You probably need something to cheer you up after the tax follies of this week. So how about a scholarly examination of how many Americans were killed by atomic bomb testing in the 50s? I think that should do the trick.

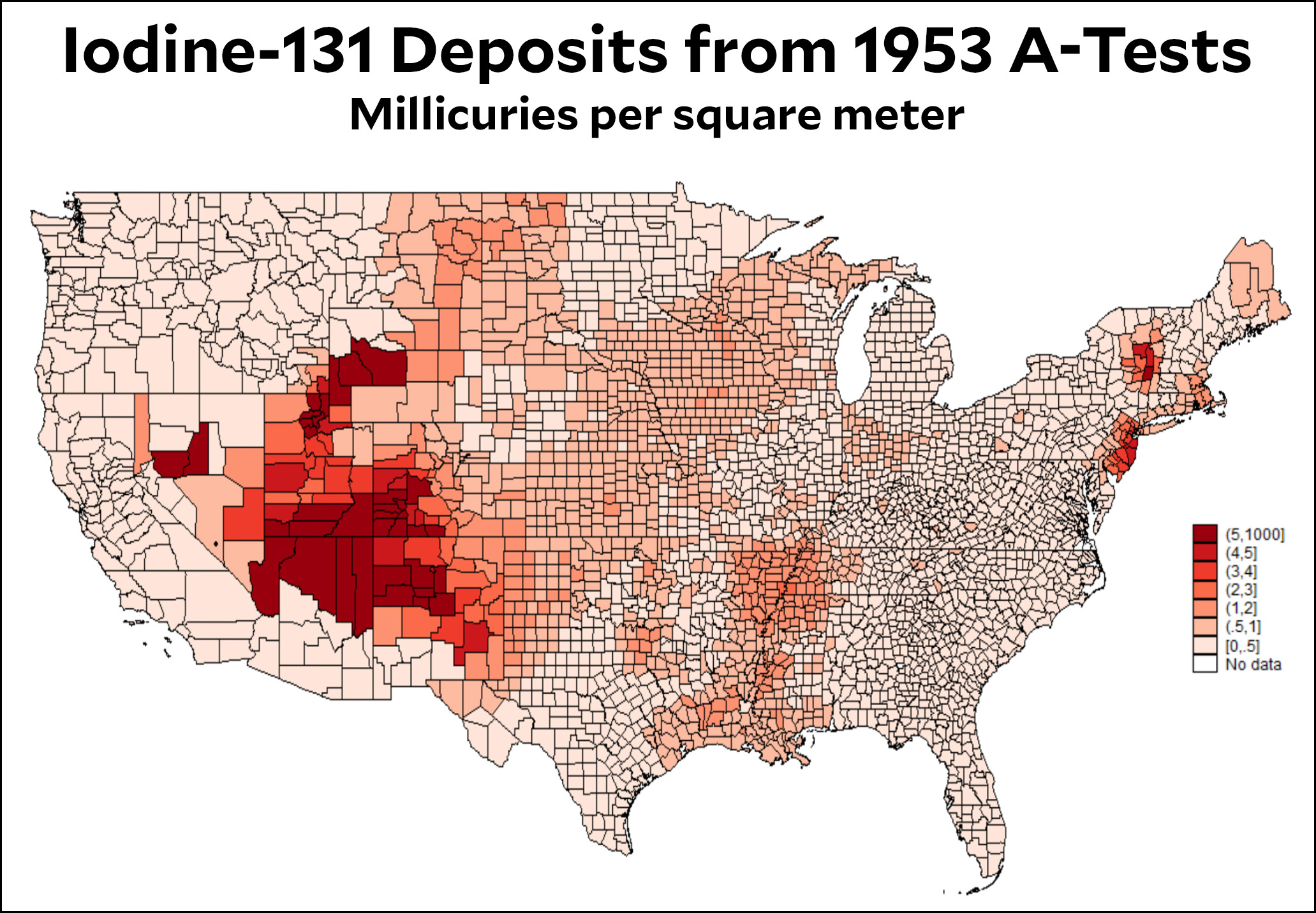

Here’s the background. After 1949, the US moved most of its atomic bomb testing from the South Pacific to a test facility in Nevada. These were all above-ground tests that generated quite a bit of radioactive fallout, including an especially dangerous isotope of Iodine called Iodine-131. The map below shows the deposits of Iodine-131 from a typical series of tests done in 1953:

