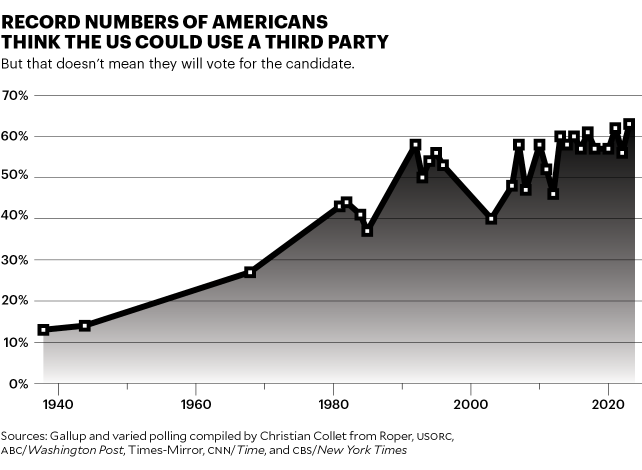

Frustrated by the two-party system? Polling shows you’re not alone, with more Americans than ever supporting the idea of a third party. But the winner of November’s presidential election will be either Biden or Trump, and voters weighing other candidates need to consider if a protest vote to end the duopoly might instead help end our democracy. In the May+June 2024 issue, we examine the past and present of third-party outsiders, and how they could upend this year’s race. You can read all the pieces here.

In the summer of 2000, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., a scion of the Democratic Party dynasty, took time out of his schedule as an environmental attorney to write an op-ed for the New York Times. In the piece, Kennedy hailed consumer advocate Ralph Nader as his “friend and hero,” but he lambasted him for mounting a third-party run for president. Nader could “siphon votes” from Vice President Al Gore, who was running against Texas Gov. George W. Bush, Kennedy warned, saying it was “irresponsible” for Nader to argue that there was “little distinction” between the Democratic and Republican nominees. A vote for Nader, Kennedy asserted, “is a vote for Mr. Bush” and for what he considered a disaster: the Republicans’ anti-environment agenda.

That was then.

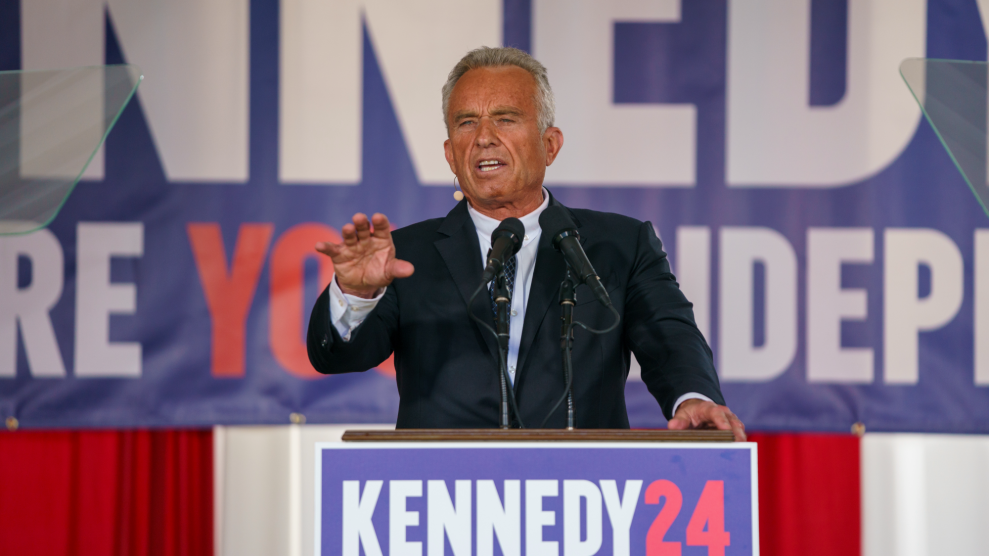

Twenty-four years later, now an anti-vaxxer and conspiracy theorist, Kennedy has broken with the Democratic Party and is running for president as an independent. He insists that unlike Nader, he’s no spoiler, and he dismisses the notion that his presence in the race will help either former President Donald Trump or President Joe Biden. Political analysts are uncertain which candidate will benefit more from Kennedy’s campaign. The Kennedy brand could hold appeal for some Democrats, but his paranoia-drenched attacks on the public health community could also be catnip for Trump voters. “I think Americans should have a choice,” Kennedy told NBC News, “that they shouldn’t be forced to choose the least of two evils.”

