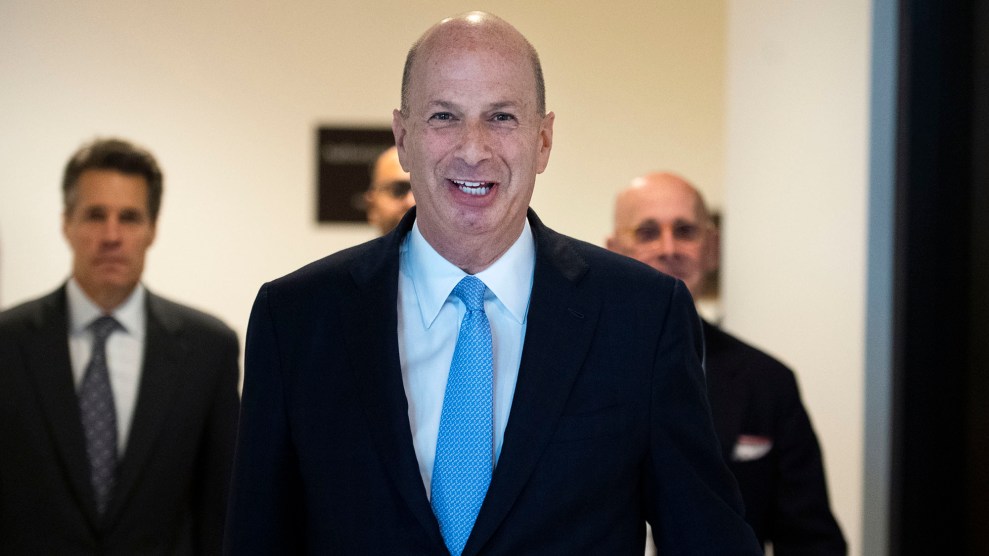

Gordon Sondland arrives on Capitol Hill for his Ukraine scandal deposition.Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call via Getty

Gordon Sondland would not have been any reasonable person’s first choice for a senior State Department post. Or their 20th choice. Before he found himself at the center of the Ukraine scandal, Sondland was a hotel magnate with zero relevant expertise or diplomatic experience. President Donald Trump nominated him to be ambassador to the European Union largely because of his status as a GOP megadonor who contributed $1 million to Trump’s inauguration.

Rewarding political supporters with ambassadorships they aren’t qualified for is a bipartisan tradition dating back centuries. But Trump has elevated the practice to new heights—a disturbing development at a time when experienced staffers are leaving the State Department in droves.

Most ambassadors are career foreign service officers, highly trained professionals who have worked their way up through the diplomatic ranks. But a significant minority are so-called “political ambassadors” who come from outside the diplomatic corps—generally a mishmash of campaign donors, ex-lawmakers, and retired military officers. Under President Obama, these political ambassadors made up 30 percent of total appointees, according to a paper by Ryan Scoville, an associate professor at Marquette University Law School. Under Trump, that figure has ballooned to more than 40 percent, the highest number in nearly eight decades.

Presidents tend to appoint political ambassadors early in their terms, so Trump’s percentage could fall over time. Still, his picks have been uniquely unqualified—even when compared to the political ambassadors chosen by other presidents. “Not only are these people more common, but they’re less qualified than their predecessors,” Scoville told me. Twenty-six percent of Ronald Reagan’s political ambassadors had at least some experience in the region where they were sent, according to Scoville’s research. For Trump’s nominees, that figure is just 5 percent. Nearly every other metric—knowledge of the country’s primary language, foreign policy experience, prior leadership positions—supports the same conclusion: Trump’s diplomatic nominees are less qualified than their predecessors by a significant margin.

With more of his donors receiving top diplomatic assignments, Trump has broken precedent in another significant way. Normally, geopolitically sensitive postings in places like the Middle East are reserved for experienced envoys. But last year, Trump picked John Rakolta, a Michigan businessman with no relevant experience, to lead the embassy in the United Arab Emirates, an important regional ally that for much of the past four years has been embroiled in the bloody conflict in Yemen. Rakolta had given $250,000 to Trump’s inaugural committee.

