Am I the only one this morning who senses that conservatives are pretty disappointed that Iran released our sailors quickly and without any fuss? Maybe I’m just being hypersensitive….

Am I the only one this morning who senses that conservatives are pretty disappointed that Iran released our sailors quickly and without any fuss? Maybe I’m just being hypersensitive….

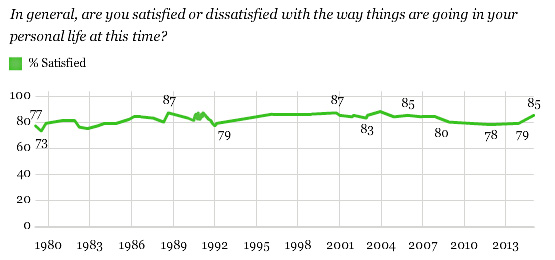

In a Gallup poll released last week, 85 percent of Americans said they were satisfied with how things were going in their personal life. That’s close to an all-time high:

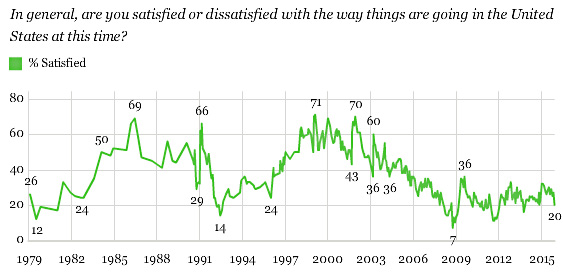

At the same time, only 20 percent are satisfied with how things are going in the United States. That’s not an all-time low, but it’s in the ballpark:

By historical standards, a 6-point increase in personal satisfaction over the course of a single year is pretty huge. If you look at the past three decades, it represents two-thirds of the range from all-time low to all-time high.

But that hasn’t translated into any change in satisfaction with how things are going for the country. A corresponding increase would be something like 40 percentage points. In reality, satisfaction went down in 2015 by about ten points.

There is a story to be written about this massive disconnect. Normally, satisfaction with the country goes up as we recover from recessions. And we have recovered. Employment is up. Inflation is low. Gas prices have dropped. Taxes haven’t changed for anyone even close to middle class. Broadly speaking, things are going pretty well.

The usual response at this point is to say that despite all this, wages are stagnant. And that’s true. But wages have been pretty stagnant for a long time. What’s more, over the past year we’ve actually started to see them rise a bit. Not a lot, but some.

So what’s the deal? Satisfaction with the country started to show normal signs of increase in 2009, but then it suddenly collapsed—and it’s stayed low ever since. Why? Has satisfaction with the country become unmoored from economic conditions? Is it all about other hot buttons these days? Are conservatives unhappy because gays are getting married while liberals are unhappy because income inequality is increasing? Have we all somehow conspired to be massively dissatisfied with the state of the country because our side continues to fail to get everything we want? Or what?

We don’t live in nirvana. We never have. But by most standards, things are going pretty well. For liberals, we have gay marriage, Obamacare, and better Wall Street regulation. For conservatives, we have Citizens United, continued low taxes, and total control of Congress. For everyone, crime is down, school test scores are up, and terrorists continue to kill virtually no one here in America.

I honestly don’t get it. America isn’t a utopia, and America isn’t a dystopia. It’s recovering pretty decently from a huge recession and personal satisfaction with life is high. On other fronts, lots of things are going well and a few aren’t. Same as always.

So why all the anger? Can it really be laid at the feet of the media? What’s going on?

In an apparent effort to prove that you can do data journalism on literally any topic, Leah Libresco examines the merchandising bonanza of the latest Star Wars movie:

The most-recent “Star Wars” Monopoly set did what the villain of “Star Wars: The Force Awakens” couldn’t, sidelining Rey, the film’s female protagonist…. Fans signed petitions, wrote letters, and tweeted their outrage using

the “#WheresRey” hashtag…. The controversy reached its climax when Hasbro, the maker of the game, said Rey will be represented in new editions.

To see whether Rey’s absence was local to Monopoly or more widespread across all “Force Awakens” toys, I did what any sensible data journalist would do: I went to a toy store. Well, a digital one. Toys R Us lists 256 toys in their online “Force Awakens” store, but only 70 of them include any of the major characters introduced in the new movie. Rey holds her own among this group.

