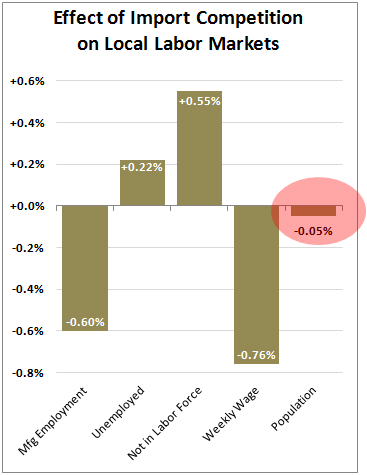

What’s been the impact of Chinese manufacturing on US employment? A recent paper by David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson adds it up like this:

What’s been the impact of Chinese manufacturing on US employment? A recent paper by David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson adds it up like this:

Had import penetration from China not grown after 1999, there would have been 560 thousand fewer manufacturing jobs lost through the year 2011….Direct plus the indirect input-output measure of exposure increases estimates of trade-induced job losses for 1999 to 2011 to 985 thousand workers in manufacturing, and to 2.0 million workers in the entire economy….Net impact of aggregate demand and reallocation effects imply that import growth from China between 1999 and 2011 led to an employment reduction of 2.4 million workers.

This amounts to direct effects of about half a million jobs, and total effects of 1 million manufacturing jobs and 2.4 million total jobs since 1999—a little less than 2 percent of all US jobs. This is a substantial number, but keep in mind that it was the result of a truly unprecedented explosion of Chinese activity: their share of global manufacturing activity skyrocketed from 5 percent to 25 percent in only 20 years. In the past half-century, no other change in bilateral trade has been even a fraction as significant.

The authors suggest that there were two main causes of China’s manufacturing success. The first, of course, is that China had a large pool of low-cost workers. The second was the accession of China to the WTO in 2001, which had forced the Chinese government over the previous decade to enact changes that made their economy considerably more efficient. So “free trade” gets the blame in one sense, but not in the sense of a direct deal between the US and China. Basically, China had to adapt to the modern global trade regime, and this compelled a wide range of economic reforms that were, in the end, good for them.

But there’s more to the story. The US labor market adjusted poorly to this competitive sea change, primarily for two reasons. The first was our decision to accommodate the Chinese manufacturing boom not with increased exports in other sectors, but with a growing trade deficit. The second was the apparent unwillingness of US workers to move when they lost their jobs:

Contrary to the canonical understanding of U.S. lab or markets as fluid and flexible, trade-induced manufacturing declines in [commuting zones] are not, over the course of a decade, largely offset by sectoral reallocation or labor mobility. Instead, overall CZ employment-to-population rates fall at least one-for-one with the decline in manufacturing employment, and generally by slightly more.

Contrary to the canonical understanding of U.S. lab or markets as fluid and flexible, trade-induced manufacturing declines in [commuting zones] are not, over the course of a decade, largely offset by sectoral reallocation or labor mobility. Instead, overall CZ employment-to-population rates fall at least one-for-one with the decline in manufacturing employment, and generally by slightly more.

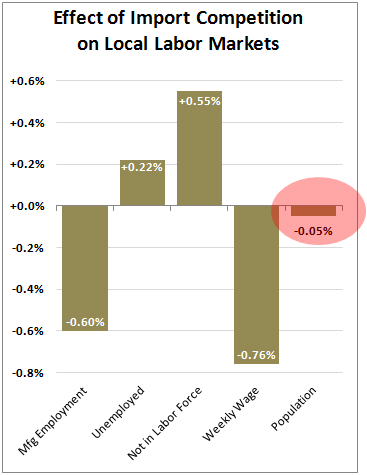

The chart on the right tells the story. The effects of import competition are frequently local rather than national, and on average produce lower manufacturing employment and lower wages, along with higher unemployment. But out-migration from affected areas is nearly zero. Workers who are affected by an import shock stay where they are instead of moving to greener pastures.

Why? It’s hard to know how to allocate blame here. On the one hand, you have the big macroeconomic effect of a growing trade deficit, which is outside the control of individual workers. On the other hand, you have an unwillingness to move when the local economy tanks, which is very much within the control of individual workers. Taken together, it’s almost a conspiracy to give up. At a national level, we shrug and simply accept a trade deficit. At an individual level, we shrug and accept that no jobs are available anywhere.

It’s mostly a moot point now. The huge Chinese growth boom is largely over, and it’s unlikely anything similar is going to come along soon. New trade deals—regardless of whether you like them or hate them—simply don’t have a very big impact on anything. Their effects can be measured in tenths of a percentage point 20 years down the road. Still, it’s hard not to wonder why we collectively decided to do next to nothing to respond to the Chinese boom during the 90s and aughts.

From House Speaker Paul Ryan, talking about his view of tax reform:

From House Speaker Paul Ryan, talking about his view of tax reform:

told me. “Sometimes we’re going to get what we want precisely because we are sharing in the agenda.”

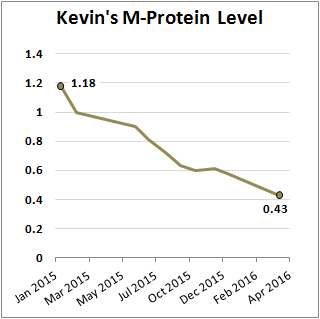

told me. “Sometimes we’re going to get what we want precisely because we are sharing in the agenda.” Not much to report this month. My M-protein level—a proxy for the level of cancerous plasma cells in my bone marrow—is down from 0.48 in February to 0.43 in March. That’s not a big drop, but it’s a drop, and anything moving in the right direction is good news. Apparently the evil dex is reluctantly doing its job.

Not much to report this month. My M-protein level—a proxy for the level of cancerous plasma cells in my bone marrow—is down from 0.48 in February to 0.43 in March. That’s not a big drop, but it’s a drop, and anything moving in the right direction is good news. Apparently the evil dex is reluctantly doing its job. What’s been the impact of Chinese manufacturing on US employment? A recent paper by David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson

What’s been the impact of Chinese manufacturing on US employment? A recent paper by David Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon Hanson  Contrary to the canonical understanding of U.S. lab or markets as fluid and flexible, trade-induced manufacturing declines in [commuting zones] are not, over the course of a decade, largely offset by sectoral reallocation or labor mobility. Instead, overall CZ employment-to-population rates fall at least one-for-one with the decline in manufacturing employment, and generally by slightly more.

Contrary to the canonical understanding of U.S. lab or markets as fluid and flexible, trade-induced manufacturing declines in [commuting zones] are not, over the course of a decade, largely offset by sectoral reallocation or labor mobility. Instead, overall CZ employment-to-population rates fall at least one-for-one with the decline in manufacturing employment, and generally by slightly more. be the primary attack from Republicans?

be the primary attack from Republicans? journalist to achieve anything close to gender balance in her reporting.

journalist to achieve anything close to gender balance in her reporting. Max Boot is decidedly impressed with Vladimir Putin—

Max Boot is decidedly impressed with Vladimir Putin—