Democratic and Republican political pros have good cause to be jittery about how third-party or independent presidential candidates might impact this race. The reason is simple: The last two elections have been decided by extremely narrow margins in a tiny number of states. The odds are strong that this year’s contest will be similarly close. If so, there’s potential for one or more of the third-party or independent contenders already in the race—Kennedy, Green Party leader Jill Stein, or author and professor Cornel West—to influence the outcome by drawing a small slice of voters from Biden or Trump. Given the circumstances, it is far easier to view these outside presidential bids as potential threats to a major candidate rather than as well-intentioned movements to expand the horizons of American politics. That is especially true considering that an outsider campaign can be weaponized by other political players pursuing quite different agendas than those of the third-party candidates themselves. With the 2024 election shaping up to be a referendum on American democracy, a minor candidate might end up helping to determine the future of the republic.

For decades, voices across the political spectrum have railed against the party duopoly. Occasionally, a serious independent or third-party presidential candidate has emerged, but none has won a presidential contest—or even come remotely close. Only a few insurgents have significantly shaped the final outcome. Notably, Theodore Roosevelt’s post-presidency run in 1912 under the banner of the Progressive Party (a.k.a. the Bull Moose Party) essentially doomed the reelection campaign of Republican President William Howard Taft and helped New Jersey Gov. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat, win the White House.

Other third-party presidential candidates have fared worse but still gained notoriety and attention for their ideological agendas. Socialist Eugene Debs was on the ballot in five presidential races between 1900 and 1920. (During his last bid, he ran while imprisoned after being convicted of sedition for urging resistance to the military draft.) Progressive Wisconsin Gov. Robert La Follette sought the presidency in 1924. South Carolina’s white-supremacist governor, Strom Thurmond, was the candidate for the States Rights Democratic Party (otherwise known as the Dixiecrats) in 1948. Twenty years later, Alabama Gov. George Wallace campaigned as the head of the pro-segregationist American Independent Party. Businessman Ross Perot’s independent 1992 bid drew 19 percent of the vote—the best outing by an outside-the-system candidate since Roosevelt. To this day, political scientists argue about whether Perot pickpocketed more votes from Bill Clinton or George H.W. Bush.

The Nader effect was clearer. In 2000, running on the Green Party ticket, he pulled in 22,198 votes in New Hampshire, more than three times the 7,211 vote lead George W. Bush had over Gore. In Florida, where Bush edged out Gore by 537 votes, Nader bagged 97,488. While impossible to prove, it is a reasonable hypothesis that had Nader not been on the ballot, Gore, a noted environmentalist, would have picked up enough of those Nader votes to win. (Also complicating that election was ultra-conservative commentator Pat Buchanan’s Reform Party; his vote total in Florida was boosted by a poorly designed ballot in Palm Beach County that likely cost Gore more than 2,000 votes.) Had Gore triumphed in 2000, you can imagine the United States taking vigorous steps to address climate change—which President George W. Bush did not—and avoiding the catastrophic invasion of Iraq that yielded the deaths of more than 4,000 American troops and more than 200,000 Iraqi civilians. In 2000, RFK Jr. was right.

During the 2016 showdown between former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Trump, Green Party candidate Jill Stein bagged 1 percent of the national vote, and Libertarian Party candidate Gary Johnson collected 3.3 percent. In key swing states such as Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, and Florida, these candidates’ combined vote totals exceeded the margin by which Trump beat Clinton. There’s no telling how many of the Stein and Johnson voters would have pulled the lever for Clinton had those other choices not been available. Stein justified her campaign by arguing Clinton and Trump were equivalent: “We have two ways to commit suicide here,” she said, “and I say no thank you to them both.”

