David Dayen brings hope to my withered soul. A few days ago he described a Senate hearing that seemingly brought both liberals and conservatives together on a subject close to my heart: antitrust law. “The fact that both parties want the government to stop monopolies,” he says, “could finally force the agencies to get aggressive and protect the economy”:

We have four airlines serving 80 percent of all passengers. We have four cable and Internet companies providing most of the nation’s cell-phone and television service. We have four big commercial banks, five big insurance companies (only three if two proposed mergers go through this year), and a handful of producers selling every major consumer product. Even when you think you have a choice, like in the array of online travel-booking sites, two companies (Expedia and Priceline) own all the subsidiaries.

….Senator Mike Lee, the Utah Republican who chairs the subcommittee, worried that the agencies lack the resources to deal with the merger wave. Ranking member Amy Klobuchar, the Minnesota Democrat, questioned the “conduct remedies” agencies use in lieu of blocking mergers—for instance, forcing the merged company to sell off retail outlets or business lines to maintain competition.

….Iowa Republican Chuck Grassley brought up consolidation in the market for seeds, and how that creates issues in the food-supply chain—if one set of seeds is tainted and a monopoly controls seed distribution, the consequences of safety hazards  magnifies. Al Franken, the Minnesota Democrat, expressed concern about “platform monopolies”—Internet giants like Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon, who “use their positions … to stifle competition and inhibit the free flow of ideas.”

magnifies. Al Franken, the Minnesota Democrat, expressed concern about “platform monopolies”—Internet giants like Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon, who “use their positions … to stifle competition and inhibit the free flow of ideas.”

Over the past few decades, America has undergone a sea change in antitrust law. It’s now all about “consumer welfare”—which means, in practice, that big mergers are fine as long as the mergees can make a credible case that the combined entity will be good for consumers. You will be unsurprised to learn that high-powered marketing departments are very good at collecting data to show exactly that, and that high-powered attorneys are extremely good at turning this data into bulletproof legal arguments. The result is that very few mergers are ever turned down.

But this siren call has led us down a long, blind alley. It turns out that in the short term, plenty of big mergers really can be good for consumers. In the longer term, though, very few are. All the promises and regulations in the world will never change the fact that once a market is dominated by three or four huge corporations, competition becomes flabby and listless. In markets with low barriers to entry, this isn’t too big a deal. New entrants will build new markets regardless. But in markets with high capital costs or other barriers to entry, it can cause unhealthy and needless stagnation.

We’d be better off returning to an older, cruder rule: ensuring that there are plenty of competitors in every market and refusing to allow any single company to become too dominant. As near as I can tell, there’s a real tipping point around the number three or four. If a market is dominated by four companies or less, that’s when it starts to wither.

Even a single company can make a big difference. Take a look at the cell phone market: T-Mobile tried several times to engineer a merger with another provider, but couldn’t get approval. So instead they adopted a strategy of genuine competition, hoping that lower prices and better features would upset the market and bring them new customers. This has had a huge impact on the mobile phone industry, and it never would have happened if the number of providers had made that final, fatal slide from four companies to three.

Needless to say, even a crude market share rule doesn’t make things simple. You’ll still have arguments over what counts as a single market (online advertising or the entire advertising industry?). You’ll have arguments over just how big a single company should be allowed to get (30 percent share or 50 percent share?). You’ll have industries where it’s not easy to have lots of competitors. And you’ll have some industries where the returns to scale to are so potent that small companies just flatly can’t compete.

There’s no easy panacea. But “consumer welfare” is an open invitation to thousand-page regulatory filings that dive deep down a rabbit hole and never come up for air. A smart team of attorneys can make a credible case that just about anything is good for consumers if you look at it in just the right way. A simple market dominance test, however, isn’t so easy to game. It may not be perfect, but it would be a lot better than what we have now.

Competition is the core engine of capitalism. If you have plenty of it, you can make do without a lot of other regulations. But once you allow competition to wither, there’s little choice left. The remaining companies have lots of market power, lots of political power, and not much desire to see markets get disrupted. They have to be heavily regulated—and even that won’t work very well. You just end up in an endless game of cat and mouse.

Why bother? The federal government should do its best to ensure that markets have plenty of competition, and then it can afford to get out of the way and regulate fairly lightly. Other companies will do their work for them. What’s not to like?

With opioid painkiller addiction now at epidemic levels, the CDC has finally issued

With opioid painkiller addiction now at epidemic levels, the CDC has finally issued  magnifies. Al Franken, the Minnesota Democrat, expressed concern about “platform monopolies”—Internet giants like Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon, who “use their positions … to stifle competition and inhibit the free flow of ideas.”

magnifies. Al Franken, the Minnesota Democrat, expressed concern about “platform monopolies”—Internet giants like Facebook, Google, Apple, and Amazon, who “use their positions … to stifle competition and inhibit the free flow of ideas.” they thought they could

they thought they could  has taken away lots of good, semi-skilled jobs. Illegal immigration has taken away the unskilled jobs. Culturally it feels like traditional values are under attack. Etc.

has taken away lots of good, semi-skilled jobs. Illegal immigration has taken away the unskilled jobs. Culturally it feels like traditional values are under attack. Etc.

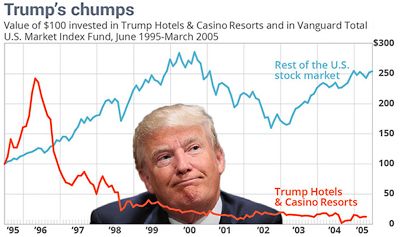

$100 million more than analysts thought it was worth…sending the company’s stock into a nosedive from which it never recovered.

$100 million more than analysts thought it was worth…sending the company’s stock into a nosedive from which it never recovered.