Ramesh Ponnuru provides us with a brief summary of today’s Republican budget proposal in the House that “changes the Senate plan in several ways that are designed to make it more palatable to Republicans.” I’ll provide an even briefer summary: it removes the one thing Democrats wanted and replaces it with four new items that Republicans want.

Ezra Klein writes that “on a policy level, there’s really very little difference between this and the Senate deal.” That’s true. But there’s a huge difference in principle: the Senate plan is a genuine deal, giving Democrats something they want and Republicans something they want. The House plan, as usual, is a laundry list of Republican demands that offers nothing in return except a short-term extension of the debt limit and a short-term CR. The wish list might be smaller than it used to be, but the House deal very plainly still uses the debt ceiling as a hostage for the passage of a set of Republican demands. Greg Sargent confirms that Democrats understand this perfectly well:

Dem Rep. Chris Van Hollen, a key ally of the Dem leadership and White House, told House Democrats at a private meeting today that a vote for the new House GOP plan is a vote for a deliberate Tea Party effort to sabotage the emerging Senate deal.

In an interview with me, Van Hollen strongly suggested it will get no Democratic votes, which could call into question the ability of Republicans to pass this plan through the House, as some conservatives are already balking at it because it raises the debt limit.

“This has no Democratic support,” Van Hollen told me. “It is a recipe for default. The Democratic leadership told the caucus that a vote for this is a vote for default and for keeping the government shut down. Democrats understood that this is exactly what this was.”

This is going nowhere. President Obama has set out one thing very clearly: he won’t make concessions to Republicans as a direct quid pro quo for raising the debt ceiling. That’s what the House deal does. If Democrats supported it, they know perfectly well that the result would be yet another list of demands next year when the short-term extensions run out. It’s dead on arrival.

UPDATE: As it turns out, the Republican plan couldn’t even get enough Republican votes in the House. So everything is back on the Senate’s doorstep now.

Today, in an interview at WonkBlog, Robert Laszewski, the president of Health Policy and Strategy Associates,

Today, in an interview at WonkBlog, Robert Laszewski, the president of Health Policy and Strategy Associates,

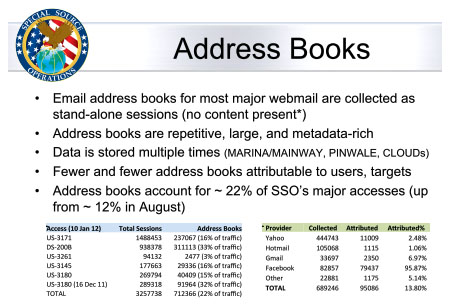

Yes, the NSA is collecting your

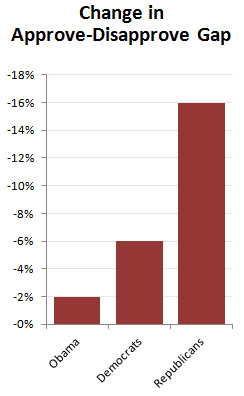

Yes, the NSA is collecting your  Another poll, another disaster for the GOP. According to the latest ABC/Washington Post poll, the approval rating of the Republican Party has cratered ever since the budget showdown started. The gap between approval and disapproval has dropped by 16 points for the Republican Party in just two weeks. The change for Democrats has been only 6 points, and for President Obama there’s

Another poll, another disaster for the GOP. According to the latest ABC/Washington Post poll, the approval rating of the Republican Party has cratered ever since the budget showdown started. The gap between approval and disapproval has dropped by 16 points for the Republican Party in just two weeks. The change for Democrats has been only 6 points, and for President Obama there’s  Whichever party wins the most seats is the winner of the election.

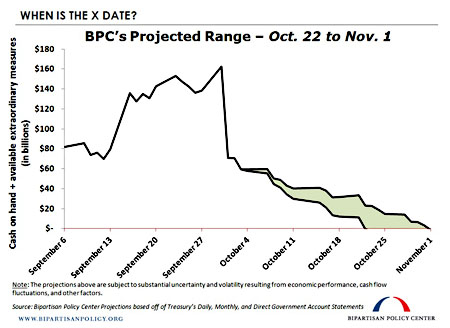

Whichever party wins the most seats is the winner of the election. Obama to take sole responsibility for raising the debt ceiling over the next two years until his authority ran out.

Obama to take sole responsibility for raising the debt ceiling over the next two years until his authority ran out.