Photo: Corbis

Listen to Ben Temchine interview Bernice Yeung

on a weekday morning last August, I sat in the visiting room of the Coxsackie Correctional Facility in upstate New York gazing at the elaborate concertina wire that surrounds it. After a long wait, a metal gate clanged shut and in walked Emmanuel Constant, founder and former leader of the Front for the Advancement and Progress of Haiti (fraph), an organization linked to the rapes and murders of pro-democracy activists in Haiti during the early 1990s. He smiled pleasantly and extended his hand for a firm shake.

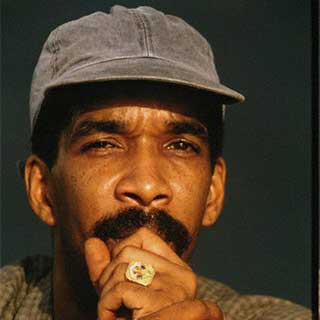

I’d seen footage of Constant back in his heyday sporting tailored suits before a throng of microphones and firing up rallies with a raised fist. Now he appeared somber in state-issued forest-green slacks and a yellow polo shirt. He had the same long, equine face and pronounced jowls, but at 51, his short Afro was flecked with gray and he wore drugstore-style glasses. Working the media is perhaps Constant’s greatest skill—he is personable, charming, even likable. But he wasn’t ready to trust a surprise visitor, he said, so we made small talk, chatting about the public-speaking and memoir-writing classes he’d taken prior to lockup and about his jailhouse reading of John Grisham and self-help books. Fellow inmates were teaching him to trace cartoon characters onto envelopes to bring mail recipients a little cheer—some, he added, decorated scarves purchased from the commissary as gifts for faraway girlfriends. It was just over an hour into our meeting that Constant’s eyes began to water. “I hate to tell you this,” he said, composing himself, “but I feel that all of this is quite unfair.”

Emmanuel “Toto” Constant is heir to a violent legacy. He was born in 1956, one year before François Duvalier—Haiti’s brutal dictator for nearly 14 years—took power. His father was Duvalier’s chief of staff and the men, Constant says, would hold strategy meetings in his childhood bedroom as he slept. Decades later, some of his family’s political allies helped engineer a military coup that drove Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the country’s first democratically elected president, into exile in Venezuela.

The 1991 coup brought crippling international sanctions. Inspired by a dream in which he says he saw his late father, Constant resolved to fight the embargo. He scoffs at media reports that the cia fronted him guns and cash to launch his anti-Aristide organization. (The agency declines to comment.) No, he launched fraph in mid-1993 to help the poor. Its first event, Constant claims, was a food drive. “I let go 100 white pigeons in a show of peace.”

At the time, the United Nations was brokering a deal with the junta to let Aristide resume his presidency in October 1993. But when the Clinton administration, ostensibly to quell unrest in advance of Aristide’s return, sent the uss Harlan County to Port-au-Prince that month, Constant and members of his nascent organization staged a noisy protest at the docks. The warship retreated amid great fanfare. “I put the White House in a position where they could not go ahead with what they wanted,” Constant brags. With tacit support from Haiti’s military, fraph opened hundreds of outposts, and Constant seized the limelight, holding regular radio addresses and dramatic press conferences and rallies where he denounced the embargo and assailed Aristide for exacerbating class divisions. But human-rights watchdogs say the group was modeled after the Tontons Macoutes, Duvalier’s personal police force, which shook down, tortured, and killed the dictator’s political opponents.

According to declassified cia reports, fraph conducted violent attacks, ran extortion rackets, and became a “major perpetrator of abuses.” The Organization of American States has reported that members of Constant’s group, the army, and the police terrorized Haitians “with complete impunity.” Victims described gang rapes by as many as five fraph members while their young children were forced to watch. “Supporters of Aristide were severely intimidated, and in some cases, killed,” says John Shattuck, assistant secretary of human rights under President Clinton.

Constant insists he is blameless. “They said that my popularity came because I was killing people,” he told me. “But no political leader ever had the [media] exposure I had. And some people have never forgiven me for it.”

Those close to him say the Constant they know isn’t capable of savagery. “Emmanuel is really a wonderful man,” says his former girlfriend, mother of his toddler son. “And he is very sensitive. More sensitive than people know.” A friend from Constant’s youth claims Louis Jodel Chamblain, fraph‘s second in command, was the real hatchet man. “The Toto I know is a playboy,” he says. (Constant’s ex says he has seven children “that he knows of ” by three mothers.)

But the Toto who revealed himself in letters following our last jailhouse visit seemed more of a manipulator, a man desperate for public sympathy, which even his closest supporters won’t provide. His friend and ex-girlfriend insisted their names stay out of print, and Constant complained that letters to his siblings have gone unanswered. When I called one of his uncles, a retired bishop, at his home in Gonaives, Haiti, he said he had “no interest in anything Emmanuel Constant,” and hung up.

In his letters to me, Constant proclaimed his innocence and professed loneliness and frustration. “I am fighting for my life, against very powerful people,” he wrote last August. “I feel alone in my struggle.” Later came the “scarf,” really a white cotton handkerchief, on which he’d traced Betty Boop and Tweety Bird in colored marker.

