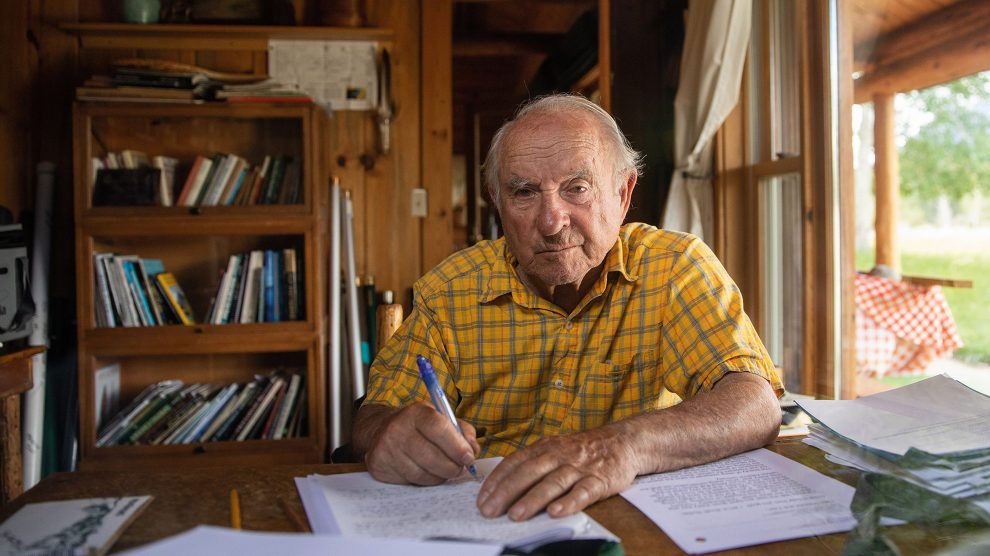

Courtesy Patagonia via ZUMA Press Wire

This story was originally published by the Guardian and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

The publication of a magazine article in 2017 “really, really pissed off” Yvon Chouinard, the mountain climber turned reluctant businessman and founder of outdoor clothing company Patagonia.

In the article, Forbes crowned Chouinard as a billionaire and added him to its list of the world’s richest people. While many people daydream of achieving a nine-zero fortune, for Chouinard it was a sign he had failed in his life’s mission to make the world a better and fairer place.

The Forbes article set him on a journey to find a way of giving away Patagonia, the company he founded almost 50 years ago with a mission to help fellow climbers. This week he achieved that aim, announcing that he was giving away all of the shares in Patagonia to a trust that will use future profits to “help fight” the climate crisis.

“Earth is now our only shareholder,” Chouinard, 83, said in a message to staff and customers. “Instead of ‘going public’, you could say we’re ‘going purpose’. Instead of extracting value from nature and transforming it into wealth for investors, we’ll use the wealth Patagonia creates to protect the source of all wealth.”

Explaining his decision to give away the company, Chouinard told the New York Times: “I was in Forbes magazine listed as a billionaire, which really, really pissed me off. I don’t have $1 billion in the bank. I don’t drive Lexuses.”

Chouinard, who drives a beaten-up Subaru with a surfboard strapped to the roof, says he hopes giving away the company “will influence a new form of capitalism that doesn’t end up with a few rich people and a bunch of poor people”.

He is a businessperson, but very much by accident, and finds the descriptor offensive. He once told a journalist from Outside Magazine during a multi-day climbing trip up Mount Arrowhead, in Wyoming, that he would prefer to be referred to as a “dirtbag”.

Challenged by the reporter, who argued that you can’t be a multimillionaire and a dirtbag, Chouinard said he gave away all of this money and he doesn’t “even have a savings account”.

“But that’s not even the point,” Chouinard continued. “Being a dirtbag is a matter of philosophy, not personal wealth. I’m an existential dirtbag.”

Refusing to let it go, the reporter tried again saying Chouinard was a “very successful businessman” and “somewhere along the way you must have wanted to be a businessman.” Chouinard exploded back: “Never! All I ever wanted to be was a craftsman.”

And that is how he started. In 1957 he bought a second-hand coal-fired forge and set up a blacksmith shop in a chicken coop in his parents’ back yard in Burbank, California. He hand-made pitons—metal pegs or spikes driven into a rocks to support climbers’ ropes.

The pitons proved very popular with his friends and other climbers. It was also profitable as he could forge two pitons an hour and sell them for $1.50 each (the equivalent of about $16 today), giving Chouinard time and money to spend adventuring.

“I’d often climb for half a day at Stoney Point in Chatsworth, then go up to Rincon [to surf] the evening glass, [and] after I’d free-dive for lobsters and abalone on the coast between Zuma and the county line,” he wrote in his memoir Some Stories: Lessons from the Edge of Business and Sport. “I almost always got my limit of 10 lobsters and five abalone.”

Soon he figured out that he could pack up his blacksmith tools and take them with him as he surfed his way up and down the west of the US during the winter, and on climbing trips across the US and Canada in the summer. One year he spent weeks in the Rockies surviving on a case of 5¢ cans of tuna cat food mixed with oatmeal, potatoes, “ground squirrel, blue grouse, and porcupines assassinated à la Trotsky, with an ice axe.”

Some years he spent more than 200 nights sleeping outside, and claims not to have owned a tent until he was almost 40. In 1962 he was arrested for riding a freight train in Arizona and spent 18 days in jail on a charge of “wandering around aimlessly with no apparent means of support”.

The idea of setting up a clothing business came about on a climbing trip. In Scotland in the winter of 1970, he bought a rugby shirt to wear while rock climbing as the thick collar kept his hardware slings, loaded with heavy equipment, from cutting into his neck. He kept wearing the top—which was azure blue with two red and one yellow stripes—when back in the US, and his climbing friends asked where they could get one.

He found out and started importing them, before expanding into other clothing and equipment for climbing. The company was originally called Chouinard Equipment, before he changed it after a transformative trip to Patagonia, in southern South America, to climb Mount Fitz Roy with his best friend, Doug Tompkins, the founder of rival outdoors company the North Face.

In another memoir, Let My People Go Surfing: The Education of a Reluctant Businessman, Chouinard wrote that if he “had to be a businessman” he was “going to do it on my own terms.”

“Work had to be enjoyable on a daily basis. We all had to come to work on the balls of our feet and go up the stairs two steps at a time. We needed to be surrounded by friends who could dress whatever way they wanted, even be barefoot,” he wrote.

Decades before the pandemic, flexible working was always the standard at Patagonia, which is headquartered in Ventura, California, because it is one of the world’s best surfing spots.

“We don’t care when you work, as long as the work gets done,” he said in a speech at the University of California, Los Angeles. “If you’re a serious surfer, you don’t go, ‘Hey let’s go surfing next Thursday at 2pm’—that’s what losers say.”

“You go surfing when there’s surf, you go powder skiing when there’s powder. We wanted to have a job where we would be allowed to do that. And we wanted to go work with friends—we didn’t want to work with MBAs,” he said. “We wanted to break the rules of business.”