That’s far from Trump’s only bizarre diplomatic nomination. His ambassador to Hungary, David Cornstein, is a jewelry magnate and member of Trump’s West Palm Beach golf club who is apparently fond of stripping down to his underwear to nap alongside President Viktor Orban during their flights together. Cornstein has uncritically supported Orban, even as the right-wing leader has grown increasingly hostile to civil liberties and evicted the American-supported Central European University from Hungary. Doug Manchester, who gave $1 million to Trump’s inaugural committee, recently withdrew his bid to become ambassador to the Bahamas—two years after mistakenly asserting during his confirmation process that the island nation was part of the United States.

These oddball picks, coupled with a devastating hiring freeze during Trump’s first 16 months in office, have damaged morale and pushed veteran foreign service officers into an early exit from government employment. “We’ve had a wave of retirements of our senior people,” Eric Rubin, former ambassador to Bulgaria and president of the American Foreign Service Association, told me. The problem has been compounded by Trump allies’ efforts to undermine career diplomats like Marie Yovanovitch, who was abruptly recalled from her post as ambassador to Ukraine in May. She later told House investigators that “people with clearly questionable motives”—including Trump’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani—smeared her reputation, paving the way for her ouster.

Trump’s critics have taken notice. Elizabeth Warren vowed in June that as president, she would not give diplomatic posts to wealthy donors and blasted Trump for letting the State Department wither through “a toxic combination of malice and neglect.”

In recent weeks, Sondland has emerged as the poster child of the diplomatic spoils system because of his role in the impeachment inquiry. As ambassador to the EU—an entity that does not include Ukraine—he somehow became a key participant in what Bill Taylor, the top US envoy in Kyiv, called a “highly irregular” channel of outreach to the Ukrainian government. The goal of this shadow diplomacy, led by Giuliani, was to get Ukraine’s leader to issue a statement saying it was investigating Trump’s political enemies, including Joe Biden and his son, Hunter. In a September meeting with an adviser to the Ukrainian president, Sondland made clear that US military aid would be contingent on those probes. “I said that resumption of the US aid would likely not occur until Ukraine provided the public anticorruption statement that we had been discussing for many weeks,” Sondland recently told lawmakers—a fact that he had omitted from the original version of his testimony.

Various national security officials have blasted Sondland’s meddling. “I stated to Ambassador Sondland that his statements were inappropriate, that the request to investigate Biden and his son had nothing to do with national security,” Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Vindman, who serves on the national security council, told House investigators. “I am not part of whatever drug deal Sondland and [acting White House chief of staff Mick] Mulvaney are cooking up,” then-national security adviser John Bolton said, according to one of his colleagues.

Sondland’s admissions have proved extremely damaging to Trump—something Trump seems to have recognized. As recently as last month, the president called him a “really good man and great American” in a tweet. But by Friday, Trump had firmly driven a bus over Sondland’s back. “I hardly know the gentleman,” Trump told reporters.

House Republicans have followed Trump’s lead, attempting to portray Sondland, Giuliani, and Mulvaney as the true masterminds of the Ukraine strategy. Despite the fact that Trump, both publicly and privately, endorsed the campaign to pressure Ukraine, his defenders claim that Sondland was acting without the president’s knowledge or approval.

Sondland has now become as useful to Trump as Michael Cohen, Jeff Sessions, or any of the other erstwhile allies who quickly turned into objects of his wrath. Sondland testified last month that he was “disappointed by the president’s direction that we involve Mr. Giuliani” in the national security process, saying that in his view, “the men and women of the State Department, not the president’s personal lawyer, should take responsibility for all aspects of US foreign policy toward Ukraine.”

Loyalty has long been the currency underpinning the donor-to-ambassador pipeline. But Sondland—out of fear for his own well-being or, perhaps, an inclination to finally tell the truth—showed there are limits to what a plum diplomatic posting can buy.

Listen to Washington, DC Bureau Chief David Corn describe the outrageous partisan theatrics in the impeachment room, and the mounting evidence against Donald Trump, in the latest episode of the Mother Jones Podcast: