Pharoahe Monch and Th1rt3en; Marcus Machado and Daru Jones

On the morning after media outlets reported that Joe Biden had won the 2020 election, Pharoahe Monch tweeted a parting message to the dearly departing 45th president: “SIMON SAYS! GTF(OUT)!” The hip-hop luminary shared a video of voters dancing in the streets of New York City to a verse made immortal by Monch, with everyone chanting, “Simon says, Get the fuck up! Throw your hands in the sky.”

“It’s an honor to be a part of the global soundtrack” of celebration and repudiation, Monch said, telling me days later about the thrill of hearing his signature sounds lit up by voters affirming “their choice in a democracy with this record.”

His latest single, “Fight,” expands his range as emcee and filmmaker in a fiery collaboration with Cypress Hill. It’s an explosive song set to a short film of a Molotov cocktail hurling in slow motion. The lyrics and visuals are all flames—action, horror, vengeance, Klan robes set ablaze. But what makes “Fight” so intricate, and Monch so subtle a storyteller, isn’t the imagery alone; it’s the scrambling of storyline, themes, and characters. Just as the Molotov is thrown in what looks like the direction of a cop’s house, with his family inside, there’s a hard pivot. The plot changes. Targets and concepts move. The near-flattening of action into a binary—heroes and monsters, saints and sinners—takes a detour. “Fight” becomes a call to action, but it’s a call to get the targets right.

The originality of “Fight” is in its use of an external fight to wage an internal one, an unpacking of what justice can look and sound like. “We were shooting this scene of a young lady lighting a Molotov,” he tells me. “It’s shot really slow. She throws it a couple times. She’s apprehensive, tired. She’s lighting it, lighting it.”

“Cut!” Monch approaches her. “When you throw this bottle, throw that shit! Throw it with who you are.”

After another take, “she started to tear up. She broke down. There’s a young kid on the set looking at me, and she’s crying too. The assistant director was like, ‘Do you know what we just got here?’ Then I started crying. It was powerful.”

The production coordinator, Zoi Ellis, tells me about the pin-drop silence, the emotional and historical weight of the moment: “It was the most incredible production I’ve ever been a part of…There weren’t many dry eyes on the set.”

“That’s what we were dealing with,” Monch says. “They’re like, ‘Yo, Pharoahe’s crying too.’ That was just another fucking dope thing. We were all in tears. I still feel this energy, the vibrations and rhythm that feel like a pendulum swinging back and forth. America is so divided right now.” Asked how to build a movement of unity through music, he points away from the trappings and tripwires of social media: “So much nuance is lost there, but music can bring that conversation with nuance. It feels like we’re designed to be divided purposefully.”

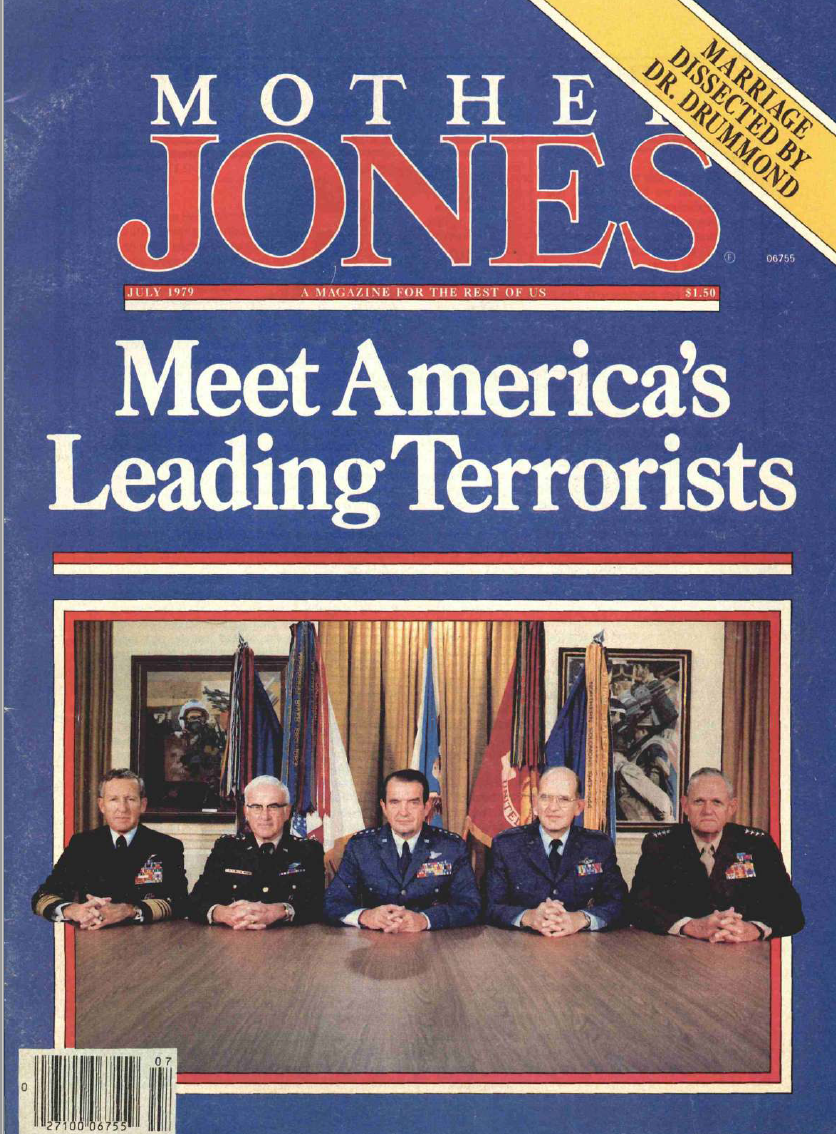

“This Trump guy, knowing who he is and how he riled up his base, I have a more spiritual and global humanity and want to think collectively, like how do you exorcise the darkness that has transpired?”

