In Chrystia Freeland’s Atlantic piece about the new “global elite,” she defined them like this: “Its members are hardworking, highly educated, jet-setting meritocrats who feel they are the deserving winners of a tough, worldwide economic competition—and many of them, as a result, have an ambivalent attitude toward those of us who didn’t succeed so spectacularly.” That reminded me of one of my favorite passages from Matt Bai’s The Argument. This is from Chapter 5, which tells the story of Rob Stein’s attempt, following the 2004 election, to create a group of super-rich liberal donors called the Democracy Alliance:

Although he had now spent the better part of two years bonding with liberal millionaires and acting as their political therapist, Rob was still a peculiarly Washington figure, a mere interloper in the world of hedge funds and Lear jets. And this, in the short term, would be his undoing.

….Steven Gluckstern and his wife, Judy, lived in a 7,500-square-foot open loft on Spring Street in Soho, with a spacious garden on the roof and mgnificent views of the Empire State Building to the North….He made his fortune in the reinsurance industry, working first for the billionaire Warren

Buffet and then with a partner, and had recently retired from the $4 billion investment fund he had helped start. I heard grumbling from some of the other, richer partners that Steven wasn’t really that good at making money, but if that was true, then it was clearly relative. He was certainly better at it than anyone I knew in Washington.

….Like most of the partners I met, Steven applied the mystical language of business to his work with the Alliance….He talked about doing “due diligence” on these groups, about “capitalizing” them, so they could be “brought to scale.” He talked about finding “customers” for the Democratic “product.” It was clear, spending time with Gluckstern and other partners, that they felt they had identified with some precision the cause of these recurrent Democratic failures: the problem was that the party was being run by a bunch of political experts, when, in fact, it needed to be run like a business….The way the partners saw it, people who were really smart made tons of money, and if you didn’t make tons of money, then you couldn’t be very smart.

….From the beginning, Rob Stein had been highly attuned to this worldview….And yet, much as he seemed to speak the language, he could not escape what he represented in the minds of many donors. In Steven’s view, Rob had spent too much of his career in Washington. And, as if to confirm his suspicions, Rob’s most recent job had been to manage a private investment fund—and still Rob hadn’t gotten rich….What did it say about a man when he started a fund and somehow didn’t walk away with millions of dollars? As far as Steven was concerned, that in itself probably disqualified Rob from making the big decisions.

Emphasis mine. Now compare this to a passage from An American Melodrama, written 40 years ago by a trio of London Times reporters about the 1968 election:

There is one very good reason why [] the exploitation of mass media should actually be negatively correlated with radicalism. The new political technology is very expensive. It depends on computers, public opinion surveys, film, videotape, and other expensive toys. It also depends on the services of clever, highly educated and trained people to use these techniques….In general, it is naive to suppose that techniques which can be used only by those with access to enormous financial resources will often be available for any really damaging assault on the status quo.

Emphasis mine again. I will leave the obvious conclusion as an exercise for the reader.

Expedite Nominations: Reduce Post-Cloture Time

Expedite Nominations: Reduce Post-Cloture Time get to see their advantages — low carbon emissions — reflected in their price.

get to see their advantages — low carbon emissions — reflected in their price. is that intense globalization goes a long way toward explaining why the super rich don’t really seem to

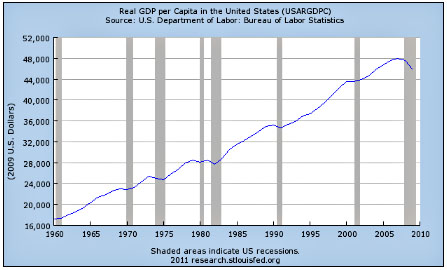

is that intense globalization goes a long way toward explaining why the super rich don’t really seem to  me, whose wages haven’t kept up with economic growth, thus creating a huge and growing pool of extra money for the financiers to hoover up.

me, whose wages haven’t kept up with economic growth, thus creating a huge and growing pool of extra money for the financiers to hoover up. removed from movies that are aired on TV “without taking away from the central themes of the story,” he says,

removed from movies that are aired on TV “without taking away from the central themes of the story,” he says,  interesting confrontation, but it’s also a bit of a sideshow: the prisoners themselves, after all, have no real reason to care whether they’re held forever in Cuba or Michigan. But that’s pretty much what Obama intends to do. Amos Guiora and Laurie Blank

interesting confrontation, but it’s also a bit of a sideshow: the prisoners themselves, after all, have no real reason to care whether they’re held forever in Cuba or Michigan. But that’s pretty much what Obama intends to do. Amos Guiora and Laurie Blank