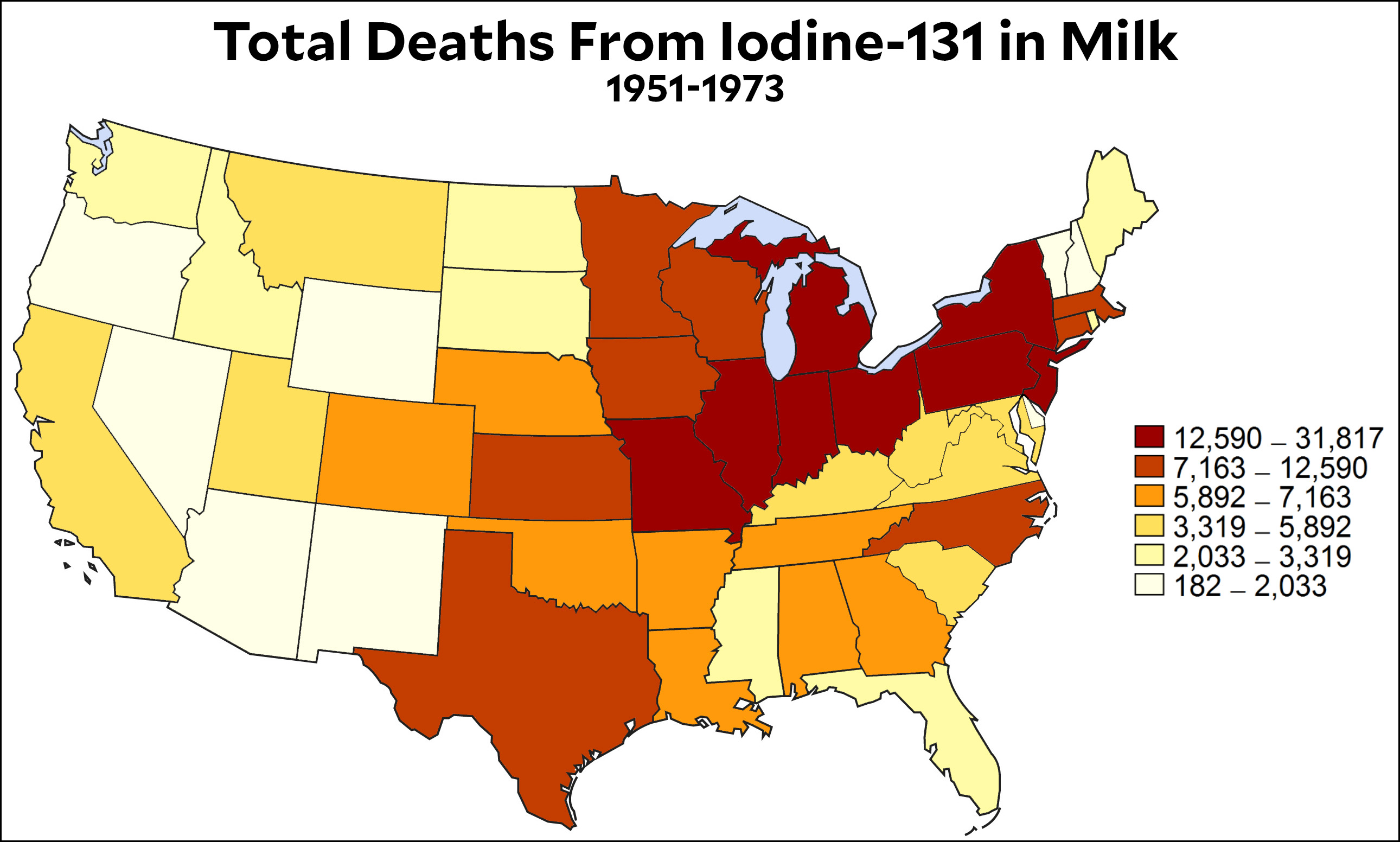

As you’d expect, the highest concentrations are immediately downwind of the Nevada Test Site, with a couple of odd hot zones in New Jersey and upstate New York. Luckily, these are mostly areas of sparse population. Unluckily, this doesn’t matter much because it’s not the primary way that Iodine-131 kills people. Most of it ends up being carried by high-altitude winds and then deposited by rainfalls throughout the country. From there it gets into pastureland and then into the milk supply, where it attacks the thyroid. In a new working paper (i.e., still a bit preliminary) Keith Meyers made use of extensive datasets on milk consumption and local death rates and produced a map that shows which areas were most heavily affected:

It turns out that the victims were mostly quite far away from Nevada. A combination of extensive dairy farming and high populations meant that most fatalities were in the upper Midwest extending all the way over to the Eastern seaboard. A rough calculation suggests that the total death toll from testing during the 50s clocked in at about 400,000, far higher than most previous estimates. Children were disproportionately affected because they drink more milk and have smaller thyroids.

But there is, surprisingly, some good news here too. Starting in 1958, and then made permanent by the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty, atmospheric testing was halted. Meyers figures that the testing which was moved underground between 1958-1992 probably saved millions of lives. So it could have been a lot worse.

UPDATE: The original post said that underground testing saved 12-24 million lives, which is indeed the rough estimate in the paper. However, that comes with a number of caveats, and the actual number is most likely smaller. I’ve changed the text to reflect this.