The years since then have demonstrated just how stark the differences between those two candidates really were. The list of consequences of that election result is long and includes the overturning of Roe v. Wade and Trump inciting a mob to lay siege to the Capitol in an attempt to illegally remain in office.

The stakes are even higher this year, and outsider candidates may be better positioned to affect the outcome. “Third-party and independent presidential candidates could play a more significant role in 2024 than in most presidential elections in recent memory,” says Bernard Tamas, a political science professor at Valdosta State University and the author of The Demise and Rebirth of American Third Parties. He explains that the growth of third parties over the last 60 years is the result of “the rising contentiousness of a steadily more polarized conflict between the two major parties.” During the 2024 election cycle, the mutual hostility has escalated to the point where each party accuses the other of “subverting democracy.” The result? “This combination of high public dissatisfaction with well-known candidates could fuel a significant increase in the protest vote against both Biden and Trump,” Tamas says.

Understandably, then, the prospect of third-party spoilage is a source of dread for political strategists. For much of the past year, Democrats and never-Trumpers fretted over No Labels, a dark-money group that used millions of dollars raised from anonymous sources to win spots on state ballots for a supposed centrist, bipartisan ticket. (Mother Jones and other news organizations have revealed some of its funders; as a group, they tilt toward the GOP.) Founded by former Democratic fundraiser Nancy Jacobson—her husband is Mark Penn (once a top strategist for President Bill Clinton), who advised Trump during his first impeachment—the No Labels project was generally seen by political insiders as unlikely to succeed in running a viable candidate and widely regarded as being more beneficial for Trump than for Biden.

Democrats and other anti-Trumpers who considered No Labels something of a pro-Trump front took steps to neutralize this venture, decrying the group, challenging its petition drives, and putting pressure on prospective donors. In response, No Labels called on the Justice Department to investigate its opponents for trying to prevent it from obtaining ballot access. Meanwhile, Sen. Joe Manchin, a conservative Democrat from West Virginia and the potential No Labels candidate mentioned most often, eventually withdrew from consideration, noting that he did not want to help Trump win. That left the group with no obvious standard-bearer and the lingering question of whether it would field a surprise candidate or fizzle. Finally, in the first week of April, No Labels announced it would not nominate a third-party candidate and ended its 2024 efforts.

A less-organized and less-funded third-party endeavor still could throw sand into the gears this year and alter the course of the race. Once again, Stein is seeking the presidency as a Green Party candidate. (She skipped the 2020 election. Howie Hawkins, a longtime progressive activist and trade unionist, garnered a measly 0.3 percent of the vote for the Greens.) There’s no reason to believe Stein’s appeal has widened since 2016, but the Green Party does have ballot lines in at least 20 states and Washington, DC, including the swing states of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Florida. So she could be a factor in a tight race.

As could Cornel West. The celebrity academic (formerly of Harvard and Princeton), fiery anti-racism campaigner, and onetime leader of Democratic Socialists of America has mounted a long-shot bid as an independent. In January, he announced he also was forming the Justice for All Party to help him gain ballot access in several states, particularly Florida, Washington, and North Carolina—the last of which could be a key Biden–Trump battleground. (In some states, it’s easier for a party than a nonaffiliated candidate to win a line on the ballot, which partly explains West’s desire to form a party.) As of February, he had only qualified to be on the ballots of Oregon, South Carolina, and Alaska. His success in Alaska illustrates the strange-bedfellows world of third-party politics. His campaign paid $10,000 to Scott Kohlhaas, a state ballot access expert who has run and lost races for the US Senate and the Alaska legislature as a Libertarian Party candidate. Kohlhaas also has spearheaded an effort for Alaska to secede from the United States.

Per usual, the national Libertarian Party plans to have a candidate in the 2024 hunt. The party’s past efforts have been uneven. In 2016, the Libertarian ticket of former New Mexico Gov. Gary Johnson and former Massachusetts Gov. Bill Weld appeared on the ballots in all 50 states, but the party’s nominee in 2020 is now a trivia question for politicos (A: Jo Jorgensen). At the end of May, upward of 1,000 delegates will gather for a convention to choose to choose the party’s candidate. Kennedy has held talks with Libertarians about possibly heading their ticket, though there were wide ideological differences between his crazy-quilt collection of policy stances and the Libertarians’ anti-government positions.

