Is there a higher-education bubble? Will technology produce cheaper, better alternatives in the near future? Are kids and parents finally figuring out that if Bill Gates can drop out of Harvard and become the richest man in the world, maybe an Ivy League degree isn’t  actually worth 50 grand a year? Dan Drezner thinks the whole idea is ridiculous, and he’s willing to put his money where his mouth is:

actually worth 50 grand a year? Dan Drezner thinks the whole idea is ridiculous, and he’s willing to put his money where his mouth is:

If, in fact, there really is a higher ed bubble, it should pop before 2020. And if it does pop, then tuition prices for college should plummet as demand slackens. After all, that’s how a bubble works — when it deflates, the price of the asset should plummet in value, like housing in 2008. So who wants to bet me that an average of the 2020 tuition rates at Stanford University, Williams College, Texas A&M and the University of Massachusetts-Lowell will be lower than today?

I’m open to changing the particular schools, but those four are a nice distribution of private and public schools, elite and not-quite-as-elite colleges, with some geographic spread. Surely, true believers in a higher ed bubble would expect tuition rates at those schools to fall.

I really don’t think that will be the case. So anyone who believes in a higher ed bubble should be happy to take the other side of that bet.

Not me. I’d be willing to bet that eventually artificial intelligence will basically wipe out the demand for higher education completely. But “eventually” means something like 30 years minimum, probably more like 40 or 50. Maybe even more if AI continues to be as intractable as some people think it will be.

In the meantime, Drezner is right: the vast, vast majority of college students don’t want to strike out on their own and try to become millionaire entrepreneurs. They just want ordinary jobs. And that’s a good thing, since if everyone wanted to run their own companies, entrepreneurs wouldn’t be able to find anyone to do all the non-CEO scutwork for their brilliant new social media startups.

So if something like 98 percent of college grads are aiming for traditional jobs in which they work for somebody else, guess what? All those somebody elses—which probably includes most of the people who think there’s a higher-ed bubble—are going to want to hire college grads. They sure don’t want to hire a bunch of losers who were too dim to drop out and become millionaires and couldn’t even manage the gumption to accrue 120 units at State U, do they?

Look: the rising cost of higher education has multiple causes, but it’s mostly driven by two simple things. At public schools, it’s driven by declining state funding, which transfers an increasing share of the cost of higher ed onto students. Unfortunately, I see no reason to think this trend won’t continue. At private schools, it’s driven by the perception of how much a private degree is worth—and right now, all the evidence suggests that even with fairly astronomical tuitions at elite and semi-elite universities, the lifetime value of a degree is still worth more than students pay for it. Universities understand this, and since these days they mostly think of themselves not as public trusts, but as businesses who simply charge whatever the traffic will bear, they know they still have plenty of headroom to increase tuition. So this trend is likely to continue as well.

If I had to guess, I’d say that there’s a class of 2nd or 3rd tier liberal arts colleges that might be in trouble. They have high tuitions, but the value of their degree isn’t really superior to that of a state university. They might be in trouble, and if Drezner added one of these places to his list it might make his bet more interesting.

But he’d still win. He might lose by 2040, but he’s safe as long as he sticks to 2020.

little under $2.38.

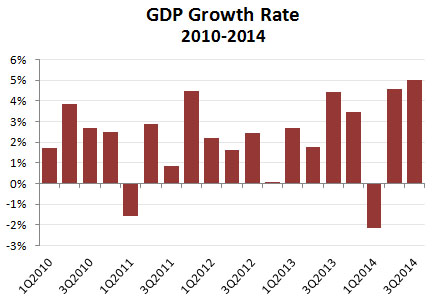

little under $2.38. Part of this is still a make-up for poor growth in the first quarter, but it’s good news nonetheless. The economy really does seem to have

Part of this is still a make-up for poor growth in the first quarter, but it’s good news nonetheless. The economy really does seem to have  So if you want to support our great journalism….

So if you want to support our great journalism…. Austin Frakt writes about the stunningly widespread

Austin Frakt writes about the stunningly widespread  actually worth 50 grand a year? Dan Drezner thinks the whole idea is ridiculous, and he’s willing to

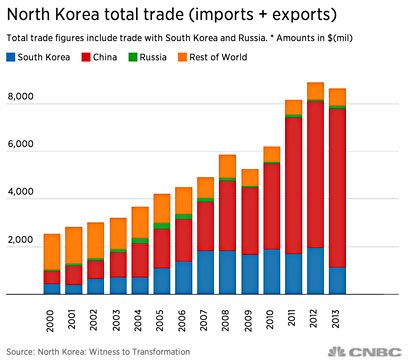

actually worth 50 grand a year? Dan Drezner thinks the whole idea is ridiculous, and he’s willing to  This means that when the United States wants to pressure Pyongyang, it has limited options as long as Chinese support of the regime remains strong. But how long will that support last? Over the weekend, Jane Perlez of the New York Times reported that it

This means that when the United States wants to pressure Pyongyang, it has limited options as long as Chinese support of the regime remains strong. But how long will that support last? Over the weekend, Jane Perlez of the New York Times reported that it