“Rey holds her own”? I guess so. She and Finn are the main heroes of the movie, and they’re pretty close in the toy competition. The real news here is a clear anti-human bias: the biggest toy winners are Kylo and Captain Phasma, who spend most or all of the movie in masks, and BB-8, a droid so calculatingly adorable as to bring back involuntary memories of Ewoks.

Anyway, as long as we’re on the subject, you’ve probably all been waiting on the edges of your seats wondering what I thought of the movie. Well, the first week it was too crowded, so I didn’t go. I’m too old for standing in line. The next week, the kids were still out of school, and a friend was visiting who had no interest in the movie. The next week, my mother’s car broke, so I loaned her mine and had no way to get to the theater. By the time I got my car back, I had come down with a cold and didn’t feel like going. So it wasn’t until yesterday that I finally I saw it.

And I was stunned. I was prepared for anything from bad to pretty good, but it turned out to be stultifyingly boring. There’s nothing “wrong” with SWTFA. The acting is OK. The dialog is OK. The effects are OK. The pacing is OK. The direction is OK. The editing is OK. The characters are OK. As a piece of craft, it’s fine. But when you put it all together it’s two hours of nothing. And yet, the residents of Earth have spent a billion dollars on tickets! What the hell is wrong with you people?

The movie’s big mystery, of course, is “Who is Rey?” The answer is, “Who cares?” Here’s my guess: she’s a clone constructed from a preserved pubic hair of Obi-Wan Kenobi. We’ll find out in the exciting sequel!

Anyway, JJ Abrams has now ruined Lost. He’s ruined Star Trek. And he’s ruined Star Wars. He’s a one-man wrecking crew. But there’s a silver lining: at least I can now say with confidence that I’ll never waste money seeing a JJ Abrams production again.

And now for the worst part. I never thought it was possible I’d say this, but I have marginally more respect for George Lucas’s prequels now. They may have sucked, but at least he tried.

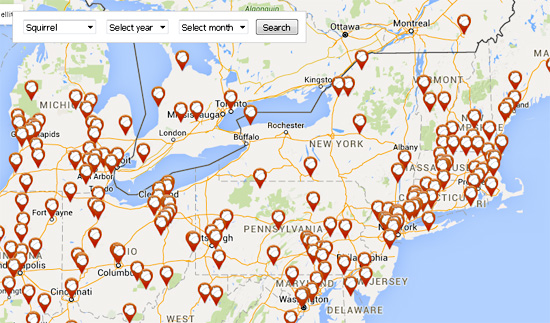

The American electrical grid remained under sustained assault in 2015 from squirrel attacks. The Obama administration, feckless as always, failed to understand the threat and protect the American people. If they refuse to even say the words “evolutionarily maladapted squirrels,” what chance do they have of defeating the enemy?

Wagers that the yuan will slump 10% or more against the dollar are “ridiculous and impossible,” a senior Chinese economic official said Monday, warning that China had a sufficient tool kit to defeat attacks on its currency. “Attempts to sell short the renminbi will not succeed,” said Han Jun, deputy director of the office of the Central Leading Group on Financial and Economic Affairs, at a briefing at the Chinese Consulate in New York.

I suppose he’s probably right. Still, this has an uncomfortable ring of the kind of thing treasury officials tend to say just before a sustained assault on their currency demonstrates that even huge autocracies with lots of foreign reserves aren’t immune to market forces. Stay tuned.

Here is Donald Trump in a 1990 Playboy interview:

Here is Donald Trump in a 1990 Playboy interview:

What does all this—the yacht, the bronze tower, the casinos—really mean to you?

Props for the show.And what is the show?

The show is “Trump” and it has sold out performances everywhere. I’ve had fun doing it and will continue to have fun, and I think most people enjoy it.….What were your [] impressions of the Soviet Union?

I was very unimpressed….Russia is out of control and the leadership knows it. That’s my problem with Gorbachev. Not a firm enough hand.You mean firm hand as in China?

When the students poured into Tiananmen Square, the Chinese government almost blew it. Then they were vicious, they were horrible, but they put it down with strength. That shows you the power of strength. Our country is right now perceived as weak … as being spit on by the rest of the world—

So after eight years of Ronald Reagan, within weeks of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Trump is convinced that America is perceived as weak. I guess in Trumpland, America is always weak. Too bad we’re not more like the Chinese at Tiananmen Square. Sure, they almost blew it, but in the end they did what they had to do. I guess they would have known what to do with those Occupy hippies and all the Mexicans flooding into the country too.

