<a href="http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2010/06/10/president-obama-meets-with-congressional-leaders-bp-spill-and-months-ahead">Pete Souza</a>/White house

Today is Sequestration Day! To celebrate, all of your most burning sequestration questions are answered right here. Enjoy.

Where did the whole idea of sequestration originate? It goes back to 1985. The tax cuts of Ronald Reagan’s early years, combined with his aggressive defense buildup, produced a growing budget deficit that eventually prompted passage of the Gramm-Rudman-Hollings Act. GRH set out a series of ambitious deficit reduction targets, and to put teeth into them it specified that if the targets weren’t met, money would automatically be “sequestered,” or held back, by the Treasury Department from the agencies to which it was originally appropriated. The act was declared unconstitutional in 1986, and a new version was passed in 1987.

Sequestration never really worked, though, and it was repealed in 1990 and replaced by a new budget deal. After that, it disappeared down the Washington, DC, memory hole for the next 20 years.

What about the 2013 version? Where did that come from? In the summer of 2011, Republicans decided to hold the country hostage, insisting that they’d refuse to raise the debt ceiling unless President Obama agreed to substantial deficit reduction. After months of negotiations over a “grand bargain” finally broke down in July, Republicans proposed a plan that would (a) make some cuts immediately and (b) create a bipartisan committee to propose further cuts down the road. But they wanted some kind of automatic trigger in case the committee couldn’t agree on those further cuts, so the White House hauled out sequestration from the dustbin of history as an enforcement mechanism. It would go into effect automatically if no deal was reached.

In the end, no immediate cuts were made, but a “supercommittee” was set up to propose $1.5 trillion in deficit reduction later in the year. To make sure everyone was motivated to make a deal, the sequester was designed to be brutal: a set of immediate, across-the-board cuts to both defense spending and domestic spending, starting on January 1, 2013. The idea was that everyone would hate this so much they’d be sure to agree on a substitute.

Needless to say, no such agreement was reached. So now we’re stuck with the automatic sequestration cuts.

How big is the sequester? You’d think this would be an easy question to answer. In fact, it’s surprisingly complicated! Are you ready?

The basic amount of the sequester is $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction over 10 years. But when you reduce spending, you also reduce interest on the national debt. This means that we only need $984 billion in actual program cuts. And since it’s for 10 years, naturally that means we divide by nine to get annual spending cuts of $109 billion. For FY2013, this comes to $12 billion per month, because there are only nine months from January (when the sequester begins) through the end of the fiscal year in September.

But wait! The fiscal cliff deal in January delayed the sequester until March 1, so it also lopped off two months of cuts. This means that the total amount of spending cuts for this year clocks in at $85 billion.

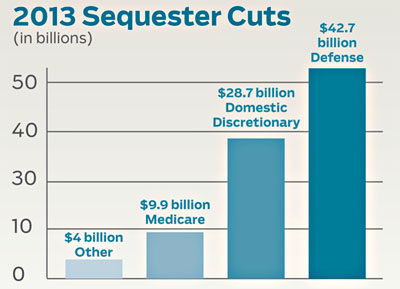

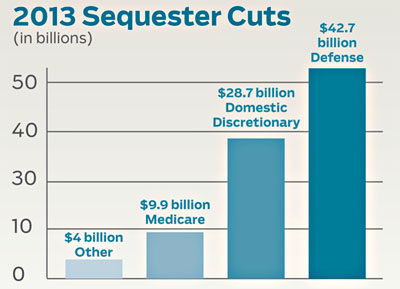

So what gets cut? The sequester is split evenly between defense spending and domestic spending. The domestic half has two parts: Medicare and everything else. For Medicare, the sequester specifies a flat 2 percent cut in reimbursements. Doctors will continue to bill  at their usual rate, but they’ll only receive 98 cents on the dollar. According to the Congressional Budget Office, here’s how the whole thing nets out (see Table 1-2):

at their usual rate, but they’ll only receive 98 cents on the dollar. According to the Congressional Budget Office, here’s how the whole thing nets out (see Table 1-2):

- Defense: $42.7 billion

- Medicare: $9.9 billion

- Other domestic: $32.7 billion

Aside from Medicare, how are the other cuts divvied up? The sequester legislation requires the cuts to come evenly from every budget account. This means everything (with a few exceptions) gets cut the same amount. It’s an especially stupid way to cut spending, since everyone agrees that some programs are more important than others, but that’s the way it is. If you really want to torture yourself, you can read this Office of Management and Budget report, which contains 224 pages listing the sequester amounts from every single agency in the United States government. It’s followed by another 158 mind-numbing pages of agency accounts that are exempt from the sequester.

