel IIl’s liquidity requirements. They saw a small victory when some of the requirements were pulled back in the final rule in January. Brown-Vitter would remove them entirely — a remarkable win for the financial sector if the proposal passes.

Basel III is a floor, not a ceiling. National regulators all have the authority to require higher capital ratios, or to tighten up the quality of capital banks are required to hold. In fact, doing that would be, by far, the easiest way to deal with bank safety.

So why throw out the whole framework? For one thing, capital ratios are calculated as capital / assets, and Brown-Vitter raises the ratio by requiring more capital and by changing the way assets are valued. Maybe that’s a good thing. There’s a lot of justifiable suspicion that “risk weighting” of assets just allows banks to play complicated regulatory games to meet their capital requirements. It might be a good idea to do away with that completely, rather than simply reforming it, as Basel III does.

I probably need to noodle on this some more, but my insta-reaction is that we’d be better off leaving Basel III alone, risk weighting and all, and simply raising the capital ratios. My instinct tells me that global finance is simply too complex these days to pretend that all assets are created equal. We should let Basel III play out on that front and see how it does. We should also keep Basel III’s liquidity requirements, since liquidity problems were a core part of the bank failures of 2008.

So: Just raise the ratios and demand that banks hold more high-quality capital. That’s simple and effective. Better to do that than to try to rewrite Basel III from scratch.

POSTSCRIPT: There’s an easy metric that should give us a pretty reliable idea of whether the Brown-Vitter approach is a good one. Just wait for reaction from banks. If they’re cautiously supportive, it’s a bad idea. If they attack it, then maybe it’s a good idea. Wait and see.

and the public that Republican intransigence is what’s standing in the way of a grand bargain.

and the public that Republican intransigence is what’s standing in the way of a grand bargain. chicken. So if you just blindly plug the increased price of beef into your spreadsheet, you’ll end up generating an inflation number that doesn’t accurately reflect the actual consumption patterns of ordinary consumers.

chicken. So if you just blindly plug the increased price of beef into your spreadsheet, you’ll end up generating an inflation number that doesn’t accurately reflect the actual consumption patterns of ordinary consumers.

Paul Waldman notes today that on virtually every website, lists are

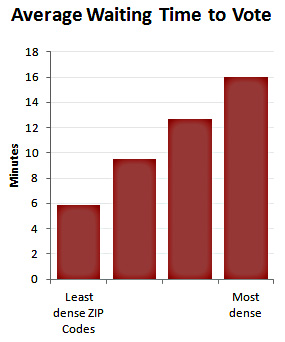

Paul Waldman notes today that on virtually every website, lists are  border states.1 And within states, areas with dense populations have the highest wait times.

border states.1 And within states, areas with dense populations have the highest wait times.  hold, the bigger the losses they can suffer without going belly up and destroying the global financial system.

hold, the bigger the losses they can suffer without going belly up and destroying the global financial system.