It is Kennedy who may well be the true X factor in 2024, even if it’s unclear which candidate his presence could hurt more. When Donald Trump Jr. slammed Kennedy as a “radical liberal,” it suggested that the Trump camp feared his impact on the contest.

The Democratic National Committee is also worried. In February, it filed a complaint with the Federal Election Commission charging that a super-PAC supporting Kennedy (which has received millions of dollars from a Trump funder) and his campaign had illegally coordinated their work—an allegation Kennedy’s campaign denied. The DNC also hired a veteran political operative to lead its opposition to third-party presidential bids, with Kennedy as a top concern.

Third-party and independent candidates always talk about the legitimate need to enlarge the political debate. But they also present the major parties, billionaires, and even foreign governments with opportunities for political mischief.

In 2000, a Republican group aired ads featuring Nader attacking Gore. Four years later, when Nader ran again and drew less support, conservative outfits helped him win ballot access, and Republican funders donated directly to his campaign. This was before Citizens United v. FEC, the 2010 Supreme Court decision that allowed unlimited amounts of anonymous money from billionaires, corporations, and unions to pour into the political system. The profusion of dark money makes it easier for political connivers—domestic and foreign—to secretly influence elections, including by using third-party or independent candidates for their own ends.

These days, there are many ways to exploit such a candidate. Here’s a possible scenario: West makes it onto the ballot in North Carolina. Then, in the closing days of the campaign, a Republican donor—or several donors—sets up a private corporation, which doesn’t have to reveal its owners. This entity pours a large amount of cash into a newly created super-PAC. This super-PAC then uses those funds to air ads on radio stations in, say, Charlotte, Raleigh, Greensboro, and Durham that slam Biden for not doing enough for Black voters and urge a vote for West. Could that cause several thousand voters to defect from Biden to West? Could a difference of several thousand votes decide the election in that state? Could the results in North Carolina swing the entire election? Sneaky moves like this could be attempted in any swing state.

Nor should we forget the history of Russian interference in our elections. In 2016, Russian trolls ran a social media blitz to boost Stein, as part of Moscow’s clandestine scheme to undermine the US presidential election and help Trump. This operation included the hack-and-leak operation that targeted Clinton, via the release of emails and documents stolen from the Democrats, and, no doubt, contributed to her loss. In 2020, Russian operatives colluded with Rudy Giuliani, Trump’s personal lawyer, to spread false information about Joe Biden and his son Hunter’s activities in Ukraine.

This year, Moscow will undoubtedly try to intervene in the American election. Third-party and independent candidates—who, of course, have the right to run and be considered on their merits—offer the Russians and other bad-faith actors avenues for meddling. These schemers can exploit attempts to expand democracy in order to undercut it.

Americans drawn to a third-party or independent candidate might have all sorts of worthy reasons for doing so. Some may see their vote as a blow against the duopoly, while others view it as a means to embrace a purer ideological agenda. Voting for an outsider candidate could be perceived as a way to express a particular frustration with a major-party candidate—say, with Biden’s approach to the Israel–Hamas war. A lifelong Republican who is fed up with a corrupt would-be autocrat who encouraged an insurrection might want an alternative that does not entail marking the ballot for a Democrat. Yet, given the hard-and-fast realities of America’s political system—and the ability of political operatives, big-money donors, and foreign governments to utilize these candidacies for their own purposes—a vote for one of these candidates could lead to results on Election Day and beyond that run counter to third-party voters’ aims for the nation.

It is inconceivable that a candidate who’s not a Democrat or a Republican could win the 2024 presidential contest. But it is not inconceivable that one or more of these outsider candidates could change the course of the election and determine the victor—in other words, be a spoiler. This will likely be a contest that hinges on a small number of swing voters in a handful of states. With the scales evenly balanced, it might not take much to tip them. And if the main choice is indeed between a candidate who threatens democracy and one who abides by its rules and norms, these other presidential wannabes—and their voters—may play a crucial role in deciding the fate of the United States.