Our conversation veers from rap to film to jazz in a three-way call with another filmmaker, Nat Livingston Johnson of the directorial duo Peking. I invited Johnson into the call to hear two of today’s talented filmmakers trade notes about their storytelling styles: similarly raw emotional depth, intricate detail, tense pacing, cinematically tight story arcs. Answering a question from Johnson about how to reconcile rap’s roots of justice with a few hip-hop stars’ endorsements of Trump, Monch doesn’t single anyone out. Instead he critiques the warping effects of fame and fortune: “We’re all jaded with the pretentiousness of hip-hop and art in general right now. When you look at art, you have to ask yourself, ‘Are you trying to fool me? Are you trying to get me to buy something? Are you trying to get me to click somewhere? What is this?’”

“If you’re this huge star and live in the hills and have a mansion, I don’t understand what I’m even looking at,” Monch says. “I don’t understand why I’m supposed to be invested in that. I’m like, yo, let’s go heavy art instead and campaign with it and move to the person who appreciates that type of musicianship that evokes that I’m serious about this shit.”

Monch has built the loyalty and trust of diehard fans by opening up about his struggles and growth. “But it took me time to be like, yo, I’m not lying. I’m sending this shit to all my friends. I discovered some shit and I want to share it with someone. I want that feeling.”

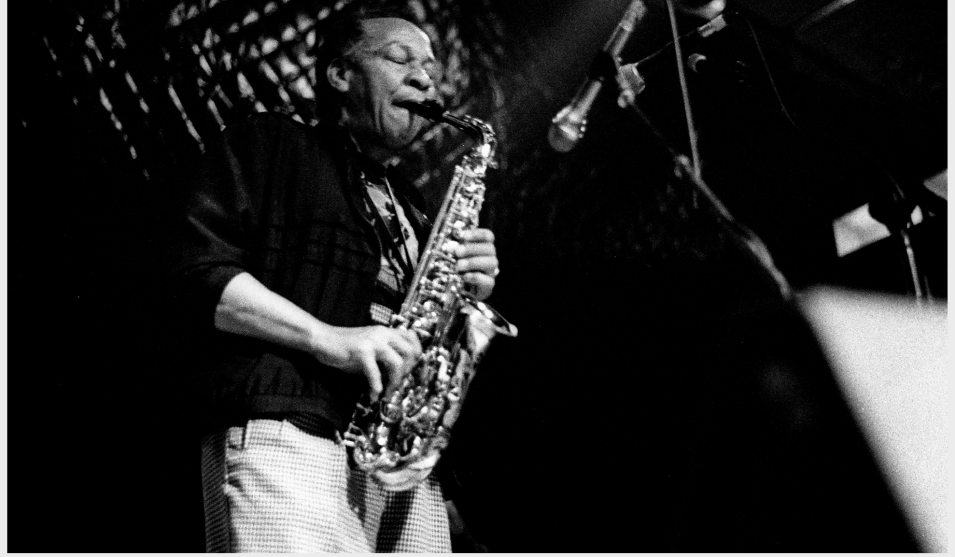

“Fight” is both hip-hop power and rock-star eruption, fueled by the guitar of Marcus Machado and the drums of Daru Jones. Beyond rap and film, Monch has recorded with jazz musicians Robert Glasper and Marcus Strickland and absorbed elements of John Coltrane’s tenor. “Coltrane was one of my main influences when I was developing my voice. His bending the note, breath control, his sheer expression of emotion.”

Breath control means survival for Monch, who’s lived with asthma since childhood, a condition he raps about in “Still Standing”:

13 months old with a lung disease

That almost took my life twice,

Brought me to my knees,

A system not designed for you to achieve.

If “Still Standing” is a story of breathing to survive, “Fight” is about surviving to breathe, persevering under the threat of cop corruption away from cameras:

This little piggy killed a minor.

Same piggy got paid to stay home.

This next pork chop removed his bodycam

And he aimed his Glock at my dome.

Monch moves “beyond the pen and paper,” he tells me. “It’s how you express yourself in the literature and tones.” He welcomes “coming to your own conclusions” about whether “Fight” resolves or reinforces the tension it shows. “I like that about art generally. At its best, you’re standing in a museum looking at a painting for 15 or 20 minutes and think about what it means to you, and someone can look over your shoulder and see something completely different.”

Th1rt3en’s debut record, A Magnificent Day for an Exorcism, is scheduled to be released on January 22, 2021.