But as stupid as this is, don’t get too excited about it. It’s only for FY2013, which lasts seven more months. After that, although the total amount stays in place ($109 billion, split evenly between defense and domestic spending), congressional appropriations committees have much more flexibility about how to juggle the cuts.

Aren’t we still in a recession? What are these cuts going to do to the economy? Technically, we’re no longer in a recession, but there’s no question the economy remains weak. A big bunch of dumb spending cuts is about the last thing we need.

That said, the actual impact of the cuts is hazy. Among private forecasting firms, Macroeconomic Advisers figures the sequester will cut GDP by 0.7 percentage points, while IHS Global Insight puts it at 0.3 percent. Back before the sequester was delayed, CBO estimated 0.8 percentage points. Given a consensus growth forecast of about 2 percent for this year, this is a fairly substantial headwind. In terms of jobs, it will probably increase the unemployment rate by about half a percentage point. This is why Fed chairman Ben Bernanke basically told Congress on Tuesday that they were nuts to let the sequester proceed.

That’s all sort of bloodless. How about some horror stories? You know, three-hour waits at airports because of TSA cutbacks, food poisoning epidemics thanks to USDA cutbacks, that sort of thing? The White House has been making a lot of hay over its 50-state breakdown of cutbacks. California, for example, will lose 1,200 teachers, 8,200 Head Start slots, 49,000 HIV tests, $5 million in meals for seniors, etc. You can see the forecasts for your state here. Aside from that, Wonkblog seems to be the go-to site for alarmist coverage of the sequester. Brad Plumer has the impact on R&D spending here. In an interview with Ezra Klein, former NIH director Elias Zerhouni says it will be a “disaster for research.” Suzy Khimm interviews a former Homeland Security official here who says smuggling will increase. And MoJo‘s own Zaineb Mohammed lists six ways the sequester will hurt the environment here, including higher risk of damage from wildfires.

That’s terrible! Does anyone have a plan to avoid the sequester? Sure. Sort of. President Obama has proposed a substitute that includes about $1.1 trillion in spending cuts and $700 billion in new revenue. It was dead on arrival because Republicans are flatly unwilling to consider any plan that includes higher taxes. Back in December, Republicans in the House passed a bill that would have kept all the domestic cuts and replaced the defense cuts with yet more domestic cuts, mostly to anti-poverty programs. It was DOA too, for obvious reasons. House and Senate Democrats have plans as well.

But the truth is that there’s probably no deal to be made. Republicans won’t accept tax hikes, Democrats won’t accept any bill that’s exclusively spending cuts, and neither party is willing to just kill the sequester outright, which is the most sensible option. For now, all that’s really happening is that both sides are barnstorming the country blaming the other guys. Obama seems to be winning that battle at the moment.

I’ve actually made this point twice today already, but both times it’s been buried in a longer post. So here’s a post that just says one thing:

I’ve actually made this point twice today already, but both times it’s been buried in a longer post. So here’s a post that just says one thing: sympathy. Today I’m declaring victory. Dan himself links to the

sympathy. Today I’m declaring victory. Dan himself links to the  The insanity of laws that basically prohibit sex offenders from living anywhere is reaching new heights in Los Angeles. Several itsy-bitsy new parks are being built in the city,

The insanity of laws that basically prohibit sex offenders from living anywhere is reaching new heights in Los Angeles. Several itsy-bitsy new parks are being built in the city,

at their usual rate, but they’ll only receive 98 cents on the dollar. According to the Congressional Budget Office, here’s how the whole thing nets out (

at their usual rate, but they’ll only receive 98 cents on the dollar. According to the Congressional Budget Office, here’s how the whole thing nets out ( federal government has an interest in making sure that states don’t abridge the right to vote based on race or skin color. When the Supreme Court upheld the VRA in South Carolina v. Katzenbach, it explicitly noted that preclearance

federal government has an interest in making sure that states don’t abridge the right to vote based on race or skin color. When the Supreme Court upheld the VRA in South Carolina v. Katzenbach, it explicitly noted that preclearance  The House finally reauthorized the Violence Against Women Act today despite the opposition of more than half the Republican caucus. Steve Benen thinks this means

The House finally reauthorized the Violence Against Women Act today despite the opposition of more than half the Republican caucus. Steve Benen thinks this means