Constant has had more success finessing America’s political system. His first encounter with U.S. courts came after Aristide returned to Haiti in the fall of 1994, prompting fraph to disintegrate and its leaders to flee. Word soon spread among New York’s Haitian Americans that Toto Constant could be spotted chain-smoking Newports on his aunt’s porch in Queens. When the community protested, immigration authorities yanked Constant’s visa and threw him in a Maryland detention cell.

Not to be defeated, Constant arranged an exclusive interview with 60 Minutes, telling Ed Bradley he’d been a paid cia informant prior to launching fraph. He then filed a $50 million wrongful-detention lawsuit against the United States and argued that his incarceration kept him from running for office in Haiti. Within a few months, the case settled—Constant dropped his suit and was allowed to stay in America. This sparked more angry protests by local Haitians, who suspected their nemesis caught a break in exchange for keeping quiet about his U.S. government ties.

Back in Queens, Constant dabbled in this and that, but bad publicity inevitably derailed his business attempts—in August 2000, for instance, a community protest cost him a job as a real estate agent. Going home was out of the question: That November, Constant and 53 other military and paramilitary personnel were tried in Haiti for the 1994 Raboteau Massacre—a raid of an Aristide stronghold that led to at least eight deaths and dozens of injuries. After a six-week jury trial overseen by the United Nations, Constant was convicted in absentia and sentenced to life in prison. (Haiti’s Supreme Court quashed the sentences in 2005 over a trial technicality.)

The Clinton administration again declined to deport him, so Constant moved on, setting up a real estate business with his then-girlfriend Raphaelle Turnier. He settled into American life, showing up for ab workouts at the Learning Annex’s Midtown campus and tae kwon do classes in Long Island. He took his kids on trips to Disney World and danced the night away to house music in after-hours clubs.

But while walking in Manhattan one afternoon in 2004, Constant heard someone call his name. When he turned around, a man handed him a subpoena. Three women who’d fled to the States were alleging they’d been gang-raped in Haiti years before by members of his organization. (One bore a child as a result, according to courtroom testimony.) Constant ignored the civil summons, and in 2006 the judge ordered him to pay the women a total of $19 million. He has since challenged the judgment, and the plaintiffs haven’t seen a penny.

Constant’s latest troubles started around early 2003, when investigators from the state attorney general’s office began poking into suspicious dealings by D&M Financial, a New Jersey-based lender. With documents and cell phone taps, they determined that a group of unlicensed appraisers and unscrupulous lawyers, real estate agents, and mortgage brokers affiliated with the bank were misrepresenting the value of targeted properties to secure loans they never intended to repay.

An informant pointed them to Constant, who managed a Long Island D&M branch. Curious, the investigators dug up old news clips, the 60 Minutes piece, and filings from his past cases. “He was not being pursued because of his background,” clarifies a source involved in the investigation. “He’s just another mortgage-fraud crook.”

According to the indictment, Constant’s role was to recruit straw buyers and doctor their records so they’d seem like good loan candidates. He often targeted Haitian Americans, including one cash-strapped cabbie his friend met at a barbecue. In July 2006, police arrested Constant at his girlfriend’s Brooklyn apartment. He was charged with forgery and grand larceny and ordered held on $500,000 bail. “I was humiliated,” he recalled of that day. “I felt like I was going to lose my life and everything was going down the drain.”

In the end, the attorney general extended a deal: Constant would plead no contest and do one to three years in state prison, part of which he’d already served. But his past finally caught up with him: The non profits that had sued on behalf of the rape victims launched a letter-writing campaign on the eve of his Brooklyn sentencing—they worried, in part, that Constant would be deported to Haiti and escape justice there.

Barraged with more than 800 letters and faxes detailing fraph‘s abuses, Judge Abraham Gerges rejected the plea last May. In November, the judge proffered a new deal: three to nine. Feeling bullied, Constant chose a jury trial, risking the 15-year max. “I’m a political prisoner,” he lamented. “Mortgage fraud! I should have gotten a slap on the wrist, and instead they put me in jail for political reasons.”

He’d like to think so, but his pursuers preferred the original plea deal over a trial. “No matter how good your evidence is, it could fall apart, and it would be embarrassing to not get a conviction with a man like Emmanuel Constant,” says the inside source. As for the political prisoner bit: “I’m agnostic as to who he was in Haiti.”

In any case, politics are not expected to play a role in the trial, which at press time was slated for late April. “It’ll be a long, boring trial,” predicts Constant’s attorney, Samuel Karliner. “It’s going to be bank managers testifying during most of it.”

Indeed, what Constant seems to fear most isn’t the jail time so much as irrelevance—that the founder of one of Haiti’s most feared organizations will be reduced in stature to a petty criminal. He believes he may yet play a prominent role in Haiti’s future. “I can even be the president, the prime minister,” he told me at one point before pausing in a fleeting moment of self-awareness. “It’s strange to be locked up in prison upstate and talk about being president of Haiti, right? It’s strange.”

Then, just as quickly, the glint in his eye returned. “Strange meaning it’s happened before. That people have come from jail to become leaders of their country.”