My piece on assisted suicide went up today, and just in case there are any readers who think I wrote it as a subtle way of saying that things are going badly with my multiple myeloma, I didn’t. This is something that’s been on my radar for a while, and it was Jerry Brown signing California’s right-to-die bill last year that prompted me to finally write about it.

In fact, my health is pretty amazingly good right now. Even my back has nearly returned to normal—close enough that I’ve started up disc golfing again on weekends. Aside from the normal twinges and squeaks of a 57-year-old body, there’s nothing wrong with me. The myeloma is basically like having high cholesterol: you know there’s some stuff going on inside that’s bad and will eventually cause trouble, but in the meantime it isn’t causing any problems at all.

As for my longer term diagnosis, I don’t know yet. After my last visit with my oncologist I finally requested a new one. I had put this off for a long time just due to laziness, but I finally had enough with her. My first visit with the new doc is tomorrow, and we’ll see how that goes—though I doubt I’ll have any real news for months. In the meantime, I’m buoyed by the rather startling outbreak of new treatments for multiple myeloma that have suddenly come to market. It’s not that they’re a lot better than the current ones, but different people react in surprisingly disparate ways to different treatments. So there’s at least a decent chance that eventually one of these new treatments might turn out to more effective on me than the ones I’ve had so far. We’ll see.

Cells are amazing—and amazingly complex—little micro-factories. So complex, in fact, that it took longer for eukaryotic cells to evolve—a billion years, at least—than it did for the first multicellular creature to evolve into you and me—around 700 million years.

So how did single-celled critters first join together, anyway? The Washington Post reports today on a new discovery that might explain the ancient origin of multicellular organisms that eventually became Homo sapiens. It comes from a team of researchers at  the University of Oregon. One of the co-authors is Ken Prehoda, a biochemist:

the University of Oregon. One of the co-authors is Ken Prehoda, a biochemist:

The discovery was made thanks to choanoflagellates — tiny balloon-shaped creatures that are our closest living unicellular cousins….They’re single-celled organisms, but they occasionally work together in groups, swimming into a cluster with their flagella (tails) pointing outward like the rays of a sun. At the most basic level, this coordination helps the choanoflagellates eat certain kinds of food. But it’s also an example of individual cells coming together to work as one unit, kind of like — hey! — a multi-cellular organism.

Prehoda and his colleagues began to look into what genes could be responsible for allowing the choanoflagellates to work together. “We were expecting many genes to be involved, working together in certain ways, because [the jump to multi-cellularity] seems like a really difficult thing to do,” he said.

But it turned out that only one was needed: A single mutation that repurposed a certain type of protein [so that it] could communicate with and bind to other proteins, a useful skill for cells that have decided to trade the rugged individualist life for the collaboration of a group….Every example of cells collaborating that has arisen since — from the trilobites of 500 million years ago to the dinosaurs, woolly mammoths and you — probably relied on it or some other similar mutation.

One little mutation, and single cells in a swarm could communicate slightly better than before. This presumably allowed better coordination, and thus more access to food and a better chance of survival. Or, if you prefer your science a little less comprehensible: “A molecular complex scaffolded by the GK protein-interaction domain (GKPID) mediates spindle orientation in diverse animal taxa by linking microtubule motor proteins to a marker protein on the cell cortex localized by external cues….The evolution of GKPID’s capacity to bind the cortical marker protein can be recapitulated by reintroducing a single historical substitution into the reconstructed ancestral GKPID.”

Thanks, GKPID! You don’t get all the credit (or blame) for the evolution of us humans, but without your willingness to try new things and share your feelings with your fellow proteins, we probably wouldn’t be around today.

The argument for a union shop is pretty straightforward: even if you hate your union, they perform collective bargaining for everyone, including you. Since you benefit from that bargaining, you should be required to pay union dues. After all, if dues are optional, why would anyone pay? Why not just let all the other suckers pay while you reap the benefits free of charge?

There’s another version of this argument that’s even more straightforward: if union shops are illegal—as they are in so-called “right to work” states—it’s all but impossible to set up a union. This is why the Chamber of Commerce and pretty much all Republicans are great fans of the open shop. It basically destroys the ability of unions to operate.

