Kerry Washington as Anita HillFrank Masi

Director Rick Famuyiwa remembers watching the confirmation hearings for Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas as a freshman at the University of Southern California. He was interested in politics, and in scrutinizing the man who would replace the retired civil rights crusader Thurgood Marshall on the high court. The hearings “always stuck with me,” he says. Nearly a quarter century later, the script for the forthcoming HBO film, Confirmation, by Erin Brockovich screenwriter Susannah Grant, “just completely took me in,” Famuyiwa told me. He was struck by how many of the details America seemed to have forgotten.

The Nigerian-American director, raised near Los Angeles, was fresh off a breakout success with his coming-of-age comedy, Dope, about a black nerd from Ingleside who sets his sights on Harvard. Confirmation was about as far away from Dope as Famuyiwa could get. Yet some of the story’s elements were familiar, like the intersection of race and politics. He also explored that theme in 2007’s Talk to Me—wherein Don Cheadle plays Ralph Waldo “Petey” Greene Jr., an ex-con turned DC radio personality who helped keep the city calm the night MLK Jr. was assassinated.

Confirmation‘s air date—Saturday, April 16—is excellent timing given the constitutional cage-fight over President Barack Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to replace Antonin Scalia on the high court. Famuyiwa’s film looks back at one of the nastiest political fights of the last century—and one that has had a lasting impact on gender interactions in the workplace. Here’s a quick recap: In July 1991, President George H.W. Bush nominated Thomas to replace retiring Justice Marshall. Deep into the hearings, Anita Hill, a religious, reserved Oklahoma law professor who’d worked under Thomas at the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission and the Department of Education, was called upon to testify. Her public charges of sexual harassment against her former boss threw a bomb into DC politics that left few unscathed.

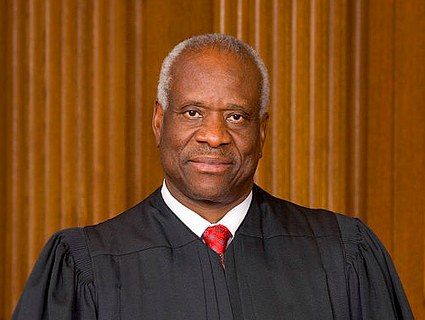

Famuyiwa plays things pretty straight, despite complaints from some of the politicians portrayed. Kerry Washington, of Scandal fame, plays Hill, and Wendell Pierce, best known as Detective “Bunk” Moreland from The Wire, portrays a stoic Thomas. But in Famuyiwa’s telling, Hill and Thomas are almost peripheral characters. The big players are the members of the Senate Judiciary Committee, whose infighting and backstabbing make up the bulk of the action.

Vice President Joe Biden, played by Greg Kinnear, will not be too pleased with this blast from the past. It recalls Biden’s less-than-stellar performance as the committee chair who ineptly let his GOP colleagues eviscerate Hill with thinly sourced evidence, and refused to let other witnesses, including women with similar allegations, to testify on Hill’s behalf.

Former Sen. Alan Simpson (R-Wyo.), who saw a script of the film that was not yet final, raised the possibility of legal action. So has former Sen. John Danforth (R-Mo.), Thomas’ longtime patron and mentor. Danforth’s ruthlessness comes across in a scene in which his character consults with a psychiatrist who implies it would be possible to say Hill was suffering from “erotomania”—a delusion that Thomas had been in love with her.

The conclusion of Confirmation is no more satisfying, alas, than that of the real-life hearings, which elevated Thomas to the Supreme Court on a 52-48 vote, yet never really resolved who was telling the truth. “I didn’t want to try to take that point of view,” Famuyiwa explains, “because it would be a fool’s errand.”

Mother Jones: So much of the story is people talking—in offices, in Senate offices, phone calls. How did you hope to dramatize that? I mean, it’s a good thing this happened before email, because—

Rick Famuyiwa: It would have all been email! Exactly. That was the biggest challenge. It was also just embracing the fact that it was going to be procedural, and that it was going to be a lot of talking heads.

MJ: You did actually manage to work in a car chase of sorts, with Hill being pursued from the DC airport by TV trucks.

RF: We were excited to get outside! By the time she arrived, there had been such a buildup of who she was and her impact on the hearings. There was a huge attack on her as she descended into DC. Obviously there are creative licenses that you take as a filmmaker. At the time, there were these paparazzi chases—Princess Diana. We wanted to be representative of the beginning of that hot, 24-hour news feeding frenzy.

MJ: Hill and Thomas seem almost secondary in the film, but the senators are really front and center. Was that intentional?

RF: Yes, in some ways. It was titled Confirmation very purposefully. I wanted the film to be about that process—about how Judge Thomas and Anita Hill were thrown into a situation that was difficult for anyone to navigate, no matter what the truth was. It’s hard to know what the truth is.

I really wanted it to be about the human reaction—whether you’re Judge Thomas and you’re reaching the pinnacle of your career and you see it about to fall away from you, or you’re Anita Hill and you know that injecting yourself into this process probably means coming under attack and possibly having your life and career changed in the process. Both of them had to face this. They were similar in many ways. There’s just a lot of interesting plot turns beyond who told the truth.

MJ: There was one scene in which NPR Supreme Court reporter Nina Totenberg* calls Hill. Was that really Totenberg?

RF: [Laughs.] Unfortunately, no. There is a strict NPR policy in terms of having their reporters in films and television—unless they are recreating the actual broadcast. That was a sound-alike.

MJ: I hear some of the senators you portrayed are pretty upset. Especially John Danforth, who was way creepier in the film than I remember him.

RF: That wasn’t the intention. These are people who believed in Clarence and believed in his innocence and believed he was being wrongly accused and railroaded by special interests. In that case, you try to protect your friend and colleague. Things look different to you now then they did then. You look back on it with a lens and you go, “Wow, maybe that didn’t look so great.” A lot of this stuff was researched, and many accounts came from books, including [Danforth’s]. We were trying to be fair to everyone involved knowing that these were issues that a lot of people wouldn’t want to revisit.

MJ: As a black man, did you feel sympathy for Clarence Thomas?

RF: I think you feel for anyone who’s going through something like this. I can understand being in such a public place and having your intimate private life examined. These were two very accomplished black people who were basically on a national stage calling each other a liar and going after each other. At the time, there was a notion that because he was black and she was black that race didn’t factor into the overall experience. But as we all know, race is central to all of our experiences. Anita Hill has changed the history of how we deal with each other in the workplace. But it also was an interesting episode in how race and the history of race converged in this moment and got used and twisted and interpreted in all kind of ways. I didn’t want to shy away from that.

MJ: This film is pretty different from Dope. Is there anything that ties them together?

RF: [Laughs.] If there is a thread, it is the perception of how race changes perception and points of view. Obviously, the big turning point in the hearing was Clarence Thomas’ high-tech lynching speech, where race was thrown right in there.

MJ: Okay, I know we’re out of time, but before you go I have to ask: Whom did you personally believe?

RF: I don’t know if I can definitively say anything about that. My perspective has changed and morphed. That’s why I felt like that wouldn’t necessarily be the way to approach the film. I’ll give you that non-answer.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelled the last name of NPR reporter Nina Totenberg.