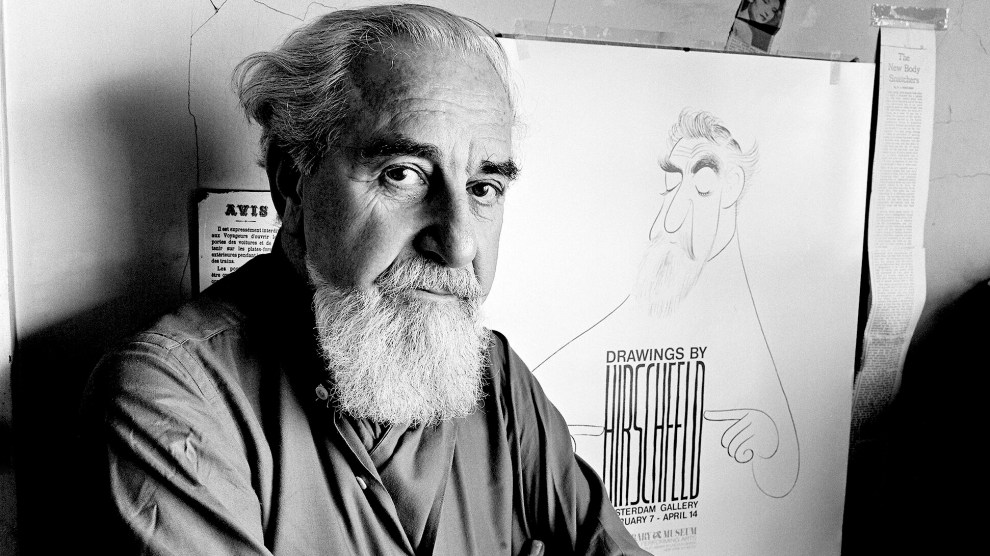

The artist widely smiling in 1974Michael Tighe/Donaldson Collection/Getty

It’s the national pastime that became a national insanity, an obsession shared by millions of people poring over Al Hirschfeld’s caricatures on a scavenger hunt: the Nina challenge. Could you spot the letters of his daughter’s name camouflaged in those lyrically sweeping line drawings?

Hirschfeld was the most prized and prolific caricaturist of magazines, newspapers, and theater bills in the 20th century. He created some 10,000 drawings. If you squint at many, you’ll find NINA tucked in those tangles of hair, cheeks, grins, and growls of politicians and entertainers. The game was all in good fun, a bit of fan service, but more was going on between the lines.

The artist’s stamp—hiding a name—was dear to his fatherly heart. It was also a proxy for a larger project, prompting us to look closely and notice the unnoticed, to see big pictures in small details. That’s one of the many insights in the new biography by Ellen Stern, handpicked by Hirschfeld to write it (and an author I’ve long known as a friend’s family member). Her book is a trove of journalistic interviews with 325 people and a deep dive into archives with surprising dispatches and hidden histories.

It’s a fun read. Formerly of New York and GQ magazines, Stern writes with the same wit that Hirschfeld drew with. Both the author and the artist are vivid storytellers; neither strikes me as pursuing the lofty academic exercise of pondering the pen’s purpose—too heavy for Hirschfeld—but each opens up a new way to understand how caricature reveals essence.

And there is a saving asymmetry between her style and his. Where Hirschfeld embellished the people he drew, Stern refuses to embellish him. She is unsparingly journalistic, a tireless fact-checker. Take the day in March 1965 when Hirschfeld visits the White House: President Johnson at his desk, Hirschfeld the guest of honor. The White House phone rings. Martin Luther King Jr. is on the line. His voice booms into the Oval Office by speakerphone from Selma, Alabama, where King leads a march into a hornet’s nest of white supremacy. Hirschfeld bears witness to history.

Or so he’s fond of telling.

Stern’s research casts damning doubt on whether the call happened that day, and whether Hirschfeld is a reliable narrator of events. The presidential daily diary “does not, in fact, show a phone call to or from Martin Luther King on March 9,” she finds, “nor do the White House operators’ logs,” although MLK and LBJ “meet in person” days earlier “and speak by phone” days later, making Hirschfeld’s boast implausible. The archives confirm that during Hirschfeld’s visit, no same-day call was made in the artist’s presence, though it’s conceivable the president might’ve spoken about MLK. I asked Stern whether a call could’ve happened off the books, unlogged, but her research finds it unlikely. Instead of letting Hirschfeld skate by with a questionable brag, she presents the facts and lands on a deeper point. Memory, in its capacity to construct, is a muscle. It gets flexed, used, and misused. Here we have Hirschfeld as self-caricaturist, his sleight of hand turned on his experiences.

Stretching the lines was his skill on the page. Stretching events is a skill not far away (take note, journalists). But it’s one of many lively stories in a page-turner that avidly chronicles how brightly he rendered the world. His adulthood was marked by joy as much as anguish; the flu had killed his younger brother, Milton, in 1919. (Al’s life was bookended by pandemics.) But Al never relented in searching for and sharing joy.

And he did make history. The Federal Aviation Administration’s chief scientist used Hirschfeld’s camouflaged NINAs to test pilots’ perceptual ability to spot hidden targets. Adlai Stevenson invited him on an Army plane to visit King Solomon’s mines on a peace-spreading tour. 14-year-old Al played baseball with 14-year-old Lou Gehrig. And the first caricature stamps in postal history were Hirschfelds (but had to omit NINAs because no stamps can carry “secret marks,” though he slipped them in as signatures anyway).

At each step, Hirschfeld flirted with the powerful but remained skeptical of power. He never cozied up for careerism. Just the opposite, he joined the fight against fascism and censorship in the ’30s and ’40s by turning out anti-Nazi cartoons. He took aim at senators and status-quo gatekeepers and hate-spewing radio hosts. And he advanced discussions of racial representation in newsrooms by submitting diverse work even when those newsrooms weren’t. Time commissioned him in 1998 to draw five century-defining artists. He rightly included Louis Armstrong. This prompted a debate among editors about the difference between true diversity and performative gestures of inclusion for institutional appearance. It’s all on pages 314 through 316 of the biography, endlessly insightful.

What I value most in this study is less its granular detail than the vanishing line it traces between how caricature conceals and reveals; the role of artists and reporters in clarifying or obscuring. How many in the media still engage in caricature? For good or ill? How many of us use caricature to get at essence?

There are many Ninas to find in Hirschfeld’s drawings. And just as many Als in Stern’s biography. He hides, like those he drew in his 99 years, in plain sight.