But what about public employee unions? What if you object to your union’s political views and don’t want to sponsor them? The answer, in many states, is that you can partially opt out of union dues, paying only an “agency fee” specifically designated for collective bargaining activities.

Problem solved? Not quite. What if you think that even collective bargaining is inherently a political stance when you’re bargaining with the government? Should you be allowed to opt out of union dues entirely? Today the Supreme Court heard arguments on this, and it didn’t go well for union supporters:

The justices appeared divided along familiar lines during an extended argument over whether government workers who choose not to join unions may nonetheless be required to help pay for collective bargaining. The court’s conservative majority appeared ready to say that such compelled financial support violates the First Amendment.

Collective bargaining, Justice Anthony M. Kennedy said, is inherently political when the government is the employer, and issues like merit pay, promotions and classroom size are subject to negotiation.

The best hope for a victory for the unions had rested with Justice Antonin Scalia, who has written and said things sympathetic to their position. But he was consistently hostileon Monday. “The problem is that everything

that is bargained for with the government is within the political sphere,” he said.

In one sense, there’s nothing new to say about this. The liberal-conservative split on the Supreme Court has hardened over the past couple of decades, and we simply don’t see very much principled opposition to party lines anymore. Conservatives hate unions, so conservative Supreme Court justices are going to rule against unions whenever and wherever possible. They’ll make up the reasons afterward.

But there’s another sense in which this is interesting: it’s yet another step in the evolution of the conservative Supreme Court’s insistence that money is speech. In Citizens United and subsequent cases, they’ve all but wiped out any possible regulation of campaign finance on the grounds that campaign donations fund campaign speech. So if you can’t regulate political speech, you can’t regulate political money either.

Now they seem set to do the same for unions. If collective bargaining is inherently political speech, then you can’t force people to fund it. That’s a prima facie violation of the First Amendment.

I wonder how far this can go? After all, you can make a case that spending money is nearly always implicit speech: my purchase of a Snickers bar is a public declaration that Snickers bars are delicious, and my company’s dodgy advertising claims are a declaration of deeply held corporate emotions. So much for regulation of sugary snacks or false advertising.

Money is speech. Speech can’t be regulated. Therefore, money can’t be regulated. It’s a pretty simple syllogism. And, possibly, a pretty handy one.

I’m not as cynical about the purpose of universal education as the late Aaron Swartz, but I love this historical retrospective from a piece of his reprinted today in the New Republic:

I’m not as cynical about the purpose of universal education as the late Aaron Swartz, but I love this historical retrospective from a piece of his reprinted today in the New Republic:

In 1845, only 45 percent of Boston’s brightest students knew that water expands when it freezes….In 1898, a…Harvard report found only 4 percent of applicants “could write an essay, spell, or properly punctuate a sentence.” But that didn’t stop editorialists from complaining about how things were better in the old days. Back when they went to school, complained the editors of the New York Sun in 1902, children “had to do a little work. … Spelling, writing and arithmetic were not electives, and you had to learn.”

In 1913…more than half of new recruits to the Army during World War I “were not able to write a simple letter or read a newspaper with ease.” In 1927, the National Association of Manufacturers complained that 40 percent of high school graduates could not perform simple arithmetic or accurately express themselves in English.

….A 1943 test by the New York Times found that only 29 percent of college freshmen knew that St. Louis was on the Mississippi….A 1951 test in LA found that more than half of eighth graders couldn’t calculate 8 percent sales tax on an $8 purchase….In 1958, U.S. News and World Report lamented that “fifty years ago a high-school diploma meant something…. We have simply misled our students and misled the nation by handing out high-school diplomas to those who we well know had none of the intellectual qualifications that a high-school diploma is supposed to represent—and does represent in other countries. It is this dilution of standards which has put us in our present serious plight.”

A 1962 Gallup poll found “just 21 percent looked at books even casually.” In 1974, Reader’s Digest asked, “Are we becoming a nation of illiterates? [There is an] evident sag in both writing and reading…at a time when the complexity of our institutions calls for ever-higher literacy just to function effectively.”

Education was always better in the old days. Except that it wasn’t. As near as I can tell, virtually all the evidence—both anecdotal and systematic—suggests that every generation of children has left high school knowing as much or more than the previous generation. Maybe I’m wrong about that. But if I am, I sure haven’t seen anyone deliver the proof.