The Wall Street Journal, once again, is hellbent on claiming that young people can no longer afford to buy homes:

Homeownership rates for younger Americans have fallen sharply over the last decade….People who came of age in the crisis and its immediate aftermath had no bargaining power when they entered the job market, crimping their earnings ever since. They started adulthood when the housing market was crashing and watched as banks foreclosed on their parents—and decided they weren’t interested in tying their fortunes to a piece of property. Now, as memories of the crisis fade, they want to buy homes but are finding themselves priced out of the market.

….Homeownership rates for young people are near their lowest levels in more than three decades of record-keeping. About 40% of young adults, ages 25 to 34, were homeowners in 2018, according to federal data analyzed by Freddie Mac. That is down from about 48% in 2001, when Gen X-ers were young adults.

This is ridiculous. Of course homeownership rates have fallen sharply since the peak of the housing bubble. Homeownership rates for everyone have fallen since the peak. And homeownership rates had already started getting bubbly in 2001, so it’s hardly a surprise that homeownership rates are also down compared to then.

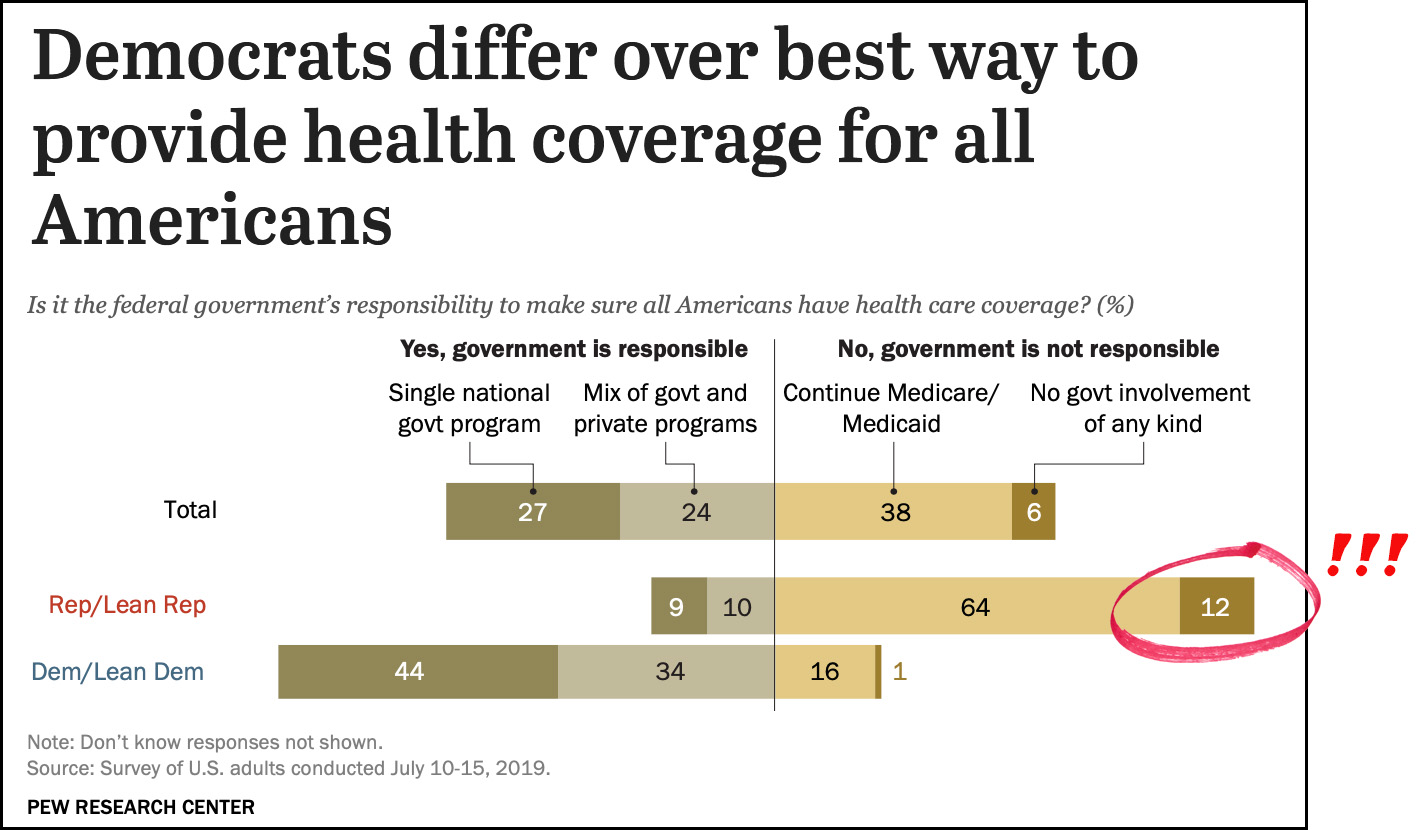

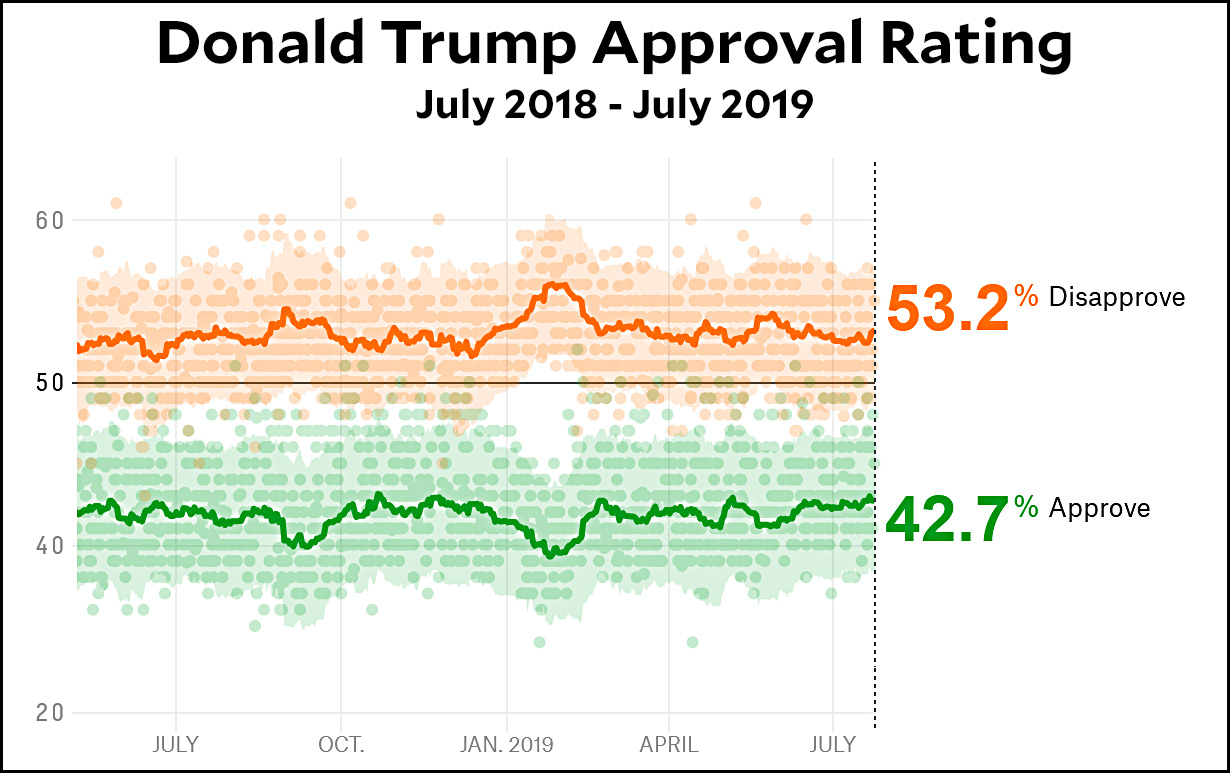

But why cherry pick a few specific years? Here’s the homeownership rate since 1964:

I want to make clear what I’ve done here. The Census Bureau provides homeownership rates for young families starting in 1994. That’s the heavy red line. As you can see, it goes up and down at about the same rate as overall homeownership. In fact, the homeownership rate for those under 35 is roughly 58 percent of the overall rate. Using that number, I extended the line for those under 35 back to 1964. This is the dashed red line. It’s not precise, but I doubt that it’s off by more than a percentage point or two in any given year.

The dotted gray line shows what happened. In short, homeownership rates for those under 35 have always been around 36 percent. The exceptions are 1995-2011, during the bubble, and 2012-18, during the bust. As of 2019, however, homeownership among young families is almost precisely at its historical average. In the second quarter of 2019 it clocked in at 36.4 percent.

This is one of the many myths of our time that I’m sick to death of: the myth that young families can no longer buy homes. Add to this the myth of the retirement crisis. The myth that crime is down because of CompStat (or poverty or abortion or some other plainly ridiculous reason). The myth that illegal immigration is skyrocketing. The myth that American kids are getting dumber. The myth that American health care is the best in the world. The myth that millennials are lazy and self-absorbed.

These aren’t politically-driven distortions, they’re myths that get passed along by folks on all sides without any real thought. They just are. Everyone knows it, so what’s the point of actually looking at the evidence?